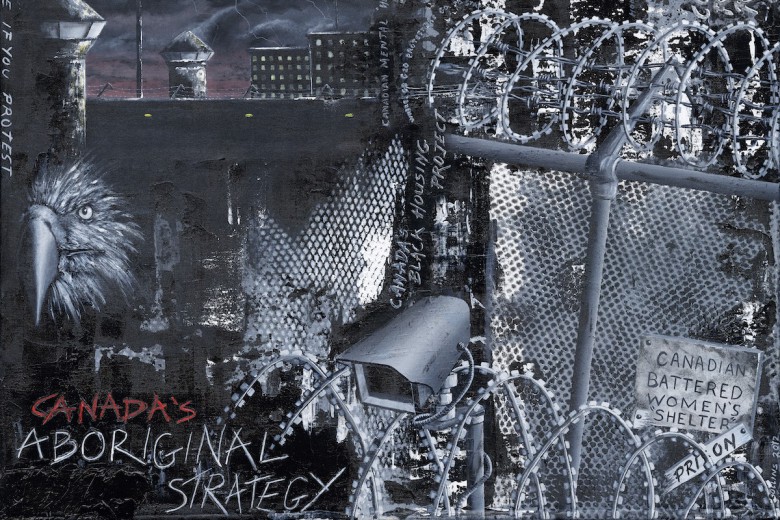

How would life look in our communities if prisons didn’t exist? If our communities had real opportunities instead of being boxed in both physically and mentally by government projects? If our people were uplifted, given a vision of togetherness and equality, not treated like crabs in a bucket trying to win the lotto?

I’m currently incarcerated at the Toronto South Detention Centre (“the South”) pending new charges along with a parole violation. I’m a 31-year-old Métis and Cree man who has been in the system since the age of 13. The government plays a cruel and unfortunately usual game with the lives of those in criminalized communities. The system made me feel like I was doing something wrong before I did any wrong. Would I be in this predicament if I hadn’t lived in a marginalized community or if my friends and I weren’t constantly harassed by police? The government’s agenda is quite clear. They are trying to widen the gap between the rich and the poor and between white people and Black and Indigenous people.

People who are released from prison often reoffend. Why? When someone is released from a federal institution, they are usually on strict conditions that make integrating back into the community nearly impossible. Our parole conditions often say that we are not allowed to interact with people who have a criminal record or pending charges, which means that we must announce our status as a federally owned convict to the people with whom we are in contact so that we don’t breach our conditions. These conditions mean that we can’t see many of our friends or loved ones. The only job opportunities available to released people are normally low-paying factory or construction jobs. Our movement is often restricted, as we are only allowed to leave our jurisdiction or visit certain addresses with prior approval from our parole officer.

Would I be in this predicament if I hadn’t lived in a marginalized community or if my friends and I weren’t constantly harassed by police?

My arrest happened before the second wave of COVID-19. If people thought jail was bad before, it’s a complete disaster now. Programming essential to our mental health has been cancelled indefinitely. Visits from family or friends are prohibited. There aren’t any education opportunities. We don’t interact with anybody other than guards and those in orange. The range is designed to limit movement: our visits, court appearances, and yard time all happen on the range, which makes us feel trapped. Prisoners have an increased risk of contracting COVID-19, yet guards walk in without being tested or vaccinated. All of this makes us feel like we are just a dollar sign and that our lives don’t matter, that we are not worthy of choice or expression. We are constantly told that we do not have rights.

The jail knows we are a vulnerable population, susceptible to abuse at the hands of our captors. Despite this, we are targeted by money-hungry companies that exploit our needs in order to make enormous profits. The jail’s phone system profits off us while straining our relationships. Our calls are limited to 20 minutes per call and whoever answers is charged a collect-call fee. The system has a three-way call detector that disconnects the call if there is a clicking noise or a third voice is heard. Prisoners have filed complaints about the detector to the institutional head and to the ombudsperson but no changes have been made. False and true three-way detections mean we have to place more calls, which translates into more money for the phone companies. The system makes it difficult to call a switchboard to handle our bills or to get a hold of agencies. If we can get through, we often sit on hold for 20 minutes, listening to elevator music, before our call ends. We are forced to handle our affairs, fight our cases, and maintain relationships within 20 minutes. With constant lockdowns and shortened days because of staff shortages, how are 40 prisoners supposed to use four phones in five to six hours? The phone system tears down supports, breaks relationships, and worsens the mental health of those inside, who do not know when their next call will be. The government allows companies to dig deep into the pockets of prisoners while our hands are tied behind our backs.

The jail knows we are a vulnerable population, susceptible to abuse at the hands of our captors. Despite this, we are targeted by money-hungry companies that exploit our needs in order to make enormous profits.

Eurest, our canteen provider, also takes advantage of prisoners. The mark-up on items is double or triple the amount in shops. Canteen items are often poor quality and sometimes discontinued, which allows for more profit for these greedy companies. Eurest also provides our meals, which are pre-made at the Maplehurst Correctional Complex and shipped to the South. These meals have sometimes been prepared six months before they’re served, according to expiry dates that I’ve seen on kosher meals. The South is a new jail, fully equipped with a kitchen. Despite this, the government pays to have meals shipped from another institution.

Access to family, loved ones, and lawyers has been frustratingly restricted at the South. The visitation system is through video calls, but our visitors still have to come to the jail and use the jail’s video screen – they are unable to call from their own phone or computer. Elderly people trek long distances just to see their loved ones on a screen for 20 minutes. Our visitors are often rudely turned away without notice due to lack of staff or security issues. If you take away our supports, what do we have to look forward to or live for upon release? Communicating with loved ones through mail is slow and frustrating. Pictures are often withheld and letters go missing. This amounts to further pressure on our strained relationships. The government tries to break prisoners’ spirits and punish their supports along the way.

There are few opportunities in prison to learn life skills, financial literacy, or anything that could help people upon their release. Since COVID-19, there has been no rehabilitative programming at the South. The government attempted a webinar for prisoners titled “The Black speakers series – Black lives wailing in conflict with the law.” No one on my range was able to attend due to staffing issues. On a couple of occasions, two people have brought worksheets, colouring sheets of cartoon characters, and decks of cards. These people host workout competitions or play card games for jailhouse biscuits and peanut butter. We aren’t even allowed to try to keep ourselves busy. We were once able to order pre-approved paperback books from bookstores, but that program was axed due to COVID. Every outlet of hope has been suffocated, leaving prisoners to twiddle their thumbs until the backlogged court system calls their number.

If the government intentionally criminalizes someone who is poor or racialized, stacking the odds against them to make sure they end up in prison, it’s not surprising that the government would also fail to assist them upon release.

Spiritual and religious supports at the South are scarce. The spiritual or religious support workers are almost never available to see us. Correctional officers are often ignorant and difficult when people ask for spiritual supports, especially when it comes to the needs of Indigenous people. They make excuses about why they don’t provide medicines or smudge bowls for daily cleansing and purification. Racism is evident at the jail among the officers themselves. Four staff at the South recently filed human rights complaints, describing daily racist harassment and being passed over for promotions. If there is rampant racism among officers, I invite you to imagine what goes on between officers and prisoners. Prisoners are harassed or treated unfairly due to their race, but these incidents are rarely reported as the ombudsperson’s phone number isn’t even posted on the unit. If prisoners want to file a complaint, most of them don’t know where to start.

Prisoners are discriminated against based on our prisoner status and are released back into the community without direction or resources. If the government intentionally criminalizes someone who is poor or racialized, stacking the odds against them to make sure they end up in prison, it’s not surprising that the government would also fail to assist them upon release – hence, the vicious cycle of people going into and out of jail. People feel like they are fighting an endless battle that will never be won.

It is evident that the prison system does not work and that people usually come out worse than they went in. It is evident that people are targeted and criminalized based on race and social status. It is evident that the system treats those charged as guilty until proven innocent. So, the question is: what can be done? Can there be more options to serve our time in community to give people a chance to do right? Or should we stop building community housing in blocks around fast food joints, liquor stores, and payday lenders? We are usually a victim of our surroundings. The government tends to group certain people in certain areas and criminalizes them, hoping to suppress and devalue them as humans. We are all connected, and we should treat each other with humanity no matter one’s walk of life. If not, our impoverished communities will worsen. Abolish prisons. Abolish the system.