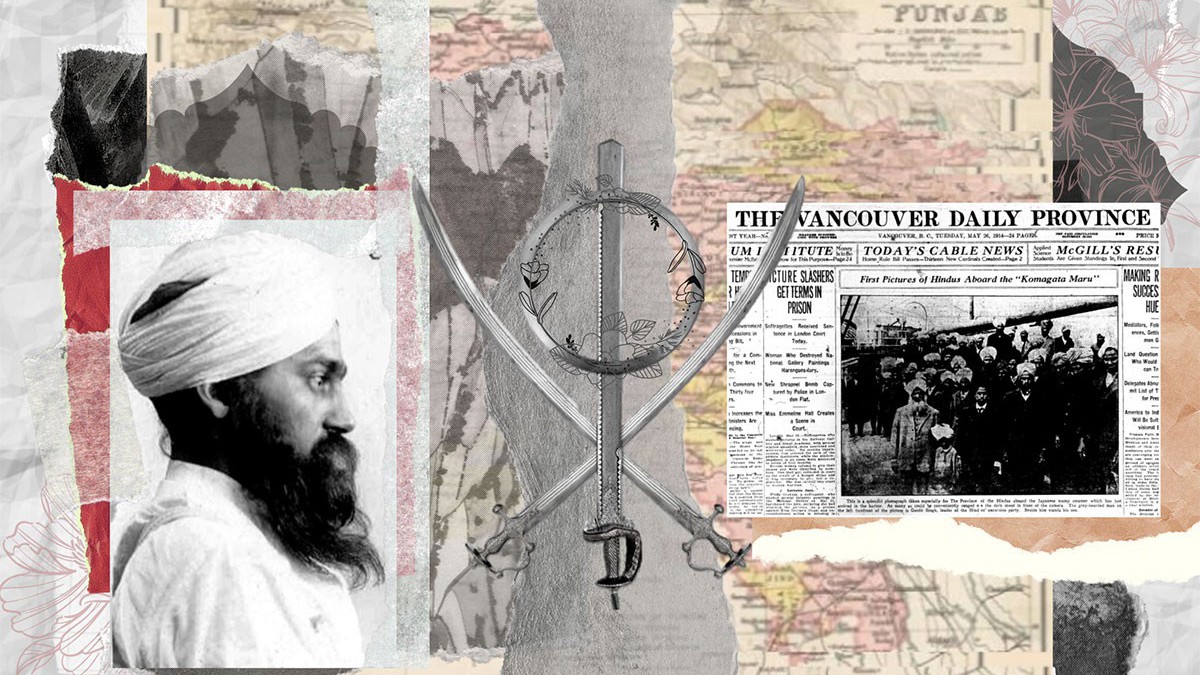

When Jagmeet Singh won the leadership of the NDP in 2017, he became the first person of colour to lead a federal party. It was no coincidence that he was Sikh – since the time of the revolutionary anti-colonial Ghadar Party over a hundred years ago, the Sikh community in Canada has exerted a political power that far outstrips their relatively small numbers.

The mainstream media responded to Singh’s nomination by asking if Canada was “ready for a prime minister with a turban,” puzzling over his kirpan, and fretting over his attendance at a Khalistani rally. The political motivations and history of Sikh people are poorly understood and articulated in Canada. But there’s natural alignment between Sikhi and leftist politics – an alignment that, if made explicit, could be a powerful community mobilizer.

To make that connection, I spoke to Navjot Kaur, an educator and organizer based on Treaty 6 territory in Alberta. She’s a founding member of Courage, a national, member-based group organizing on the left flank of the NDP. In 2016, she ran unsuccessfully for Edmonton’s city council on an explicitly queer, feminist, and anti-colonial platform. Later, she organized within the Alberta NDP, helping to create the Race Equity Caucus.

SD: Can you tell me about yourself and your position in the Sikh community?

NK: I’m a Sikh first, as well as ethnically Punjabi. Though the majority of Sikhs are Punjabi, non-Punjabi Sikhs have also had an important impact on our political history.

I’m kind of both an insider and an outsider in my community. I’m unlike many Sikhs in that I grew up on the Prairies; my family migrated before the 1984 massacre; I wasn’t raised with help from my grandparents; I’m mixed-caste. I don’t have a lot of the obvious markers of someone who is committed to the values of Sikhi – I can’t read or write Punjabi, I cut my hair, and I don’t wear a turban; I don’t have a well-known family name.

Our stories tell of our history as ethnic and religious minorities throughout 550 years of colonial and fascistic oppression, which includes resisting casteism, forceful conversions, British colonialism, and Hindu nationalism.

Within Alberta, I’m known to be a leftist or what many Sikhs call a “comrade.” There is a long tradition of understanding leftist politics within our community. At a local level, I encourage youth (mostly women) to participate in formal political organizing, and I’ve connected with a large network of Sikhs. This network includes Sikhs of all political stripes, and we keep each other accountable as we work within formal political parties and on campaigns.

Like most Sikhs, my political consciousness is tied to our oral tradition. Our stories tell of our history as ethnic and religious minorities throughout 550 years of colonial and fascistic oppression, which includes resisting casteism, forceful conversions, British colonialism, and Hindu nationalism. Although you can find Sikhs at any point on the Western political spectrum, there are key moments and tenets that have formed our political awareness and sense of justice. I believe once these are understood by the broader left, it will be easier to hold Sikh politicians like Jagmeet accountable to values beyond toeing political party lines.

To the best of my knowledge, you describe yourself as a socialist. How do you think Sikhi connects to socialism?

That’s interesting – I would not identify as a socialist. I identify my politics as anti-colonial and anti-oppressive. My theoretical roots are definitely in Marxism, and I find socialism useful as a way to critique capitalism, but the reasons I identify my politics more as anti-colonial and anti-oppressive come directly from Sikhi. And whether or not other Punjabi Sikhs realize it, that’s where their politics come from, as well.

Sikhs have a long political history of being colonized and marginalized – by Mughal emperors, British colonizers, and the Indian state. Sikhi was a philosophy that was founded under conditions of persecution, so a primary tenet of Sikhi is egalitarianism – or universal humanism, if you want to talk about philosophy.

The very first line in our most sacred poetry, the Granth Sahib, is “Ek onkar” – meaning “we’re all one.” Sikhi is young – it was founded less than 600 years ago – and its development was a direct repudiation of Brahminism, the very strict Hindu Vedic hierarchies of caste. Our very first guru, or organizer – frankly speaking, Guru Nanak was an organizer – would do things like wear clothes that mixed elements of Hindu and Muslim dress and then engage people in conversation around class and religion.

Sikhi was a philosophy that was founded under conditions of persecution, so a primary tenet of Sikhi is egalitarianism.

Sikh people may disagree on a lot of things, but a Sikh will never disagree on egalitarianism. So, when we come to topics such as contemporary LGBTQ2S rights, I could talk to the most staunchly conservative Alberta UCP elder and if he identifies as being a Sikh, we can agree that discrimination on the basis of sexuality or gender is wrong. Period. Whether or not he personally feels comfortable with queerness, whether or not there’s cultural homophobia, is almost irrelevant. It is politically and spiritually impermissible to be inegalitarian, since egalitarianism is the basis of how we became politicized as a community.

Whether or not Sikhs identify the principle of egalitarianism as socialist is another question – when it comes to capitalism, Sikh people’s politics are more varied. That’s when we start to see disagreements. This is arguably due to the deep influence that British laws and concepts of private property had within our community over the past few generations.

What are some other tenets of Sikhi that you think connect to anti-colonial or anti-oppressive politics?

If egalitarianism is our principle, other tenets speak to how to live, how to act, how to embody that principle. One of the main tenets is the concept of seva, which, in a nutshell, means “selfless service.” For Christians, charity is a deep principle, whereas for us it’s seva. It’s a subtle difference, but it can fundamentally change the way we embody our politics. It’s an idea that I come back to a lot to think about why I do the work I do as an organizer.

Charity is the idea of lending a helping hand to someone in need, like handing out food at a food bank. Charity is a top-down model, a transactional model, which places people in different social strata – donors and recipients, rich and poor. Seva, on the other hand, is actually a lot more emancipatory than that; the work that it demands is much deeper, like a type of solidarity. Seva asks why and how hunger is able to exist.

Seva, on the other hand, is actually a lot more emancipatory than that; the work that it demands is much deeper, like a type of solidarity.

At Sikh gurdwaras, which are both our places of worship and our civic centres, we serve a community meal – it’s called langar. Anyone can come – no matter your religion, race, caste, class, or gender – and sit on the floor beside us and eat a meal. Unlike with charity, the gatekeeping is not there, the transaction is not there. What we ask for in return, then, is that maybe you come back and make the tea for langar next time. You build the relationship.

That leads me to another principle: communalism. Sitting together, eating together. That’s connected to the imperative to give what you can. We are taught in our bani (our current guiding text) that we are not allowed to hoard.

This is all theoretical, of course. Sometimes the way that people live by these principles is different.

What does it mean to be an Amritdhari Sikh?

Being Amritdhari means that you have committed – publicly, through ceremony – to always represent all five Kakars, or five Ks. It’s not something you’re born into; it’s a choice you make once you’re older, and not everyone does it. It is seen as a very strong commitment to embodying the politics of what it means to be Sikh. It’s a difficult commitment to take, and it’s something you can’t just take off – so it’s deeply respected in my community.

The five Ks are:

1. Kesh, uncut hair. We keep our hair long. This is something that comes up in my work and in my relationships with Indigenous people here, because something that connects us is that respect to hair. And I’ve been using that a lot to speak to my Sikh elders about the physical and spiritual violence of residential schools. That’s the only thing I have to tell Sikh elders: “The colonizers took the kids and they cut their hair off.” I don’t have to say much more than that. We really understand the violence that that signifies.

Before Sikhs adopted covering their hair, only elites wore turbans. But Sikhs co-opted turbans into an symbol of anti-elitism – today, both men and women at any socio-economic class can wear a turban. They symbolize respecting our crowns, our hair.

2. Kara, the steel bracelet. The circle symbolizes humble strength and the infinite connection to creation. It also serves as a reminder to use our hands in the service of others.

3. Kangha, a wooden comb. A utilitarian tool that keeps hair tidy and symbolizes discipline and clarity of mind.

4. Kachera, underclothes. These are worn only by baptized Sikhs, and they represent a commitment to purity and the hukam (order) of being baptized. It is the only mandated dress for baptized Sikhs.

5. Kirpan, the little dagger or sword to be worn to the side. We almost never take that blade out. It symbolizes our duty, as Sikhs, to halt unjust violence when we see it. We’re not pacifists.

As Sikhs, we believe that our bodies are our first homes – so Amritdharis are expected to operate in a way that’s most respectful to the body. Generally, Amritdhari Sikhs don’t get tattoos, and they’re expected to bathe and wash their hair every day. It also means not eating meat or drinking alcohol. (Though it doesn’t always extend to all meat – we consider factory-farmed meat to be unjust and gluttonous, but eating meat that was sustainably hunted is nuanced, because that’s considered an honourable way to treat an animal.)

Jagmeet is the only Sikh politician I can think of who’s Amritdhari – and his brother, Gurratan. For the NDP and leftists, this is significant. Amritdharis are held to a higher standard and are committed to practising community-building equity work. The fact they have chosen the NDP as their political home is not a coincidence.

Why do you use the last name Kaur? And is it the same as Jagmeet using the last name Singh?

It was our last guru, Guru Govindh Singh, who gave us the names Singh and Kaur. So, every single Sikh, our middle names are supposed to be Kaur (for women) or Singh (for men). There are other groups – Hindus, and Caribbean people who were originally from South Asia – who have the last name Singh. But the way in which Sikhs use it, it’s designed so that you can drop your last name and replace it with your middle name. In South Asian society, your last name denotes your caste, your family, your region. So, coming back to being egalitarian and communalist, Sikhs have been given the ability to throw off those signifiers that entrench that hierarchy, and relate to each other based on our shared values.

A lot of Sikhs running for political office will use their last name – especially if their family is powerful or respected – because it links them to their family. So for Jagmeet, who comes from a high-caste family, to drop his last name and use “Singh,” it sends the message that he’s anti-caste and that he’s running on his own values rather than his family’s power or the affiliations of his last name.

When the name “Kaur” was introduced for women, it was meant to signal equality between men and women, since the word originally means “prince.” But today, it’s a lot more common and socially acceptable for men to drop their last name. I dropped my last name publicly when I was running for city council in 2016. That was actually the first thing that Jagmeet asked me when I met him – he asked, “what made you run as a Kaur?” And I told him it was for the same reasons he did it. But the reactions I got for it were different from those that Jagmeet received, because I’m a woman. It may have been more puzzling, too, since I am not Amritdhari.

For Jagmeet, who comes from a high-caste family, to drop his last name and use “Singh,” it sends the message that he’s anti-caste and that he’s running on his own values rather than his family’s power or the affiliations of his last name.

It’s becoming more common for women to go by “Kaur” – especially artists like Rupi Kaur or Jasmin Kaur. And that’s in part because being an artist or poet is an “acceptable” thing for a woman to do. But when you’re a political organizer – asking for dollars, asking for votes – using the last name “Kaur” is seen as a lot more threatening.

When I was campaigning, the first question I would get from other Sikhs would be: “Who’s your father?” I don’t think anyone would ever ask that of a man who goes by Singh – “Who’s your father? Who’s your wife?” They wanted to know what man I was related to, because they wanted to know which man they could talk to if they felt I was out of line. But because I don’t have those connections, my community learned very fast that there was no man to keep me in line, they just had to talk to me.

These are men who have possibly never had a political discussion with a woman. There’s cognitive dissonance that happens, because the elders in my community, now they’re just like, “Oh, you’re one of the boys. You’re like a man.” I laugh, because I’m like, “No, I am a woman. And there are more of us coming.” But they’re getting there, whether they like it or not – which in itself is incredible.

There are only 500,000 Sikhs in Canada – 1.4 per cent of the population – but over 12 per cent of federal Liberal cabinet ministers are Sikhs. Is it fair to say that the Sikh community is especially politically engaged?

Broadly stated and without a direct quote from bani, Sikhs understand our role in society as a balanced one, with participation in both “mir” (governance or stately affairs) and “pir” (spirituality or communal spirit of living). This is the concept of miri piri gifted to us by the sixth guru, Guru Hargobind. Christians like Tommy Douglas have long understood their spiritual connection to society as their connection to political organizing. Sikhs have been given this teaching since the 1600s.

Sikhs understand our role in society as a balanced one, with participation in both “mir” (governance or stately affairs) and “pir” (spirituality or communal spirit of living).

I also believe our politicization comes back to being colonized – having had our own political system prior to colonization, it was really painful to lose our kingdom to the British. And so we had to learn to manoeuvre, as colonized people, in the political system of our colonizer. So within our community, every single person who can vote votes. Today, lots of Sikhs have made a lot of money, and children of those families can be very apathetic about politics – but their parents still insist that their children vote, and they will even tell them who to vote for, and multiple generations of a family will go to vote together.

Lots of politicians understand the power of the Sikh community and the way that power centres on the gurdwaras. I’ve taken white politicians to gurdwara with me, and they get very nervous because they know that how they come across in the gurdwara will determine a lot in their campaign. All the politicians will come to the gurdwaras, they’ll all learn to say Sat Sri Akal, they’ll attend Nagar Kirtan and send greeting cards. I received a card from Andrew Scheer last year for Nagar Kirtan – I have no clue how the federal Conservative Party would have gotten my information other than from gurdwara mailing lists. I don’t see that happening in other migrant communities, and it’s because politicians know that Sikhs will all come out and vote.

I’ve never seen anything like my own community, in terms of political engagement – and I can see that that’s extremely alarming to the white mainstream.

The gurdwara is an important site of Sikh political organizing. Gurdwaras were traditionally seen as a communal place to pray and eat, and for travellers to stay – they were never intended to be a Sikh-only place. But today, on paper, gurdwaras are churches – they have charitable status, they receive donations, they have a board, they have positions of power. They’ve become like little fiefdoms – whole families will take over the board of a gurdwara and control a lot of money from religious donations, and they will be able to influence the politics of all the families that go to that gurdwara. A lot of gurdwara committees will run political candidates, for all different parties – and sometimes the policies of the party they’re running for matter less than their chances of winning.

I’ve never seen anything like my own community, in terms of political engagement – and I can see that that’s extremely alarming to the white mainstream. I want to gently remind those folks, especially on the left, that lots of us live and organize in the echo chamber of white and Christian supremacy. I hope this article encourages white organizers to discuss shared values with the Sikhs in their communities and to support us in learning how to organize more effectively on the left.

There was this sentiment, after Jagmeet was elected the leader of the NDP, that he was elected based on the fact that he signed up a lot of new Sikh members to the party. White NDPers seem to feel that the Sikhs that Jagmeet signed up are not “real members” because they’re not old-guard white Dippers, and they say those new Sikh members have not since continued to donate to or be engaged in the party – they’re “disloyal” to the party. Do Sikh members have a good reason to be loyal to the party?

I definitely heard that same argument. And it’s true that Jagmeet’s team said they signed up 47,000 new members during his leadership campaign, many of whom are Sikhs. But even before Jagmeet ran, I heard white NDPers argue the same thing about racialized candidates here in Alberta – that these candidates were “getting their whole families signed up” for memberships, that kind of thing. But the idea that Sikhs are “disloyal to the party” is pretty laughable to me, because I’ve found the NDP to be extremely hostile to all kinds of people of colour in the party. It’s not a question of loyalty, it’s a question of “how long before we’re pushed out?” It’s very obvious that we’re not welcome. They have no respect for us. They have no respect for our communities.

It’s not a question of loyalty, it’s a question of “how long before we’re pushed out?”

One time I took a young Somali woman to a constituency association meeting, and we were 10 minutes late. The NDP is always paying a lot of lip service to how much they want young women of colour to show up. But we were met with complete antagonism and dirty looks. And then, once the meeting was done, they said “We’re going out for drinks and you guys can join us for that.” I’m a Sikh, she’s a Muslim. We look at them and we’re like, “We don’t drink, thanks.” But that’s where the real politics happen, at the bar after the meeting. Stopping drinking was arguably the worst political move I ever made. I literally instigated a formal party caucus to deal with these institutionalized roadblocks to our participation and authentic existence within the NDP.

Having beers and going to the bar is seen as a perfectly legitimate place to have a political conversation. But when I, as a Punjabi woman, have tea with 15 women in the afternoon with all the children running around, that’s not respected as much or seen as equally legitimate, or as “building the party.” But we all vote, organize, and donate to political causes.

This attitude is what is limiting political education to younger people in our movements. But the NDP is not self-aware enough to understand that the ways in which they organize are alienating racialized people. And I think, long term, in the political career of a racialized candidate, you’re asking them to burn out. You’re asking them to hit a political wall. Because being racialized within the NDP demands so much inauthenticity of you.

Experience has shown me that conservatives are actually better at organizing across difference, in some ways, than the left is. The right has no scruples – they will do whatever, say whatever, to get our communities’ votes. Whereas the left needs to fall in love with us, in a particular way; needs us to be palatable; needs us to talk to them in a way that makes them comfortable.

Long term, in the political career of a racialized candidate, you’re asking them to burn out. You’re asking them to hit a political wall. Because being racialized within the NDP demands so much inauthenticity of you.

And this is what I mean when I say the NDP is doing a disservice to our communities. There’s a generation of Sikh youth who are hitting their 20s and who are now ready to be acculturated into our political organizing environment. And they’re not being given the opportunity. And they shouldn’t have to do it the way I had to do it, or maybe how you had to do it. It’s a lonely road because we’re not invited in.

I know Jagmeet’s presence has inspired a generation of young Sikhs and Punjabis in Brampton to become political organizers, so that they can run campaigns – which is great, but it’s mostly young men. Women remain excluded.

What are some of the most important political issues for Sikhs in Canada, both in terms of what political policies are materially impactful and in terms of what kind of political issues are ideologically or emotionally impactful?

South Asians are thought to be interested only in bread-and-butter economic policies – we’re not asked about what ideologies or emotions animate us politically. The right doesn’t care because they hate us, and the left thinks it’s racist to ask. But we (brown and white people alike) need to understand what animates and structures political life in brown communities, to be able to build our movements.

In terms of social issues, pluralism is a huge one. We insist on our right, for example, to wear kirpan. So my community is very much opposed to Quebec’s ban on wearing religious symbols – even more so than in the Muslim community, because while only women wear hijab, Sikh women and men wear the turban. As I mentioned, each of the five Ks have a deep philosophical significance. So when the state says you can’t wear your kara, your steel bracelet, that’s really outrageous to us. And it brings up old trauma. The incidents of turban-cutting and other hate crimes that occurred after 9/11 have traumatized Sikhs. A Sikh would rather die than take off their turban. So the sentiment is, “I will fight for others’ rights to their religious symbols as well.”

A Sikh would rather die than take off their turban. So the sentiment is, “I will fight for others’ rights to their religious symbols as well.”

In terms of economic issues, lots of Punjabis believe it’s very important to own land, and I think it stems from our insecurity of losing our land to the British. I wouldn’t say land ownership is important to Sikhs, because we’re communalist, but it is important to Punjabis. In B.C., when Punjabis first arrived on this land, we worked as farmers.

For example, when I bought an apartment, my mom – a very stereotypically Punjabi woman – was like, “It’s not a real home because it’s not on the ground. You don’t have any land.” Telling her all the land here is stolen is a moot point. If we had a proper relationship with Indigenous people here, they would teach us that land can’t be owned; we have to be in relationship to the land. This knowledge would bring us back to our own traditional Sikh teachings and our deep respect for sovereignties.

A lot of Sikhs in North America have become very wealthy in the last 25 years. One of the issues I have in my community is with Sikh landlords and the quality of the homes that they are renting out. I was listening to the CANADALAND podcast on the Sahota family, who are multimillionaire slumlords in Eastside Vancouver, and the fact that they’re a Punjabi family did not surprise me. I guarantee that families like that donate to politicians.

Let’s talk about Khalistan. As a lawyer, Jagmeet Singh defended Khalistani militants in court, spoke on pro-Khalistani panels, and lobbied the Ontario government to declare the 1984 massacre a genocide. What does support for Khalistan look like in Sikh communities in Canada?

Khalistan is a sovereignty movement deriving from the Sikh community. “Khalis” means “pure” and “stan” means “land” in Sanskrit or Gurmuki. So it would be a Sikh state in the Punjab region.

We had a Khalistan, once. After the Mughal empire, we became politically militarized – the last guru gave us arms and we created a Sikh kingdom under Maharaja Ranjit Singh in the first half of the 19th century. Our kingdom was quite large; “Punjab” means “of the five rivers,” and it refers to the five rivers that flow from the Himalayas, which our kingdom encompassed. We were the last kingdom to fall to the British, in 1849.

Punjab and its Sikh-majority population were always seen as a threat to the nation-state of India, since we have this distinct political consciousness of our own sovereignty.

After British colonialism, to create the nation-states of India and Pakistan, those five rivers were split up through borders. Since the partition of India and Pakistan in 1947, there have been moves to pare down the territory of the state of Punjab. Punjab and its Sikh-majority population were always seen as a threat to the nation-state of India, since we have this distinct political consciousness of our own sovereignty.

Fast forward 20 years from 1947, and there’s an armed Khalistani sovereignty movement in Punjab, and there begin to be anti-Sikh riots and pogroms. Punjab became a police state. A lot of students, young people, and sovereigntists were killed. A lot of Sikhs were driven to living in the woods. If you were a Sikh man between the ages of 11 and 60, you were seen as a threat by the Punjab police, on order of the Indian government. They just wanted to kill us – or, more accurately, to kill the idea of our self-determination.

People’s Hindu neighbours started turning them into the police. That’s deeply traumatized our community – our neighbours burnt us alive – so now we’re a deeply insular community. We don’t trust Hindus, and we especially don’t trust the state of India.

Our holiest gurdwara, Harmandir Sahib, is in Amritsar – it’s like our Vatican, our political and spiritual centre. In 1984, during Operation Blue Star, the Indian military brought tanks to Amritsar and mass-murdered as many as 8,000 Sikhs in one day, during a very auspicious holiday. The lake around the temple was red. You can still see the bullet holes in Amritsar today.

That’s deeply traumatized our community – our neighbours burnt us alive – so now we’re a deeply insular community.

A lot of people from Jagmeet’s generation – my generation – lost family members during the pogroms. My uncle was a comrade, and he was murdered on the street. That was so normal – if you were talking about Punjabi self-determination, you would just be disappeared.

And on the Canadian left, there’s a lot of knowledge around and solidarity with the Cuban revolution, with Palestinian sovereignty, with Kurdish liberation. But when you talk about Khalistan, those leftists become like every other conservative – every other person who’s scared of “terrorists in turbans.” I don’t know why there’s such a lack of awareness, because Sikhs have been here, on this land, before there even was a Canada, before Confederation. We’ve been part of the labour movement for generations in B.C.

I think a lot of leftists get confused because the media aligns the entire Khalistani movement with the 1985 Air India bombing. There’s a lot of nuance there, and it just can’t be affiliated. Plus, the Indian state really does not like how politically organized Sikhs are in the West, so they take any opportunity to delegitimize us – India even denied Jagmeet a visa in 2013. Imagine if you have people who are seeking sovereignty, who then begin gaining political power in some of the most powerful countries in the world – that’s very unsettling to the Indian state. But what, to me, is really concerning, is that the media is trying to make those affiliations career-enders. By hanging Jagmeet out to dry for attending a Khalistani rally, what they’re saying to all Sikh organizers who are supporting Khalistan is that you can’t have a public career.

Within the Sikh community, Jagmeet’s stance is pretty normal – we’ve all gone to those events. Being an Amritdhari person, especially, he’s assumed to have been taught about our history. So if he was seen to be on the fence about Khalistan, that would be much more concerning in our community – it would be like, “Okay, who do you stand with, then? The Punjab police who massacred us?”

Just as Jagmeet is willing to stand up for Sikh self-determination, he must demonstrate solidarity with those fighting for Indigenous sovereignty here.

Jagmeet comes from a tradition that asserts support for the dispossessed and has long fought against state oppression. I have no doubt that he has a deep ethical commitment to respecting sovereignties, and to anti-oppression. But being the leader of the federal NDP, Jagmeet has also inherited the colonial traditions and policies that come with the party. My Indigenous relations really gave Jagmeet a chance this last election, but despite some good rhetoric, his track record on respecting Indigenous sovereignty and treaty leaves a lot to be desired. Just as Jagmeet is willing to stand up for Sikh self-determination, he must demonstrate solidarity with those fighting for Indigenous sovereignty here – not only because we are mandated to stand up for justice, but also because Sikhs must educate each other on our responsibilities, as settlers, on both treaty and unceded Indigenous land.

Jagmeet has an opportunity to introduce the left to our Sikh consciousness and political logics. Post-9/11, there’s a widespread Islamophobic fear of ways of organizing and epistemologies outside the Western and Christian model. But we need both our leadership and our comrades to value the potential that Sikhs have to advance movements for communalism and anti-oppression. The left needs to be willing to engage across difference, to broaden our ideas of which legacies are legitimate. I hope this article will help readers open political dialogues with Sikh organizers, politicians, and neighbours in their communities, asking them directly what their values are and how they can help strengthen our movements.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.