On October 21, 1914, Mewa Singh walked into Vancouver’s courthouse and shot William Hopkinson, an immigration inspector whose work involved uncovering and undermining anti-colonial organizing in the local South Asian community. Three months later, Singh was hanged for the murder in New Westminster.

Singh is celebrated as a martyr by Sikhs, but he’s largely unknown outside the South Asian community. In the last few years, community organizers have been trying to change this, calling for Singh to be commemorated and officially exonerated. Although calls for his exoneration have so far been unsuccessful, in 2020 the city of New Westminster responded to community efforts, declaring January 11 “Mewa Singh Day” and releasing a proclamation that describes him as a “humanitarian” who “[fought] against racism.”

Although the proclamation records that Singh was executed in New Westminster, it doesn’t mention why he was executed – an omission that reflects the tensions inherent in asking the government to memorialize someone who took up arms against the state.

The New Westminster declaration seems to represent a variation on the tradition of mainstream responses to Singh, rather than a break with it: for Mewa Singh to be celebrated, his story must be rewritten.

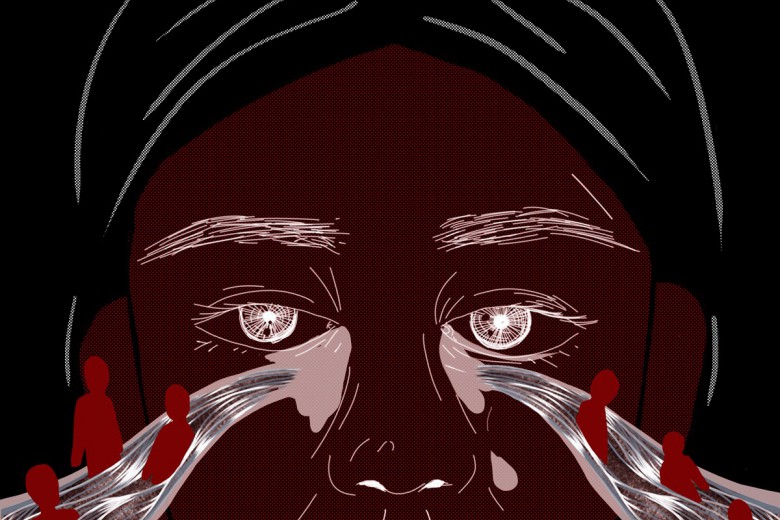

Does official commemoration of Mewa Singh come at the cost of turning him into someone else – turning his act of violence into the more palatable “fight against racism”?

Hopkinson’s racism wasn’t just his own – it was that of the state. The immigration inspector made himself an enemy of the Sikh community (and especially members of the Ghadar Party, who sought to overthrow British colonialism in India) through his commitment to mainstream government policy. In addition to working to prevent the landing of the passengers of the Komagata Maru in 1914, Hopkinson was an enthusiastic participant in what sociologist Bonar Buffam has called “the elaborate webs of racial and colonial intelligence gathering” between Canada, the U.S., England, and India.

Immediately after killing Hopkinson, Singh surrendered to the police. He pleaded guilty to murder, and waived the right to have his trial translated into Punjabi. But he did want to explain his actions to the courtroom packed with white Vancouverites. (As one contemporary newspaper reported, “Not a single Sikh was admitted to the courthouse, all being turned away at the door.”)

Singh explained that he killed Hopkinson because he, like many others in the Sikh community, blamed the immigration official for a mass shooting. A few weeks earlier, one of Hopkinson’s informants had opened fire at the Vancouver gurdwara (Sikh temple) while Singh was performing kirtan (prayers). Two men were killed, and several others wounded.

Inside the Vancouver gurdwara where Hopkinson’s informant killed two Sikh men. Photo by Yucho Chow, courtesy of the Sarjeet Singh Jagpal Collection.

“There are no words in my language to express the sorrow and troubles and worries I have had to put up with in Vancouver,” Singh told the audience. He described the Sikh community’s sense of being “walked on,” extorted, and ignored by Canadian governments and law enforcement.

Recounting his experience of the mass shooting, as well as other examples of Hopkinson’s harassment, Singh explained that he killed Hopkinson “out of honour and principle to my fellow men and for my religion,” “in the cause of justice,” and to help the Sikh community: “I have taken Mr. Hopkinson’s life and am going to give my own.”

Singh considered himself to be a shaheed (a martyr) and he has been understood this way by the Sikh community since his hanging in a New Westminster jail yard on the morning of January 11, 1915. After his execution, a procession of hundreds of Sikhs carried his body from the gallows in New Westminster to a lumberyard on the Fraser River, where he was cremated. Sikhs in B.C. continue to celebrate Singh: his portrait appears on the wall of the Ross Street gurdwara in Vancouver, the local Khalsa Diwan society commemorates him annually, and he is remembered in local Vaisakhi parades.

As historian Hugh Johnston notes, in 1914, “the white majority in Vancouver saw [Hopkinson] as the hero.”

Since Singh shot Hopkinson, there’s been little evidence to suggest that Canadians invested in the state (and its monopoly on violence) are willing to understand Singh on his own terms, let alone celebrate him.

As historian Hugh Johnston notes, in 1914, “the white majority in Vancouver saw [Hopkinson] as the hero.” Two thousand people, including Canadian and American government officials and police, took part in Hopkinson’s funeral procession; newspaper coverage described him as “the man who had laid down his life for the maintenance of law and order.” Conservative Member of Parliament H. H. Stevens wrote to Prime Minister Robert Borden, advising Borden to direct officers to “arrest and deport” all of the men associated with the gurdwara. While Borden didn’t take his advice, Stevens would not have been alone in seeing Singh’s decision to kill Hopkinson as justification for B.C.’s white supremacist legal system, rather than a principled rejection of it.

A few decades later, anthropologist Verne A. Dusenberry found that Punjabi Sikhs in and around Vancouver continued to venerate Singh as a martyr. On the other hand, Gora Sikhs – white followers of a sect of Sikhism founded by Harbhajan Singh Khalsa – “preferred to celebrate the more socially and temporally distant and morally unequivocal heroic martyrdoms of the Sikh gurus.” The gurus, having lived and died hundreds of years and thousands of kilometers away, had no need to take up arms against colonial law enforcement.

The exterior of the gurdwara, on 1866 West 2nd Avenue. Photo from the City of Vancouver archives.

The New Westminster declaration seems to represent a variation on the tradition of mainstream responses to Singh, rather than a break with it: for Mewa Singh to be celebrated, his story must be rewritten.

In describing him as a “strong advocate” who “died fighting against racism and for the dignity of the Sikhs and all South Asian immigrants,” the declaration leaves out Singh’s religious motivation for killing Hopkinson. There are forms of violence that are forbidden to Sikhs, and – as the veneration of Singh and other martyrs indicates – forms of violence that can be understood as a religious obligation. The Sikh duty to defend the Khalsa (nation or community of Sikhs) is represented by the kirpan (symbolic dagger) worn by baptised Sikhs and by the weapons displayed in gurdwaras.

In his statement to the court, Singh reminded his audience that Christians aren’t the only ones with a tradition of martyrdom, in which the death of an individual is preferable to the death of the community: “You, as Christians, would you think there was any more good left in your church if you saw people shot down in it [?]” He continued, "You could not put up with it, because it would be bringing yourselves to a nation which is dead, to tolerate such conduct. It is better for a Sikh to die than to bring such disgrace and ill-treatment in the temple. It is far better to die than to live.”

More than a century after Singh’s execution, it’s become easier to publicly celebrate anti-racist activism, especially in the abstract.

The jury deliberated for less than ten minutes before returning with a guilty verdict. There’s little evidence that those who heard his speech firsthand were willing to take his argument seriously – perhaps because they saw Singh (correctly) as a threat to white supremacist Canada.

In 1914 and today, racialized communities in Canada and elsewhere are under pressure to refrain from forms of organizing and resistance that threaten – or seem to threaten – the maintenance of the status quo. As Loveleen Kaur points out, representations of Sikh men as violent terrorists reflect traditions that date back to British imperialism in India: “The imagery of the Sikh extremist used in contemporary times is similar to that which was applied to the Ghadar Party in Canada by both the Canadian government and the British raj.”

More than a century after Singh’s execution, it’s become easier to publicly celebrate anti-racist activism, especially in the abstract. It remains to be seen whether the calls for Singh's exoneration will ultimately meet with success, but it’s hard to envision broad public celebration of an anti-colonialism that is neither non-violent nor secular – one that rejects, like Singh did, both white supremacy and the state’s monopoly on violence.