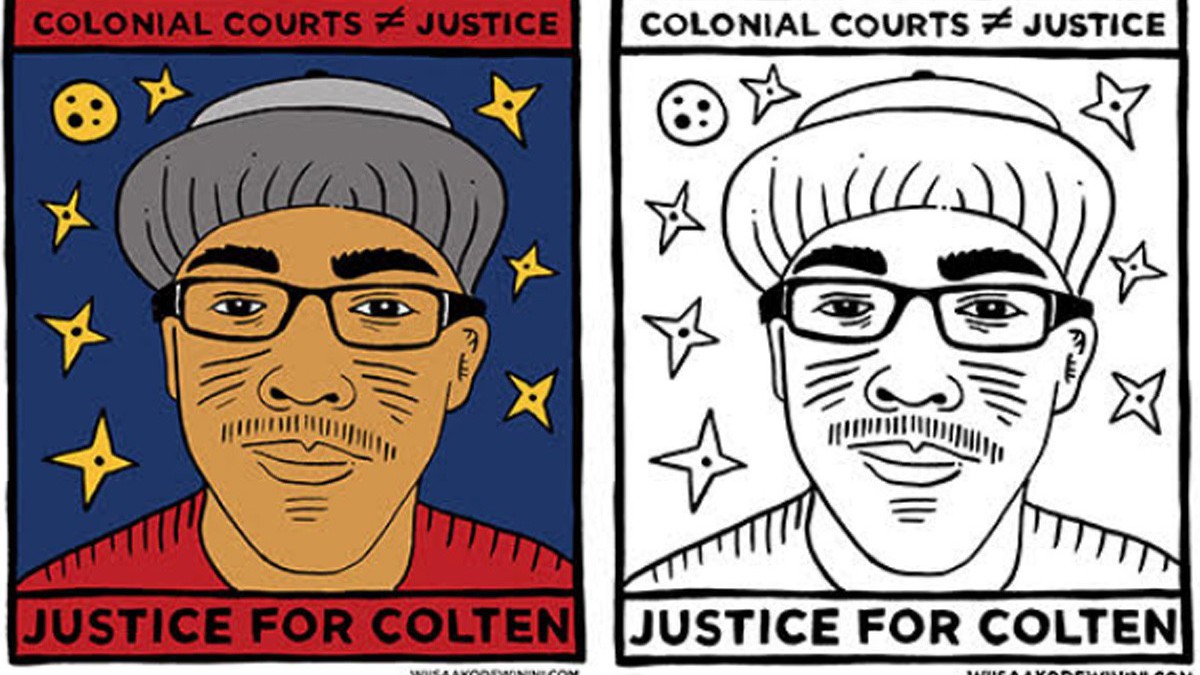

In the wake of Gerald Stanley’s acquittal for the killing of Colten Boushie, I’ve been struggling with a mix of anger, sadness, anxiety, and hopelessness. It’s juxtaposed with bittersweet pride and inspiration from the tremendous outpouring of solidarity from those calling for justice for Colten.

Colten Boushie did not deserve to die a violent death. That is the bottom line. Regardless of all of the versions of events that emerged – in the court room, in Twitter threads, in private Facebook groups – Colten did not deserve to die a violent death. Period. The verdict in the Gerald Stanley trial does not support this. In fact, it sends a message that Colten’s death was warranted, that we should be sorry for the perpetrator, and that ultimately Colten got what he deserved. I find myself at a loss for how to respond to such a sick expression of pure apathy for human life.

What I do know is that Gerald Stanley’s supporters are known racists, who came out from the beginning of this case casting comments like, “the only good Indian is a dead Indian” or that Stanley’s “only mistake was leaving witnesses.” The Indigenous community responded by pointing out the historical and deeply entrenched racism that exists in the province and the country at large.

I want to say I am surprised by the outcome of the case, but I am not. I grew up Indigenous in Saskatchewan, living in Regina and on the Peepeekisis First Nation. Like many Saskatchewanians I spent a great deal of my time driving the rural backroads with friends and family. My family’s traditional territory and trapline was located in Northern Saskatchewan near Uranium City, where my family lived for many generations. Like so many other Indigenous peoples, my family was dispossessed of our lands for industrial development, in our case uranium. Our rights, like our connections to the land, have been so easily taken from us to support the status quo of white settler society.

Once, when I was about seven years old, my family was having car troubles and I suggested we go to the farmhouse that I could see within walking distance. My mother replied, “They won’t help us. They are more likely to shoot at us because we are Indians than help us.” I remember not wanting to believe my mother. Why would anyone assume that a single mother with three small children was a threat? That was over 30 years ago, and clearly, not much has changed.

As I grew older, I came to learn that my mother’s warning was warranted. The colour of my skin and the sounds of my voice quickly became an indicator of how I would be treated. I learned to shed my ‘rez’ accent and find ways to disprove all of the stereotypes I heard growing up: “Indians are all drunks”; “Indians don’t know how to take care of their children”; “All Indians live on welfare.” This is the Saskatchewan that I know, that I’ve navigated all my life. The same one that acquits a white man for murdering an Indigenous man and celebrates this crime with accolades and almost 200,000 dollars in support on GoFundMe.

While I may no longer be a seven-year-old, stranded at the side of the road with my family and fearful of asking for help from white famers, I am still living in a world that devalues Indigenous peoples, our rights, our knowledge, and our systems.

Before someone pipes up – yes, things are changing and moving toward justice. I can remember the apology in 2007, and crying next to Elders who had thought they would never hear an apology for – let alone recognition of – what they experienced. I remember when the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was established in 2008 to bring the historical violence against Indigenous people into public consciousness. I remember when Trudeau was elected in 2015 and made bold promises to reset Canada’s relationship with its Indigenous peoples. And most recently, I remember when Bill C-262, on ensuring that Canada’s laws are in harmony with the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), passed the second reading in the House of Commons on its way to becoming law. All of this is potentially paving the way for finally seeing us as dignified Peoples, rather than a sore on the ‘Canadian’ landscape. But justice isn’t served via lip service, but rather by tangible action.

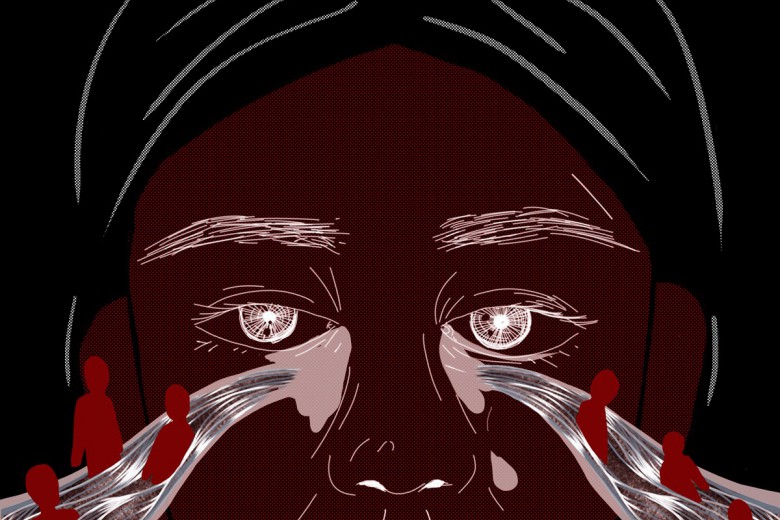

It’s 2018, and Indigenous peoples are still more likely to die a violent death than any other group of people in this country. We have a failing inquiry into Murdered and Missing Indigenous Women and Girls; a child welfare system that has been deemed a humanitarian crisis hundreds of unresolved specific land claims against the federal government for breaches of treaty rights and obligations; and a land regulation system that continues to undermine and dispossess Indigenous peoples of our lands and territories for resource extraction. Couple these realities with inadequate funding for all essential services on reserves and we start to understand that our legal and judicial systems were created to benefit settlers and extinguish Indigenous peoples from the landscape, and ultimately from the consciousness of white society.

The scars are deep in our communities, in the collective community. White settler society needs to stand with us in order to demand the necessary change. It won’t come from a race war, painting the other as the reason for our fear or hatred. It will come when we can see the injustices together and we work toward true Truth and Reconciliation, one rooted in decolonization. Decolonization is, in its simplest terms, a return of and connection to the land.

As an Indigenous climate justice advocate, this case might seem outside of the realm of my work, but it hits so close to home. Whether it’s through the destruction of Mother Earth for fossil fuels and other resources, exacerbating climate change, or justifying the murder of a young man, white supremacy works by detaching humanity from our role in the sacredness of life on this planet. We are out of balance, in the atmosphere, on the lands, and ultimately in our own hearts and minds.

So, as the calls ring out for justice for Colten in the streets, on social media, in the news, and in the courts, remember justice isn’t about one individual – it’s about all of us.