As I write this, the United States is in the midst of the presidential primaries. Like many of his now-vanquished Republican Party rivals, Donald Trump, the nominee for the Republican Party, denies climate change. He has long insisted that human behaviour has no bearing on the climate, dismissing it as a cause unworthy of concern. “Ice storm rolls from Texas to Tennessee,” tweeted Trump in 2013. “I’m in Los Angeles and it’s freezing. Global warming is a total, and very expensive, hoax!” More recently, he characterized climate change as “a very, very expensive form of tax.”

Trump’s is a position that the left can scoff at, if not altogether dismiss. Climate justice activists rightly point to the scientific consensus on climate change: the Earth’s climate system is warming, with dire consequences for people and ecosystems, and human activities have been the “dominant cause.”

But for deniers of climate change, a cold day in the land of year-round sunburns trumps (pun intended) the conclusion reached by thousands of scientists who have been studying myriad sides of the question for decades. Common sense rules; expertise is suspect.

The appeal of common sense

Common sense has extraordinary appeal. “It is a form of popular, easily available knowledge,” Stuart Hall and Alan O’Shea write, requiring “no sophisticated argument, and does not depend on deep thought or wide reading.” It simplifies the complex, making clear-cut what is complicated, and it does so by appealing to a person’s own experience.

As activists, we pride ourselves on being critical thinkers who see the forest for the trees, but the truth is, we aren’t above resorting to “common sense” arguments. Take, for example, the Leap Manifesto, introduced by a coalition of Indigenous rights, social and food justice, environmental, faith-based, and labour movements. The call-to-action argues that “the new iron law of energy development must be: if you wouldn’t want it in your backyard, then it doesn’t belong in anyone’s backyard.”

On its face, the statement sounds morally indefeasible, fair, and just: I shouldn’t ask you to live with something I wouldn’t live with myself. Most people wouldn’t want to have an open-pit tarsands mining operation down the street. But for many people, green energy solutions (wind turbines, solar farms) aren’t welcome neighbours, either. The “common-sense” approach makes for an appealing slogan, but as an approach to developing campaign goals or policy, it is overly simplistic.

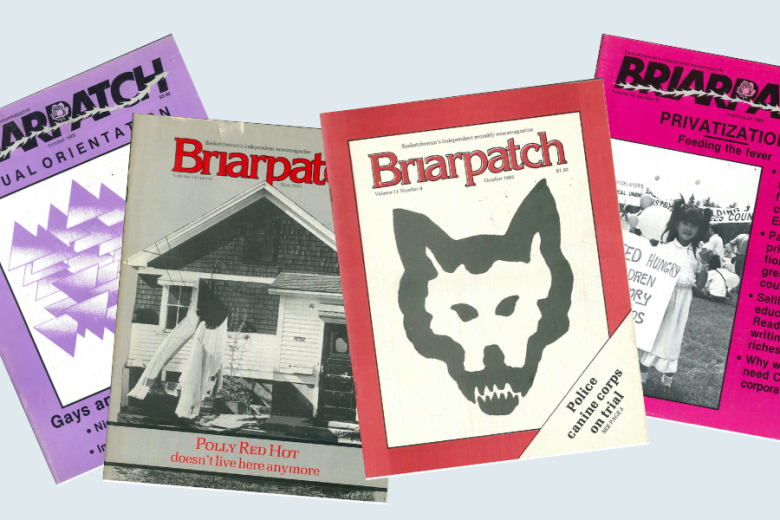

For the radical left, which has set itself the daunting tasks of dismantling capitalism, white supremacy, patriarchy, and colonialism, falling back on simple solutions does our work a huge disservice. Michelle Stewart wrote once in the pages of this magazine that “systemic issues are not issues of immediate resolution” and we must not avoid the “messy, troubling, and difficult work” required of us. Our work, like the world we strive to change, is quite complex. If we hope to succeed, we need to embrace expertise.

Expertise

Expertise is specialized knowledge on, judgment about, or skill in a subject. It’s not something one is born with. It’s gained through labour, study, and experience. By definition, it’s uncommon.

Expertise is often disavowed by both the right and the left, and seen as inseparable from elitism and illegitimate authority. For populists on the right, expertise is the domain of elites and technocrats; it runs counter to common sense or accepted social biases and is used against the people. On the left, feminists like Patricia Hill Collins and other radical academics reject the presumption of power-neutral epistemic authority, arguing instead that all knowledge is situated in social locations. Claims of knowledge and authority have long favoured the stories and realities of the powerful and privileged in society.

Levi Gahman, in a recent essay about neoliberal education for ROAR Magazine, explains how the Zapatista movement works to develop methods of knowledge transfer that champion mutuality and dignity instead of competitive individualism; teachers refuse vertical rank, professional titles, or credentials. Zapatistas, he writes, “are unsettling the rigid boundaries dividing ‘those who know’ from ‘those who do not know’ – because there is nothing revolutionary about arrogance.”

But Gahman, like many on the left, oversimplifies things. Notwithstanding his discussion about the possibilities of better, more dignified ways of learning, and the important interventions of feminist and anti-capitalist epistemic theory, the fact is, there are “those who know” and “those who don’t.” To acknowledge this imbalance (or hierarchy) is not to side with arrogance. Such a hierarchy is not inherently oppressive, even if it may open up the possibility of abuse. It’s only oppressive when society confers upon the expert some special privilege that functions to exclude or discredit others with legitimate knowledge, or when experts use their knowledge or skills to gain or hold power over others.

A single activist, no matter how dedicated to the movement, cannot be expected to know everything about the intricacies of the systems impacting social and political life, nor possess the myriad skills needed to sustain and build a social movement capable of changing the world. Our tasks as radicals are monumental and multi-faceted. Our work is also urgent.

The question is not whether we should trust experts. We already do (the engineers, biologists, and plumbers who bring us our clean drinking water, the computer programmers and designers who build the communications technology we use daily, the academics who study racism and patriarchy, the people with lived experience of oppression who know how the system impacts others like them, for example). Rather, we need to ask: What expertise does the movement need if we are to accomplish our goals? And how do we know whom to trust?

Why expertise?

For several years, I was a member of Ontario’s Movement Defence Committee (MDC), a working group that provides legal support to activists. I have some legal training (I graduated from a two-year paralegal diploma program, have defended low-income taxi drivers in traffic court, and represented people in minor lawsuits against the police) and personal experience (I’ve been arrested and charged for protests in the past). These experiences, however, do not make me an expert in criminal defence, even if I know what the process looks and feels like. In order to provide “Know Your Rights” training to activists, as I did when part of the MDC in the lead-up to the G20 protests in June of 2010, I had to ensure that the information I was sharing with activists was legally correct and up-to-date, and the only way to do this was to consult experts in criminal defence.

When the week of protest against the G20 ended with well over a thousand people detained and dozens charged – including 17 organizers who faced serious criminal conspiracy charges – the MDC connected activists with competent criminal counsel, many of whom were active MDC members. Challenging the state on its terrain requires not only knowledge of the law, but also skills and judgment in the courtroom – expertise gained through a combination of legal education and experience with the court system.

I don’t wish to minimize the success of a small number of activists who have represented themselves in court (which often still requires expert assistance behind the scenes), nor do I want to ignore the personal empowerment that may result from self-representation, but the legal system is such a specialized space, and the stakes so high, that experts in the law are indispensable.

In the case of preparing for the G20 protests, it was easy for us to identify which experts to trust. We knew we had political affinity with many lawyers based on previous experience, and for the others, the practising lawyers in the MDC knew which of their professional colleagues were appropriately skilled to be trusted with difficult cases – the networks of trust were in place. Things get difficult when the knowledge, judgment, or skills that we need don’t readily exist among our allies. How do we know whom to trust when we need experts to inform our work?

Cynical thinking or critical thinking?

It’s not easy to sift through competing conclusions by self-identified experts when we are only superficially familiar with a subject. The task can seem all the more difficult when we consider society’s gendered, racial, and classed presumptions of authority. It’s simpler to side with the expert whose conclusions confirm our own set of assumptions and values while quickly dismissing those with whom we disagree (scientists call this confirmation bias). When we do so, we are engaged not as critical thinkers, but as cynical ones. We are using the same blinkered thought process as those who deny climate change.

Rebecca Solnit, writing recently in Harper’s Magazine, describes this mindset, present on the right as much as on the left, as naïve cynicism. Cynicism, she writes, “takes pride more than anything in not being fooled and not being foolish.” Cynics oversimplify and engage in “a relentless pursuit of certainty and clarity in a world that generally offers neither,” shoving “nuances and complexities into clear-cut binaries.”

In contrast, critical thinking is not about passing judgment, but about evaluating a problem by gathering and assessing relevant information, including the work or opinion of other experts in the field, recognizing both your own and the experts’ inferences, assumptions, and implications, and coming to precise conclusions that are testable and defensible both by reasoning and when measured against your values and your politics. It also entails accepting ambiguity and complexity when there simply isn’t a clear-cut answer, at least not yet.

The only way we can evaluate whose “expert” opinion to trust is to critically assess all expert claims, regardless of the expert’s politics or lived experience. Using critical, not cynical thinking is to truly put an anti-authoritarian politics into practice.

Activist-researchers Chris Dixon and Douglas Bevington argue that social movements need to get the best available information, even if it doesn’t match up with our expectations or with current movement orthodoxy; they cite Frances Fox Piven and Richard Cloward’s research that shows that social movement organizations can actually dampen rather than grow possibilities for social change. We should accept that sometimes people we disagree with politically may be the most accurate or truthful on some issues (the reverse – that our allies can have the facts wrong – also holds true), and that to learn from them does not mean we are endorsing their world view. Many climate scientists, for example, champion green capitalist alternatives. They may be wrong about their support of capitalism, but they may still be trustworthy on matters of science.

If our social movements are to succeed, we need to be more than just morally right; we need to be factually correct. It’s not always possible, given the complexity of the world, but it is something we must strive toward.

In the hard work of world-changing, there is much we need to understand and many skills the movement as a whole needs to wield. When we consider whether to seek expert assistance regardless of the issues, it’s incumbent upon us to keep in sight the goal of building the power and momentum necessary for changing the world. We need to make the best possible use of the time and effort of everyone in the movement. None of us can know or do it all.

I, for one, would welcome the help of a few experts.

Editor’s Note: The print version of this article incorrectly states that Frances Fox Piven and Richard Cloward’s research “shows that social movement organizations can actually dampen social change when they pursue only the information that matches their political assumptions.” Fox Piven and Cloward do not, in fact, state that social change dampens as a result of pursuing only the information that matches their political assumptions. This was an error in editing, and the Editor apologizes to the writer. A printed correction will run in the September issue.