The last time Dora Morris saw Jethro [Anderson], he was with her son Nathan, who was two years older than her nephew. Dora, a tiny woman with a mighty heart, was not only Jethro’s aunt, sister to his father, Sam; she was also Jethro’s guardian, his boarding parent, his second mom. Dora was a mother figure to all the kids in the neighbourhood, who often congregated at the happy, two-storey home she shared with her husband, Tom Morris, in the Fort William end of [Thunder Bay]. Dora was from Kasabonika Lake First Nation and Tom from Kitchenuhmaykoosib Inninuwug (Big Trout Lake) First Nation. Their descendants followed the animals and travelled when the seasons changed, settling high up in the northernmost region of Ontario. Human bones found on the shores of Big Trout Lake date back nearly 7,000 years, proving people had occupied this harsh and remote part of the world far earlier than the time of first contact with Europeans.

Dora’s mind was spinning in circles on that first, awful, long night. She felt every tick of the clock as she waited for her nephew to walk through the door. As soon as the sun began to rise, Dora couldn’t wait any longer. She picked up the phone to try to get a hold of Stella [Jethro’s mother].

She choked out the words. Speaking them made it harder — it made them true: “Jethro didn’t come home last night.”

The last time Dora saw Jethro, it was a Saturday afternoon. The boys were at home, anxious to go to the mall.

Dora’s mind was spinning in circles on that first, awful, long night. She felt every tick of the clock as she waited for her nephew to walk through the door.

Nathan and Jethro had always been close. They had spent countless hours in the bush, climbing trees and using their slingshots to snag partridges for supper. Both spoke Oji-Cree until they were adolescents and moved to Thunder Bay where they shared a room, played video games, and hung out in comfortable silence on the couch.

Before Dora left for work at the Wequedong Lodge, a housing service for people travelling from remote First Nations into Thunder Bay for medical care, she gave the boys $2.50 each to buy a pop or a snack and told them to be home later for dinner. She told Nathan that he was in charge while she and Tom were out. Tom was an executive at Wasaya Airways, an Indigenous-run airline that services the remote communities in the North. When he went on a business trip, it usually involved an 800 kilometre round trip on a puddle jumper plane.

Seventeen-year-old Nathan often looked after his younger siblings — Adrienne, who was 12, and David, who was 15. Dora knew he was responsible, and that he and Jethro wouldn’t blow their 10 p.m. curfew.

When the boys left she went upstairs to get ready for work. Dora had been hired by the lodge to help the many elderly patients who didn’t speak English well or had lost the ability to communicate in the settlers’ language to time and dementia. She spent her days translating from Oji-Cree to English, so the caregivers could understand what the patients needed. Even at work, Dora was always busy caring for someone.

When she went on break at 9 p.m., she called home to see how the kids were doing. Nathan, David, and Adrienne were at home with their friends, but Nathan told her that he had separated from Jethro hours earlier and that Jethro hadn’t made it home yet. She thought this was strange and she began to worry.

When Dora got home from work at 11 p.m., she met Tom, who was just returning from another business trip, in the driveway. When they walked through the door, their kids were hanging out in the family room with their friends.

Dora instantly saw that Jethro wasn’t there. She looked at Nathan and he told her Jethro still wasn’t home.

Nathan confessed to Dora that they hadn’t gone to the mall like he had told her. Instead, they went to their cousin Leeanne’s house to drink. Earlier that morning, Nathan had dropped off some beer, which he had gotten from a runner. In Thunder Bay, a “runner” is an adult over the drinking age of 19 who buys alcohol for underage kids in exchange for a tip or some booze.

Nathan and Jethro had hung out that afternoon with Leeanne, her boyfriend Chris, her sister Debbie, and Starlight Frogg. Nathan didn’t stay long. He had promised a girl he was seeing that he would go visit her at the Intercity mall where she worked. He left Jethro at the house and headed for the bus stop.

Nathan would see Jethro once more that day, through the window of the bus. His cousin was walking down the street. He could have been headed to the corner store. He could have been going to the mall or to another friend’s house. Nathan didn’t know. All he knew was that Jethro looked happy.

Dora hid her rising fear from her kids. She and Tom told them not to worry; they were sure Jethro would be home soon. Just in case, she asked Nathan to go out and check with his friends at their usual haunts, to see if anyone knew where Jethro was.

While Nathan was out, Dora and Tom got into their van and drove up and down the residential streets — Victoria Avenue, Vickers Street, Balmoral, and Red River Road. Dora scanned all the doorways and the driveways, and looked down the sidewalks. They also cruised the Arthur Street strip.

After four hours, they went back home; it was 3 a.m. Nathan was there and reported that none of his friends had seen Jethro. Fitful, exhausted panic came creeping in. Dora spent the next few hours waiting, but to no avail. She decided to call the police.

“My nephew hasn’t come home,” she said.

“He’s just out there partying like every other Native kid,” the officer said. Then he hung up.

Shocked, Dora put down the phone. His comment felt like a slap in the face.

Dora began to make more calls.

The first was to Stella, who was more calm and measured. She believed her son would be home soon.

Next, Dora tried to find Sam, Jethro’s dad, in Kasabonika. He didn’t have a phone, so she called other relatives, looking for him. She thought about calling her own father and then stopped herself. She didn’t want to alarm him in case Jethro suddenly walked through the door. She called the police again, who said it was too early to file a missing persons report. Jethro had to have been gone for at least 24 hours.

When the sun came up, Dora and her husband went back out. Daylight was a blessing. One of Adrienne’s friends had told her the night before that a lot of the kids hung out at the [Kaministiquia River] waterfront by the underpass and the tugboat, where they could drink. It was the first that Dora had heard that going to the river to drink was a popular thing to do among the teens.

Dora and Tom picked up Adrienne’s friend and drove down to the river. After the girl showed them the underpass, they drove her home and went back to search the area. There was no one there at that early hour. Clearing away the long grass and brush, they poked through litter and twigs, looking for any sign of Jethro.

Nathan also went back out, canvassing the kids he met on the street. He got lucky. Somebody told him that Jethro was seen at the Brodie Street bus terminal, but that he stayed for only a short time before heading down to the river. The bus terminal was another popular meeting place for many of the students who didn’t have cars and travelled everywhere by bus.

When Dora got back to the house, Nathan told her what he had learned. She called the police again, asking if there were any leads. Her queries were met with silence. She was told again that maybe he’d be home later. When the party was over.

She called the police again, asking if there were any leads. Her queries were met with silence. She was told again that maybe he’d be home later. When the party was over.

At 8:20 p.m., on Sunday, October 29, [2000,] Dora walked through the doors of the Thunder Bay Police station and filed a missing persons report.

From that first night on, Dora and Tom never stopped searching for Jethro.

A few days after her son went missing, Stella arrived from Kasabonika along with her family and other members of the community. Volunteers in Thunder Bay were also recruited to help search for Jethro. Among those who answered the call were Alvin Fiddler and his wife Tesa. They joined the teams of searchers – practically all were Indigenous – as they combed the Kam’s banks, looking for any signs of the boy. The Fiddlers had just moved to Thunder Bay and Alvin had taken a job as the health coordinator for Nishnawbe Aski Nation. Tesa insisted on searching even though she had their newborn adopted daughter, Lynette, with her. Everyone hoped that Jethro would be found safe, but as time passed the reality of the boy’s disappearance from the brand-new high school was setting in. It seemed everyone was out looking for Jethro – everyone but the police.

“They didn’t even put up a notice in the media until a week after. It was November 5. I still have the news clipping,” Dora said.

Police did not start a missing persons investigation until six days after Jethro’s disappearance.

Dora continued to call the police to check on any leads, and each time she was treated like a nuisance. “Right away, every time I called there, I got used to somebody answer[ing] the phone and hearing, ‘There are no leads,’ or other comments like, ‘He is just out there partying.’”

By that time, Dora was an emotional wreck. “I wasn’t eating. I was puking out all food. I was physically sick.”

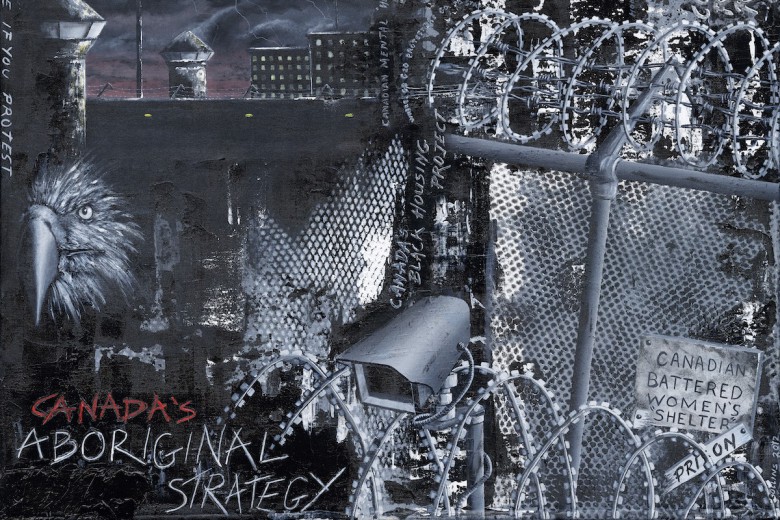

Dora’s experience with the Thunder Bay Police was not unusual. Decades before Jethro’s disappearance and even a decade after, Indigenous people have complained that the Thunder Bay Police did not take their calls seriously. Family members felt they were not given regular updates, and there was little communication with the officers conducting searches or investigating cases of missing persons or victims of murder.

Dora’s experience with the Thunder Bay Police was not unusual. Decades before Jethro’s disappearance and even a decade after, Indigenous people have complained that the Thunder Bay Police did not take their calls seriously.

This was particularly felt by the families of the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG), whose disappearances and deaths some say are far greater than the RCMP’s statistic of 1,181 from 1980 to 2012. The deaths and disappearances of Indigenous women is Canada’s hidden shame. For the longest time, it seemed as though the only group raising alarms about generations of women disappearing was the Native Women’s Association of Canada – a national organization created to fight for the betterment of the lives of Indigenous women. [Only after] the discovery of the gruesome horror of Robert Pickton’s pig farm and his subsequent arrest for the torturous slaying of dozens of women from Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside – he disposed of his victims’ bodies using a meat grinder – did Canadian society begin to pay attention to the stark reality that Indigenous women are being murdered and maimed at a rate several times higher than non-Indigenous women. Then the beaten, bludgeoned, and sexually assaulted body of 15-year-old Tina Fontaine was found floating in Winnipeg’s Red River in the summer of [2014], and the issue exploded when national media woke up to what Indigenous communities had known for years: someone was stealing our women.

In 2014, the RCMP released its first report strictly focused on Indigenous women and girls, culled from officers’ notes and solve rates from across the country. The RCMP claimed that about 90 per cent of the murder cases were solved and that, in most cases, Indigenous women knew their killers. But those numbers never sat well with the Indigenous community, who for decades had been fighting to get some police attention to the national tragedy.

The number of MMIWG seemed too low and the solve rate absurdly high. Many Indigenous families say the killers of their family members remain unknown and they are probably right – the RCMP got their 90 per cent solve rate by asking their officers if an arrest had been made, or was intended to be made, which is what accounted for the number. The RCMP report did not look at convictions or the outcomes of the court cases. They didn’t have the capacity or infrastructure to follow each and every murder case through the court system and record the outcome.

The 1,181 MMIWG number is also in question since not every murdered or missing Indigenous woman was identified as Indigenous by the police. Not every Indigenous person holds a status card. Families also felt some disappearances were not recorded properly and were classified as runaways instead, and that in many cases the possibility of murder was overlooked by police who assumed death was accidental and not a homicide.

In 2015, the Toronto Star took a closer look at the national RCMP numbers and asked the force for all their analyses and sources. The RCMP refused, so the Star – five reporters, Jim Rankin, David Bruser, Joanna Smith, Jennifer Wells, and I; librarians Astrid Lang and Rick Snjzdar; and data analyst Andy Bailey – spent a year and a half making its own list from news reports and court documents. The Star’s numbers differed from the RCMP’s findings. The Star found 1,126 cases of MMIWG, with 936 of those from 1980 to 2015. However, the Star could not gain access to official RCMP data so case counts differed. Overall, the newspaper found 766 murder cases, of which 20 were identified as murder-suicides. Of the murders, 224 were unsolved. The Star found 170 missing Indigenous women and girls, which was comparable to the RCMP number of 164.

The Star’s solve rate numbers, however, were significantly different from the RCMP’s. Between 1980 and 2012, the solve rate compiled by the Star was 70 per cent, lower than the 88 per cent solve rate the RCMP reported in 2014 for the same time frame. Another difference was the unsolved cases. The Star analysis found 180 unsolved cases between 1980 and 2012, while the RCMP cited 120 cases for the same period.

Looking specifically at the Thunder Bay area, the Star found that of all the MMIWG cases from the 1960s to 2014, 54 Indigenous women had been murdered or gone missing in the area. Of those, police had solved 23 cases.

The communication issues with police have existed for years in Thunder Bay and throughout northwestern Ontario. The uneasy relationship goes back decades, back to when the police helped to scoop up kids to send them to residential school, and continues to this very day.

One week after Jethro’s disappearance, Dora got a call asking her to come down to Dennis Franklin [Cromarty, (DFC), Jethro’s school]. Police had set up a command post in the school parking lot. They had found a pair of black lace-up boots by the shoreline and wanted Dora to see if they were Jethro’s. She left her house immediately.

When she arrived at the command post, her heart was racing. Police showed her the boots. They weren’t Jethro’s. They asked if she was sure: the boots were found, tied together, down by the river. She said she was certain and then left, thinking that maybe her nephew was still out there.

About a week later, someone from DFC phoned Dora and asked her to come down to the school again. Once again, she steeled her nerves. She remembered walking into a room full of people. There was one, maybe two officers. She had no idea who the others in the room were, but figured they were with the school. She made a beeline for the brown paper bag the police had. Inside was a black cap with the brand FUBU written across it in giant letters.

She knew right away it was Jethro’s.

Police asked her if she was certain. They told her that this type of cap was sold in lots of sports stores around town. Everybody had one.

She told them again, without a doubt, that the hat was Jethro’s.

She closed the paper bag and pushed it away.

Then she ran out the door.

Dora was a mess when she got in her van. Her mind was racing. She was hysterical and spilling tears of anger.

She started to drive. But this time, she wasn’t combing the streets looking for Jethro. This time, she drove to the highway, put her foot on the gas, and headed straight out of town.

She went north, toward Gull Bay, and was gone for three hours, maybe more, crying her heart out. When she arrived back in the city, she went straight to see Ron Kanutski, her son’s counsellor.

When she got to his office, she saw he was on the phone.

He looked up, startled. He was trying to phone her.

He asked Dora if it was her nephew Jethro that was missing. He had just read about it in the newspaper, which was open on his desk.

Dora cried. She told Ron everything. She told him what had happened, how she had been looking for Jethro, how his hat had been found. She said no one had believed her when he first went missing. She begged Ron to help. She wanted him to get the police to start dragging the river.

She had a feeling. She knew that Jethro was in the water.

It is not easy to drag a river. And the Kam is a cold, swift snake. Boats with large poles attached to hooks motor oh so slowly on the water, fighting its force.

It is not easy to drag a river. And the Kam is a cold, swift snake. Boats with large poles attached to hooks motor oh so slowly on the water, fighting its force.

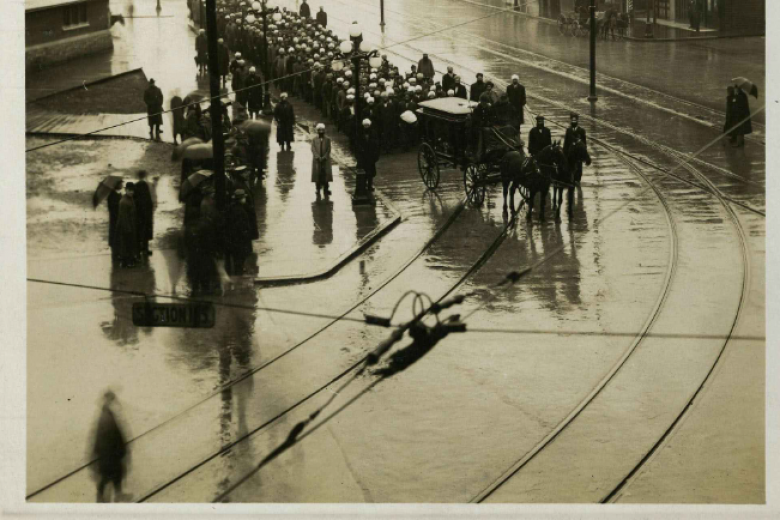

On Friday, November 10, a team from Kasabonika was organized to search the river and police came with their boats.

Dora went down to the Kam the next morning, Saturday, November 11, Remembrance Day. She spoke to some of the Indigenous searchers, who told her they were coming up empty. The river was cold and unforgiving, and they were thinking about stopping for the day.

She begged them not to. She had a feeling. She asked them to persevere and finish out the day.

As the police and the search team continued to scour the water, Dora went home and waited. In the early evening, someone from DFC asked her to come down to the auditorium for an emergency meeting.

She told her children she was going down to the school, that there was a break in the case. Elation broke out among the children. They thought Jethro had been found. Their cousin was coming home. But Dora knew better. She told them to stay home and wait. She muted their excitement, told them not to get their hopes up.

Dora remembers heading to the DFC auditorium and walking through the big steel doors. The gym was packed.

Students, searchers, community members, family, everyone was there.

Dora can’t remember who broke the news. She just remembers the gym erupting into chaos. The crying, the moaning, the screaming swirled around her.

Jethro’s body had been recovered from the river.

It is important to know this: Dora never received a call from the Thunder Bay Police informing her that Jethro’s body had been found.

Dora had filed the missing persons report. She had called the force multiple times, asking to speak to someone, wondering if they had any leads. She had begged them to get in the fishing boat, get out the long hooks, and drag the bottom of the river.

She was never given the common courtesy of a phone call. Not from Thunder Bay Police or the Thunder Bay coroner’s office, who retrieved the body from the funeral home and performed the autopsy.

Excerpted from Seven Fallen Feathers: Racism, Death, and Hard Truths in a Northern City, by Tanya Talaga (House of Anansi Press, 2017).