The author owes a debt to Gita Madan, whose thesis, Policing in Schools: Race-ing the Conversation, lays the groundwork for this analysis.

On May 23, 2007, just days after his 15th birthday, Jordan Manners was shot and killed in his high school in northwest Toronto. As the first-ever killing of a student in a school in the history of the Toronto District School Board (TDSB), Manners’ death sparked concerns about the safety of Toronto’s schools and the risk of gun violence.

At the time of Manners’ shooting, the Ontario government was seven years into implementing the Safe Schools Act, which took a “zero-tolerance” approach to disciplining “bad behaviour” in schools. The legislation gave teachers and principals significant power to suspend and expel students. In that time, the rate of police involvement in schools increased, as did suspensions and incidents of teachers’ discrimination against Black students and those with disabilities. Data collected by the Ministry of Education showed that in 2000–2001, prior to the implementation of the Safe Schools Act, 113,778 students in Ontario had been suspended; by 2003–2004, that number had jumped to 152,626 – a total of 7.2 per cent of all Ontario students. The spike in discipline was so sharp that in July 2005, the Ontario Human Rights Commission (OHRC) initiated a complaint against the TDSB, alleging that the measures had a disproportional impact on racialized students and students with disabilities. The OHRC reached a settlement with the board in November 2005: the TDSB agreed to collect and analyze data on suspensions and expulsions to determine the extent of the negative effects of the Safe Schools legislation on students.

When Manners was shot, with the Safe Schools Act in full effect, the TDSB hired lawyer Julian Falconer to lead the School Community Safety Advisory Panel on assessing “school safety.”

The Falconer panel attributed violence and animosity in schools to inadequate social supports in schools and the widespread distrust of school administration, arguing, “schools inevitably mirror the communities that they serve.” It called for increased financial support for school programming and dismantling the one-size-fits-all approach to discipline that the Safe Schools Act had implemented. The panel did not entirely eschew discipline and enforcement, but instead positioned them as components of a larger strategy focused on highly centralized school governance. It advised that community consultation, education, training for students and teachers, and annual reviews of policies were required. The desired outcome was not good schools but more orderly schools.

The community organization Education Action: Toronto (EA:TO) thoroughly critiqued the Falconer report, situating the panel’s recommendations in the rise of outcomes-based education (standardized testing, official profiling, ministry micromanaging) in Ontario: “these government policies are policies on which Falconer remains silent, and yet they are education’s most destructive factors in alienating students and teachers in poor neighbourhoods.” EA: TO describes the recommendations as a shift from “a Tory to a Liberal ‘culture’ of control” – a critique epitomized by the panel’s call to replace German shepherds in school searches with lightweight, “non-threatening” springer spaniels. The Falconer report merely softened the blow in this milieu of sustained securitization.

The TDSB ignored the most fundamental of Falconer’s recommendations – to avoid wholesale reliance on discipline and enforcement – and instead pursued a cheaper option proposed by then-Toronto police chief Bill Blair (now parliamentary secretary to the minister of justice): implementing a student resource officer (SRO) program. According to Public Service Canada, in 2008, aided by a one-year provincial grant of $2.1 million, the Toronto Police Service (TPS) deployed 30 police officers for 30 schools overseen by the public and Catholic school boards; the boards, not the police service, determined which schools would be assigned an SRO. The program signalled a massive escalation in the school securitization process that had begun more than a decade earlier.

Toronto’s first permanent SROs were stationed primarily in “priority areas”: neighbourhoods that the City of Toronto categorized as having high “social risk” in part because of their large numbers of immigrant, racialized, and lone-parent populations. According to the TPS, SROs “work in partnership with students, teachers, school administrators, school board officials, parents, other police officers, and the community to establish and maintain a healthy and safe school community.” TPS records indicate that during the 2015–16 school year, there were 38 SROs (high schools), 19 community school liaison officers (elementary schools), and 11 “School Watch”/high school liaison officers. The deployment of SROs has only broadened the scope of the surveillance of marginalized youth.

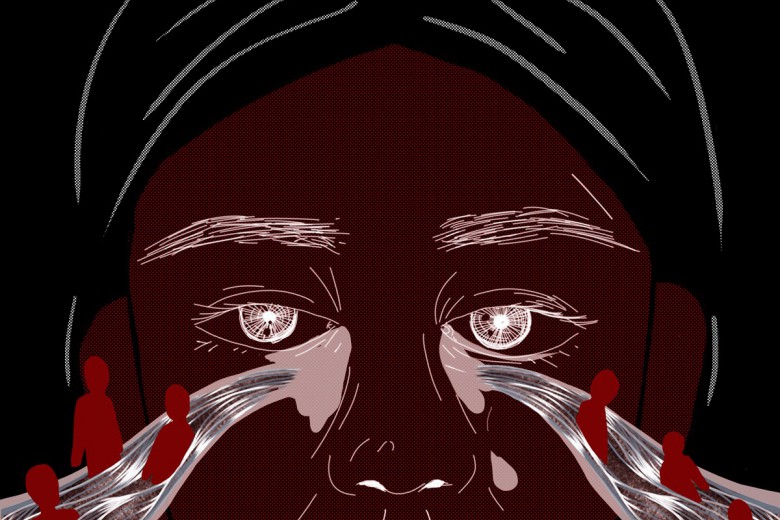

Researcher Gita Madan observes that the conspicuous presence of police in schools results in “a culture of control that constantly codes the bodies of racialized students in particular ways, teaching students about themselves and their place within the hierarchy of the school. It also sends a clear message to the broader school community about the students who attend the school.”

“For example,” she says, “at one school located on a major street, the SRO often insists on parking his police car directly in front of the school instead of in his assigned spot in the parking lot behind the building. This move has resulted in passersby frequently asking what just happened at the school.” Inside schools, surveillance cameras and hall monitors enforcing strict codes of conduct remind students that they are always being watched.

The presence of SROs has created an environment of police saturation, in which sirens, cruisers, and uniformed bodies conspire to insinuate an absolute need for securitization.

Community Policing

The practice of deploying police officers to schools cannot be separated from the practice of community policing. Mandated by the RCMP in 1989, community policing was designed to build trust between police and communities. Imported partly from the U.S. system of policing and in part from the British policing model established under Robert Peel, the central idea followed Peel’s own dictum: “The police are the public, and the public are the police.” Community policing integrated police into communities, relying on community-based surveillance to inform police.

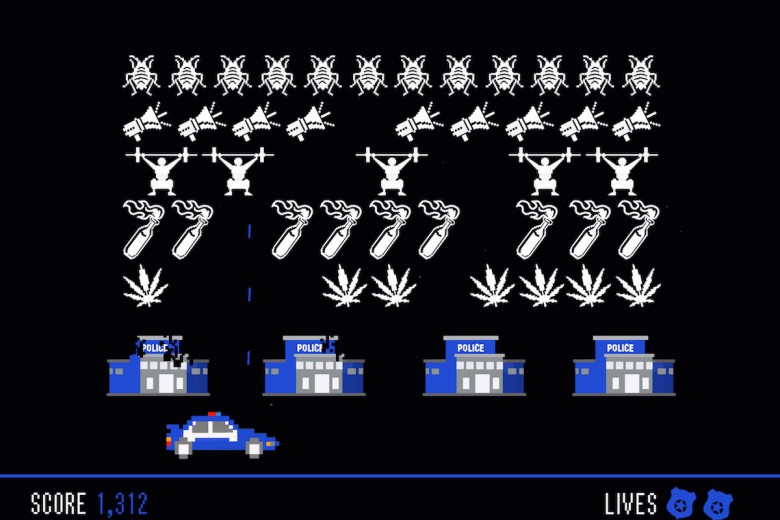

Requiring communities to become responsible for crime and threat prevention permeated not only residential and commercial communities, but also schools. The swell of police violence in the 1960s targeting Black activists in the civil rights movement jump-started the practice of deploying police to schools, ostensibly to improve perceptions of law enforcement. Richard Nixon’s law-and-order campaign, Ronald Reagan’s war on drugs, and Bill Clinton’s war on poverty, in the meantime, vilified young people of colour as the criminals of tomorrow, all the while thinning out the welfare state’s ability to support the working class and adequately fund schools. Following the high-profile school shootings in the U.S. in the 1990s, many American schools adopted programs that rested on the assumption that conspicuous security mechanisms like metal detectors, cameras, and uniformed officers deter violence in schools. On this side of the border, write Abigail Tsionne Salole and Zakaria Abdulle, “some Toronto-area schools are looking increasingly similar to their American counterparts.”

Public Safety Canada explains, “The objectives of the School Resource Officer program are to improve safety (real and perceived) in and around public schools, improve the perception of the police amongst youth in the community and improve the relationship between students and police.” Police services across Canada frame SROs as performing some variation of developing positive attitudes, providing services, and liaising between parents, students, and teachers. In Calgary, for instance, SROs are explicitly marketed as bringing a “visible and positive image of law enforcement.”

But SROs do more than cheerful relationship-building: they have the authority to search, arrest, and charge students, and collect intelligence. In a study of the school-to-prison pipeline for marginalized youth in Canada, Salole and Abdulle recall an incident where students were unable to leave their classroom after a cellphone was reported missing to an SRO. In what amounted to a lockdown lasting over an hour, the SRO fruitlessly searched through students’ belongings. After the students were released, it was discovered that the student who reported the missing cellphone had in fact forgotten it at home.

Since 2011, critical media coverage of the program has disappeared almost entirely, normalizing the increased securitization and regular police presence in schools. Only two evaluations of the program – one in 2009 and the other in 2011 – have taken place in the eight years that police have been stationed in schools. Both evaluations were conducted internally by the TPS, and unsurprisingly, they found that the program and its officers had an overwhelmingly positive impact. As Madan notes, the evaluations were rife with methodological flaws, prioritizing officers’ experiences and perceptions of the program’s effectiveness over the students’, predictably highlighting the positive impacts of the program.

It’s difficult to find current information about Toronto’s SRO program. (I had to leave my contact details to get information when online sources and attempts to contact the school board failed.) Most current information on SROs has been produced and vetted by the TPS corporate communications team, offering “success stories” from police via newsletters, television interviews, and social media. But these “success stories” are uncomfortably situated against the backdrop of 20 years of under-resourcing in Ontario’s education system, a problem felt most acutely by the TDSB, the largest board in the province. While overall education spending has increased since the Mike Harris years (1995–2002), the provincial government continues to draw on the Harris government’s flawed funding formula, which excludes support for physical education, field trips, art classes, and libraries. As a result, the TDSB has been locked in a system of recurring budgetary shortfalls: in 2012, the shortfall was $109 million, increased by $50 million the following year, and rose to $189 million by 2014. To remedy this problem, the TDSB searches for areas where it can find “savings,” cutting the number of elementary and secondary teachers, lunchroom supervisors, and most recently, 50 special education jobs. These cuts work with the increased securitization of schools to create a school environment that is hostile to marginalized youth and unable to adequately respond to their needs.

While research demonstrates that racialized, low-income, and disabled youth face harsher discipline in schools and higher rates of dropping out and incarceration, researchers like Salole and Abdulle note that, “due to data constraints, it’s impossible to determine whether it is the same youth who are ‘pushed out’ of school and subsequently incarcerated.” What is clear, however, is that amid security cameras, random searches, and armed officers, the experience of surveillance, profiling, and brutality that many marginalized youth face outside of school is replicated in schools. The classroom is becoming increasingly indistinguishable from the prison as students made “known to police” on the street through carding may later encounter police in their school.

Several qualitative studies have shown that SROs effectively prime students for the prison system by cultivating fear, mistrust, and alienation – barriers to the pursuit of education and employment. In 2009, a Toronto Star investigation found that schools with the highest suspension rates were also typically in areas with high incarceration costs. The investigation, which combined suspension rates with postal code data for inmates, also noted that school principals frequently circumvented suspension guidelines by imposing unattainable conditions for students to access alternative programming. One Toronto student’s 19-day suspension for smoking marijuana lasted in effect almost five months and required a lawyer’s intervention before he was able to return to school. Discrimination against marginalized students pushes them away from schools and out onto streets that are equally, if not more, hostile to their needs.

Sudden escalations

Madan explains that one way the SROs “build relationships” with students is by inserting themselves into the students’ recreation. “I asked one of my former students how he felt about his junior boys’ baseball team being scheduled to play several games against a team of police officers. He said, ‘I’d rather just play against another school. I don’t wanna shake their hands because they’re the ones who are constantly looking at me every time I’m walking down the street.’”

In an interview with researcher Melanie Willson, a teacher named Adam captured the escalation of response: “There was a fight that broke out in a classroom. And the principal’s office was called and the VP came up and he brought up not only the [SRO], but two of his friends who happened to be visiting him. So the kids [were] ushered down to the office, accompanied by three police officers. And I said to the VP, ‘Do we really need to bring these people for a fight?’ And he’s like, ‘They’re here in the school. They’re here. I use them.’”

In another instance, a TDSB teacher named Darrel recalled that, when an SRO demanded that a student take his hood down, the student responded by saying, “You’re not staff here … who are you to tell me to take my hood off?” The SRO took the student to the ground for being aggressive, a response so disproportionate that it’s reminiscent of police officer Ben Shields violently taking down a 16-year-old Black girl in a classroom in the U.S. This everyday discipline not only obscures the relationship students have with police and administration, but also intimidates poor, racialized students with both the threat and the realization of everyday violence. Students who transgress by fighting and wearing hoodies are reminded that police serve to enforce dominant class rule.

Taken at their word

In an era where cuts to education have become commonplace, the well-padded TPS budget bestows vast time and economic resources to SROs, advancing their status as an indispensable part of the education system. The words school and resource tacked onto the word officer have depoliticized police labour, ignoring the ways that it mobilizes hierarchies of class, race, gender, and ability in the service of oppression.

In 2009, just two years after the death of Jordan Manners, a video of an altercation between a student at Northern Secondary School in Toronto and an SRO, Constable Syed Ali Moosvi, went viral. According to reports, the altercation began after a 16-year-old student called Moosvi “bacon” as he walked through the hall. Moosvi pushed the student against the wall, ordering him to put his hands behind his back. The student repeatedly said that he’d done nothing wrong and did not deserve to be arrested. But Moosvi continued pushing the student against the wall before yelling, “What don’t you understand? Put your hands behind your back!”

“What have I done? Don’t you have to let me know what I’ve done first?” the student asked as he was dragged through the large crowd that had formed. People in the crowd yelled profanities at Moosvi, exclaiming, “We’ve got you on camera!”

TPS spokesperson Constable Wendy Drummond said of the incident, “One of the reasons for the officer to be there is to create a safe atmosphere.” In the end, Moosvi, already once acquitted for assaulting a hearing-impaired Black man, escaped charges. The student, by contrast, was charged with assault with intent to resist arrest and was suspended from his high school. Josh Matlow, a school board trustee, concluded that the incident only reinforced the need for police in schools: “As sad as this incident was, I think this absolutely supports the reason why we need the program. … There’s obviously a gap between students and police and I think both sides have some stereotypes about the other.”

SROs are well-resourced police officers. Perhaps by accurately naming their positions, we can begin to cut through their authority. A police-centred perspective that takes the police at their word will always obscure the experiences of racialized and low-income communities, which should rather be amplified. If schools are to be safe for all students, they must adopt a hard-line, zero-tolerance policy against the police, not marginalized youth. Replacing SROs with support workers, who can assist students without increasing their likelihood of interacting with the prison system, must be the top priority.