In early 2010, the Winnipeg Police Association (WPA) embarked on a campaign to pressure the city to pay cops for daily workouts.

The rationale, as explained to media by then-WPA president Mike Sutherland, was simple: “Our clients are coming out of jail well fed and well muscled” as “every jail in the country now has a workout facility that’s pretty good.” Sutherland argued that upon release, “gang members” continue to train at “martial-arts gyms” – described by the Globe and Mail as teaching UFC-style techniques “to break bones and tenderize faces” – meaning they were only “getting bigger, stronger, faster.”

This reality put cops at a major disadvantage, he claimed: “You can go from a scenario where you’re sitting in a cruiser car or sitting at a desk […] your body’s essentially relaxed, and moments later you could be involved in a fight for your life. It’s rare to have an offender who’d be willing to let you stretch out and warm up.”

This request for 20 to 30 minutes of paid gym time per day was swiftly rebuffed by then-Winnipeg police chief Keith McCaskill due to “taking a lot of resources off the street.” However, the Winnipeg Free Press reported that he acknowledged “officers are dealing with more violent offenders and weapons like firearms on the street” and pointed to the creation of the Tactical Support Team and plans to introduce a police helicopter as ways “the force is trying to protect officers.”

This short-lived push by the WPA for paid workouts may seem like an absurd triviality of recent history. But it was a manifestation of the police union’s broader project of cultivating an atmosphere of paranoia, distrust, and fear as a means of expanding already enormous police funding, resources, and power.

This means that the WPA, and police unions more generally, are far from mere labour organizations concerned with contract negotiations and workplace grievances.

The first article in this series on the WPA, published in the January/February 2021 issue of Briarpatch, examined the police union’s history of systematically protecting its membership from any accountability for killing, assaulting, and harming mostly Indigenous people. To do so, the union used a combination of conventional labour union activities – winning high pay through binding arbitration, protecting members from being sanctioned or fired – alongside the state monopoly on violence and ceaseless “copaganda” efforts. These efforts were mostly focused inward, working to undermine and delegitimize investigations into police violence.

This follow-up article expands on that research by looking at the WPA’s outward-facing and more ideological activities in recent decades. It argues that the WPA deliberately weaponizes a “politics of shock,” in the words of anthropologist Joseph Masco, to shore up continued public support for police response to almost every imaginable situation, not only in the present but – very crucially – for the indefinite future.

This means that the WPA, and police unions more generally, are far from mere labour organizations concerned with contract negotiations and workplace grievances. They are also ideological organizations that actively fight to sow racist and anti-poor hatred as a means of maintaining their funding, impunity, and political influence over the city. In fact, it is because of this ideological work that the WPA maintains such power at the level of negotiations, grievances, and budget fights.

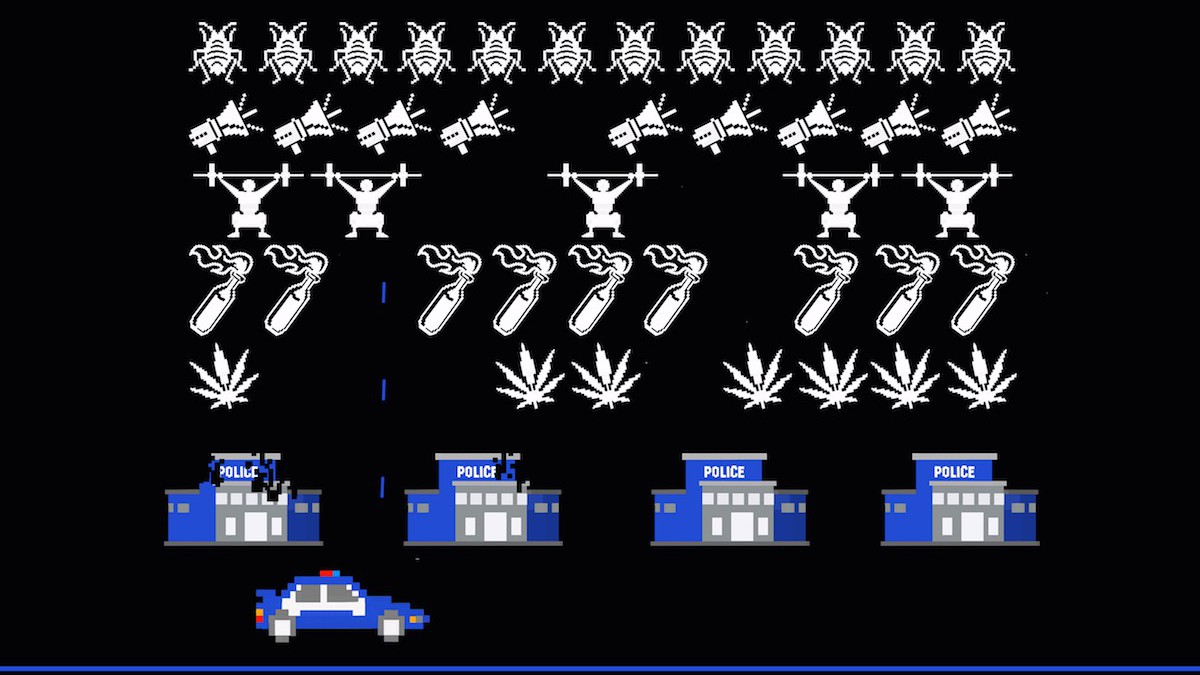

Bugs, drugs, and video games

In a 2022 journal article analyzing the media strategies of police unions in Toronto and Winnipeg, scholars Jamie Duncan and Kevin Walby describe the main story that the media tells: police are “embattled heroes” that are “under attack by policies of austerity on one side and ‘emotional’ social justice advocacy on the other.”

One of the key examples that Duncan and Walby provide of this discourse in Winnipeg is the supposedly constant threats that cops face while leaving downtown headquarters due to a lack of secure staff parking. Following an alleged attempted robbery of an officer in early 2018 near the building, WPA president Moe Sabourin seized on this incident as symptomatic of a larger problem and as proof that police are under attack and need greater protections: “We are in a unique profession and we have the ability to take away peoples’ liberty and there are people who take offence at us and want to get back at us.”

This idea is foundational to police union activities. For the WPA, and all police departments across North America, threats are everywhere. It’s not just the supposed concern over officers getting beat up by MMA-trained gang members while at the gym, or shopping, or walking to their car. In recent years, the police union has complained to the media about officers carrying home bedbugs (due to work in “a lot of sort of rundown environments”), interacting with drugs supposedly contaminated with fentanyl (“our members encounter all sorts of different powders and substances during their duties”), and even the video game Grand Theft Auto being played in a provincial jail (“I’m alarmed that it happened in the first place”).

The spectre of high stress and low morale is constantly invoked to advance this discourse of the “embattled” cop, with the WPA telling media in 2011 that “there’s not only the physical danger, the legal jeopardy, [but] then there’s also the intense public scrutiny and in some cases intense public criticism, in some cases, from the media and in some cases, from people […] without any real level of expertise or understanding.”

That’s the thing about police as “embattled heroes” who harness the “imaginary to locate danger”: the supposed threats to their bodies, psychologies, and time can never decrease, but only ever exponentially multiply.

This also encompasses the supposedly ever-growing demands on the time and attention of cops. Over the years, the WPA has made clear that it doesn’t want its members to have to “babysit” intoxicated youth, write traffic tickets, or be reallocated from specialized divisions to front-line duty. All of these things, the WPA claims, eat up precious time and render police “almost totally reactive” through responding to 911 calls (in contrast to their data-driven “proactive” policing, which is when police surveil geographic “hotspots” and “persons of interest” – think traffic stops and street checks – without an alleged crime having been committed).

It was because of such concerns that a dramatically lower-paid class of “police cadets” was introduced in 2010 and has since been tasked with many of the most undesirable tasks: directing traffic, supervising patients admitted to hospital on mental health grounds (“the cadets were specifically crafted to deal with that issue”), and working in arrest processing (the mundane administrative aftermath of an arrest, including photographing and fingerprinting the arrestee). However, in 2015, WPA president Sabourin noted that despite the development of the cadet program, Winnipeg police response times were still among the worst in Canada: “And quite honestly, they’d probably be worse than what they are now if it wasn’t for the cadets,” he remarked.

That’s the thing about police as “embattled heroes” who harness the “imaginary to locate danger”: the supposed threats to their bodies, psychologies, and time can never decrease, but only ever exponentially multiply.

A permanent war posture

According to police unions, the “embattled” state of police can only be solved through more and more policing. The problem is never seen as inherent to policing but the product of a lack of funding, resources, supports, and powers to conduct that work.

This makes sense at a very material level: as Duncan and Walby note, police unions are “economically incentivized to grow and preserve their paying membership.” But it also requires what Masco describes as a “permanent war posture.” In the parlance of policing, Duncan and Walby write, this includes – but isn’t restricted to – the concept of the “thin blue line” that “frames police as the only boundary between order and violence, while conflating policing with the public good.”

The WPA has advanced a range of “solutions.” One, as the police chief offered in response to the push for paid workouts, is increased militarization via new equipment, units, and weaponry. In 2006, the WPA welcomed the adoption of Tasers as “another tool to deal with the ever-increasing amount of violence officers see out there” and repeated long-standing calls for a SWAT team as “there is an onus on the WPS and citizens to have the best resources available.”

In 2015, Sabourin defended the purchase of a $343,000 armoured personnel carrier – frequently described by critics as a “tank” – because “Winnipeg has a little big-town syndrome” and “we don’t see ourselves as a very dangerous place, but it is very dangerous.” In 2016, when the WPA pushed for the police service to buy carbine rifles for each cruiser, Sabourin framed it as a workplace safety issue due to the need to neutralize long-range threats: “There are so many hunting rifles and different firearms out there that bad guys have access to, and all we have is a shotgun and a service pistol,” he told media.

The WPA has advanced a range of “solutions.” One, as the police chief offered in response to the push for paid workouts, is increased militarization via new equipment, units, and weaponry.

Another aspect of strengthening this “permanent war posture” has been the union’s activist approach to changing or strengthening laws. In 2008, the WPA expressed opposition to a Supreme Court of Canada decision to end “random” drug searches of people in public places like schools and bus stations using sniffer dogs, describing it as “another chink in the armour of policing tools.” Similarly, during the auto theft panic of the late 2000s, the WPA called for the federal government to make auto theft a separate offence (rather than remaining designated as a property crime) and advocated for jail time rather than ankle bracelets for offenders. Then-union president Mike Sutherland also called for a strengthening of the Youth Criminal Justice Act: “If you’ve got a 13, 14, 15, 16-year-old chronic car thief and you have to keep them in jail for three, or four, or five years, then do that.”

Even blatant police ineptitude has been leveraged by the WPA to ask for more funding. For instance, a 1992 trial of three members of the Ku Klux Klan in Manitoba – who were charged with advocating genocide and promoting hatred – was halted because the undercover cop changed her testimony during the trial and admitted to improper tape recording practices. In response, the head of the WPA blamed an inadequate police budget, declaring: “If proper manpower, equipment and training aren’t provided, you’re going to run into problems.”

Near-identical apologia was used during the inquest into the 2000 killings of Métis sisters Corrine McKeown and Doreen Leclair – who called 911 many times prior to their deaths but were repeatedly dismissed by operators as intoxicated and to blame for their situation. The WPA attributed it to a lack of officers and cruisers, remarking that “the thin blue line is too thin.”

Another aspect of strengthening this “permanent war posture” has been the union’s activist approach to changing or strengthening laws.

In 2013, when the city ordered an operational review of police spending, the Canadian Police Association countered it with their own analysis, hoping to undercut the city’s findings. However, both reviews ended up recommending fewer police officers, which the WPA sheepishly claimed illustrated the “unique challenges” the Winnipeg police face.

In 2015, the police helicopter accidentally broadcasted a sexually charged conversation between the flight crew. The humiliating moment was also absurdly framed by the WPA as a potential public safety issue: “What’s concerning is if an external system, and this time it was the PA, could be activated without a warning to the pilot, that’s a question that’s got to be asked, because what happens next time if it’s the system that dumps fuel?”

As Masco observed about the counterterrorist state, “failure and disaster, like surprise and shock, can be absorbed as part of its internal circuit.” At every opportunity, the WPA struggles to solidify this “permanent war posture” built atop of its meticulously curated image of the police officer as an “embattled hero.”

Against a “Mary Poppins approach”

The WPA has always worked to exploit public opinion to advance its aims, including what Duncan and Walby describe as “tactical media interventions” that “work to deepen their influence in local politics while defending a conservative vision of what policing is and should be.”

In recent years, as police violence has led to calls to defund the police, the tendency has grown; rather than only focusing on insulating police officers from accountability for their violence, the WPA has sought to leverage the “embattled” and “permanent war” discourses into political change.

One way the WPA has done this is through support for electoral campaigns. The WPA endorsed Liberal-backed insurance agent Ernie Gilroy in his 1992 run for mayor due to his pledge to spend $1 million on police vacancies if elected. But after that, it remained “politically neutral” for decades: in 2008, the union briefly endorsed Winnipeg cop Shelly Glover’s run as Conservative MP – but then retracted its endorsement following protest from membership.

Since Brian Bowman’s election as mayor in 2014, the WPA has only become a more aggressive player in local politics as Bowman has made minor efforts to curtail police spending.

However, by 2010, all such self-restraints were removed when the WPA endorsed mayor Sam Katz’s re-election campaign within an hour of its launch, a “deal” that had reportedly been struck “some time ago.” Katz was a full-throated backer of the WPA’s “permanent war posture,” campaigning for stronger federal laws and almost 60 new cops, including 20 dedicated to an “anti-gang unit” modelled after its draconian auto theft strategy; Katz even wore a WPA jacket during a campaign event. Along with hosting a press conference to “reaffirm its support” for Katz’s anti-gang strategy, the WPA provided volunteers for campaign work, spent union funds on radio ads and phone outreach, and attacked Katz’s mayoral opponent by claiming her public safety strategy was a “Mary Poppins approach.”

Since Brian Bowman’s election as mayor in 2014, the WPA has only become a more aggressive player in local politics as Bowman has made minor efforts to curtail police spending. In late 2016, just prior to contract negotiations, the WPA organized a door-to-door campaign involving over 100 off-duty police officers, cadets, and volunteers to canvass thousands of houses in some of the whitest areas of the city. In a Free Press letter the day before the canvass, Sabourin wrote: “Mayor Bowman’s willingness to undermine the WPS and cut the resources needed to keep making progress on crime makes it clear a change in approach is required.” Bowman’s attempt to renegotiate the police pension plan – one of the most generous in the country – outside of bargaining led to even greater animosity in the years that followed.

But the knives have now come out for current police chief Danny Smyth, as well. In March 2021, following the death of two cops – including one who died by suicide and whose eulogy blamed anti-police protests – Sabourin lashed out at Smyth due to “morale concerns” resulting from “the chief’s lack of any outreach to the families of these individuals – or to the broader service.” Things quickly escalated, with Sabourin then claiming “there’s no way he can repair this” and calling for a third-party workplace assessment, which a Free Press columnist described as part of an “unprecedented campaign” to “force him [Smyth] to step down.” Soon after, the WPA publicly opposed Smyth’s contract renewal, in part due to his “failure” to adequately fight for sufficient budget increases.

Bowman’s attempt to renegotiate the police pension plan – one of the most generous in the country – outside of bargaining led to even greater animosity in the years that followed.

The third-party review was published in mid-2021, reporting low morale and blaming both Smyth and “current events/political movements” for such dire conditions. As COVID-19 ripped through the ranks of the Winnipeg police – which, like many other police departments, has demonstrated a total disregard for pandemic protocols – Sabourin leveraged the pandemic and a docile press to again push the idea of a besieged, heroic police force, with the only solution on offer being more police and more money.

It was no coincidence that all of this happened right before the WPA entered another round of collective bargaining.

The abolition imperative

The great irony of this all, of course, is that the ever-growing “embattlement” of police can only ever result in more money for policing. But as Masco observed about the U.S. national security state: “by allocating conceptual, material, and affective resources to ward off imagined but potentially catastrophic terroristic futures, the counterterror state also creates the conditions for those catastrophic futures to occur.”

Likewise, the WPA’s ceaseless and surging demands for more funding and supports takes money away from all other public services that would actually keep people safe, such as housing, food, harm reduction, health care, and non-violent crisis response. In turn, this exposes already oppressed people – those who are Indigenous and Black, unhoused, with mental health or substance use issues, and already “in the system” – to even greater levels of criminalization. The “thin blue line” ideology of policing interprets these spiralling conditions as evidence of further attacks on officers’ bodies, minds, time, and morale. To the WPA, the “permanent war” is very literal. It can and will never end, because every perceived issue is reconstituted into the discourse of “crime.”

While existing systems of incarceration, displacement, surveillance, and elimination provide wealthy and white Winnipeggers with a sense of “safety,” they brutally undermine the real safety of everyone else in the city.

The only answer is police and prison abolition. This is necessary not only to reallocate enormous resources to things that actually promote life and safety – a cause to which all other public-sector labour unions should be deeply committed – but to halt the constant production of an atmosphere of racist paranoia, distrust, and fear that legitimizes continued police power. While existing systems of incarceration, displacement, surveillance, and elimination provide wealthy and white Winnipeggers with a sense of “safety,” they brutally undermine the real safety of everyone else in the city.

This requires confronting police unions as a central but little-noticed player in actively generating this atmosphere as a self-serving tool, as well as working to redefine what conceptions of “safety” even mean in the first place. Police unions must be systematically marginalized, excluded, and organized against as right-wing ideological forces.

_780_520_90_s_c1_c_b.jpg)