This article was originally published in Upping the Anti.

The recent uprising in response to the police murder of George Floyd has sparked widespread condemnation of anti-Black police violence and growing acceptance of radical alternatives to the police. On June 23 2020, the Centre for Addictions and Mental Health (CAMH) joined the chorus of condemnations after the murder of Ejaz Choudry by Peel Regional Police during a wellness check. In a statement, CAMH argued, “Police should not be the first responders [...] people in crisis [should be] first met by mental health responders”.

But this suggestion—to replace the figure of the police with that of the mental health worker, requires closer scrutiny. Missing in this analysis is recognition that the mental health field has an ongoing history as a major perpetrator of racial and colonial violence alongside the police.

Today, Black, Indigenous, and people of color are disproportionately diagnosed with schizophrenia, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and other diagnoses. Receiving a psychiatric diagnosis can pave the way for chemical restraints, community surveillance, and other forms of coercion. For instance, a British study found that Black people were disproportionately targeted for involuntary hospitalization.

Missing in this analysis is recognition that the mental health field has an ongoing history as a major perpetrator of racial and colonial violence alongside the police.

And given the widespread collaboration between the criminal justice system and the mental health field, involvement in one increases exposure to the other. In Ontario, a Form 1 orders the police to bring a person involuntarily to a psychiatric facility, and can be issued by a justice of the peace, a physician, or a police officer themself. While a community treatment order (CTO) permits police interventions towards involuntary hospitalization should the person fail to follow a treatment plan.

The widespread targeting of racialized people by psychiatric institutions is unsurprising considering that racism and psychiatry have shared roots in the theory of degeneration. Developed in the late-18th century, degeneration theory posits that all races have a common origin in the ‘Caucasian race’, and only developed differences through deterioration and devolution caused by environmental factors like climate, nutrition, and cultural upbringing (Lenoir, 1980).

The widespread targeting of racialized people by psychiatric institutions is unsurprising considering that racism and psychiatry have shared roots in the theory of degeneration.

This degeneration was thought to cause both differences in physical appearance, and the deterioration of mental and intellectual capacities, exhibiting itself as mental disorders. German psychiatrist Emil Kraepelin (1919), who published one of the first compendiums of mental diagnoses in 1883, argued that degeneration “certainly play[ed] a part in the development of dementia praecox” (Zubin et al., p. 239), the forerunner to schizophrenia, and could be used to explain many psychological disorders.

The concept of degeneration influenced Francis Galton’s notion of eugenics, the science of “improving” the genetic quality of a population by encouraging the procreation of White non-disabled people, while preventing the procreation of others deemed as defective and inferior.

It was no accident that eugenics first gained prominence in the context of colonialism. This deep entanglement between disability and race served to justify colonialism by presenting the people of the colonized world as less abled, child-like, and sub-human; consequently, the subjugation of colonized peoples was not considered a moral transgression and instead, simply a natural phase within human evolution (Levine, 2010).

These activists’ resistance against racism was understood as pathological.

The conceptualization of mental disorder as rooted in race provided the ideological justification for white supremacy and was employed as a means of control. A particularly stark example of this is drapetomania, the “mental disease” assigned to Black enslaved people who ran away. The use of physical violence was prescribed as the cure to return Black enslaved people to their ‘normal’ state of subservience (Mama, 2002). Psychiatrists also diagnosed thousands of Black civil rights activists with schizophrenia to justify their detention in asylums in the 1960s and 1970s. These activists’ resistance against racism was understood as pathological (Metzl, 2010).

The mental health field, born out of the eugenics movement, is also responsible for other forms of systemic racial violence. The Canadian National Committee of Mental Hygiene (CNCMH), the precursor to the Canadian Mental Health Association, was established in 1918 as a major advocate for coerced sterilization, anti-miscegenation, and immigration control.

Coerced sterilization was implemented in several Canadian provinces, disproportionately targeting Indigenous peoples. In Alberta, mental health workers identified people to be diagnosed as ‘mentally defective’ to allow for consent requirements for sterilization to be waived under the Sexual Sterilization Act of Alberta, which was made into law in 1928 (Samson, 2014). In British Columbia, the government created boards, consisting of a psychiatrist, a judge, and a social worker, to make decisions around the sterilization of inmates deemed likely to have a mental illness by way of inheritance (McLaren, 1990).

This advocacy led to the broadening of categories of disability prohibited by immigration policy and the deportation of those deemed mentally ill.

Coerced sterilization continued throughout Canada even after the repealing of sterilization legislation in 1972 and 1973. The most recent documented case occurred in 2017, when an Indigenous woman was asked, while under anesthetics and in a state of panic, to undergo sterilization. The same year, class action lawsuits against various levels of government were filed in Saskatchewan and Alberta regarding coerced sterilization, turning up hundreds of cases.

The CNCMH also opposed miscegenation, based on fears that interracial ‘breeding’ would lead to racial degredation. Interracial relations were often prevented through legal means. In 1939, Velma Demerson was incarcerated for nine months after choosing to live and have a child with Harry Yip, a Chinese man. This was made possible by the Female Refuges Act, which permitted parents to bring about legal intervention for young women deemed “unmanageable or incorrigible” (Valpy, 2002).

Extralegal violence was another method of anti-miscegenation, with the Ku Klux Klan harassing or kidnapping inter-racial couples (Backhouse, 1999). Finally, the Indian Act discourages marriages between Indigenous women and non-Indigenous partners, by stipulating that Indigenous women who do so lose their Indian status, and children of these marriages are not entitled to obtain status.

Considering the shared origins of psychiatry and racial hierarchy, and the mental health field’s long standing participation in racial violence and the policing of racialized bodies, people should be critical of calls to replace one institute of state violence through a strengthening of another.

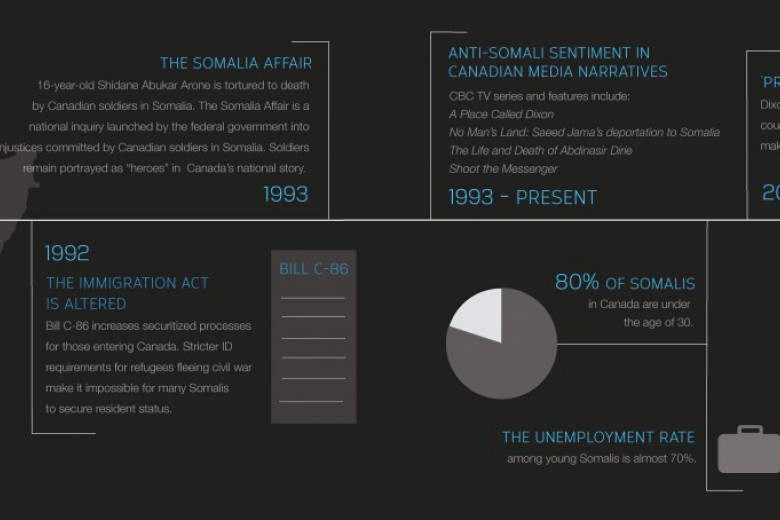

Anti-miscegenation perspectives also influenced demands by the CNCMH for more stringent immigration controls. It was feared that immigrants would ruin Canada’s gene pool through miscegenation and overtake White people in numbers through higher reproductive rates. This advocacy led to the broadening of categories of disability prohibited by immigration policy and the deportation of those deemed mentally ill. A prominent case involved the deportation of 65 Chinese mental patients from Vancouver to Hong Kong in 1935.

And while an overhaul of immigration policy in 1976 removed mentions of specific diagnoses, immigration policy now justified exclusion on the basis of medical inadmissibility, which included not only potential public health risks but also the likelihood to place an “excessive demand” on social services (Mosoff, 1998). Although not explicitly discriminating against disabled people as a group, current immigration policy still has the effect of barring many people with disabilities, including mental illness, by requiring physicians and the courts assess the potential demand the individual applicant will place on the system (an assessment which reproduces capitalist notions of productivity).

Considering the shared origins of psychiatry and racial hierarchy, and the mental health field’s long standing participation in racial violence and the policing of racialized bodies, people should be critical of calls to replace one institute of state violence through a strengthening of another.

People should also consider the reminder from Roland Chrisjohn, activist scholar and member of the Onyota’a:Ka, that emotional distress is a social problem rooted in racism, sexism, capitalism, and colonialism.

Instead, people should consider responses to crises informed by perspectives from mad people themselves. Mad movement activists have long called for mad literacy, a willingness to understand those whose behaviours do not conform to social norms, and skill sharing, to allow for community-driven approaches to crisis intervention not predicated on violent coercion. For example, Bonnie Burstow, the late mad movement activist and professor, suggested community befriending, a return to an emphasis on basic human relationship building by community members to creatively support a person before, during, and after a crisis.

People should also consider the reminder from Roland Chrisjohn, activist scholar and member of the Onyota’a:Ka, that emotional distress is a social problem rooted in racism, sexism, capitalism, and colonialism. Substantively addressing this distress requires directly confronting racial and colonial violence, including the violence perpetrated by the mental health field.

_780_520_90_s_c1_c_b.jpg)