Forty years ago

Beth Smillie

When I was editor of Briarpatch, we celebrated the magazine’s 13th birthday with an adolescent bash involving lots of alcohol.

I don’t think any of us imagined the magazine would survive to celebrate its 50th. We were always fundraising.

The annual Briarpatch banquet was already a well-established tradition when I started working at the magazine in the ’80s. Almost everyone who bought tickets to the supper volunteered for the event: cooking, serving, or cleaning. It was a labour of love, bringing together a tightly knit community often referred to as “the Briarpatch crowd.”

I moved to Regina in order to become Briarpatch’s editor in September 1982, replacing Clare Powell who went to work at the Canadian Union of Public Employees (CUPE). I was joined over the next four years by Glen Brown, George Manz, Kate Kokotailo, Denise Hildebrand, Keith Cowan, and Chere Mitchell, among others.

That year, 1982, the Conservative government of Grant Devine swept to power in Saskatchewan, reducing the NDP to rubble.

"Convinced the public sector was an evil that had to be exorcised, the government relentlessly cut spending on services for people and increased handouts for the business class."

Over my four years as Briarpatch editor, we witnessed (and wrote about) the Devine government’s obsession with dismantling the public sector. It started in 1984 with government’s decision to sell off the Saskatchewan Department of Highways’ equipment at auction. Then-highways minister Jim Garner said nearly 400 highway workers were being given “an opportunity to work in the private sector.” He meant “fired.” The government auction recouped only 15 cents on the dollar. It presaged the abolishment of the much-loved children’s school dental program in June 1987 during the Conservatives’ second term, when more than 400 dental workers lost their jobs because the Devine government wanted to give the work to dentists in private practice.

Public sector services were a frequent target of government cuts: women’s shelters and social assistance payments were some of the first on the chopping block. Demonstrations and protests over lunch hours became common. The cuts had lethal consequences.

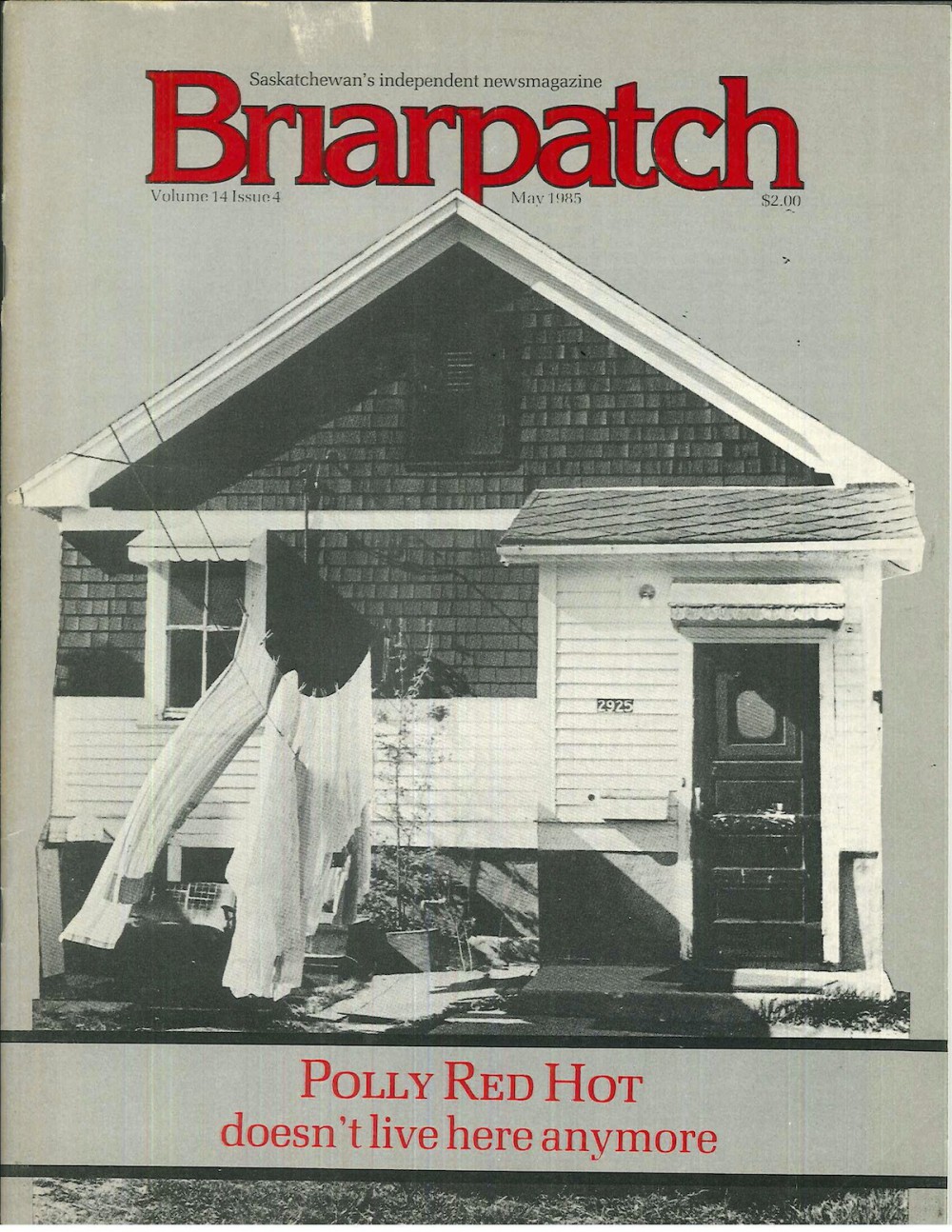

In the fall of 1984, a 64-year-old Indigenous woman named Polly Red Hot was found dead in her Regina home. An autopsy revealed she had died of carbon monoxide poisoning. As Ray Sentes wrote in the May 1985 issue of Briarpatch, her death was due in part to the Conservative government’s right-wing ideology: “Convinced the public sector was an evil that had to be exorcised, the government relentlessly cut spending on services for people and increased handouts for the business class […] At the time of the incident there were only four [gas] inspectors in Regina. Previously, there had been seven.”

The story revealed a sequence of government understaffing and landlord indifference. A month before her death, a SaskPower serviceperson visited Red Hot’s house and found a faulty furnace. The report that he then filed to the government’s Gas Inspection Unit disappeared, only turning up on an inspector’s desk the week after Red Hot died. Meanwhile, to slash budgets, the government had abandoned its policy of inspecting all new gas and propane units. SaskPower did tell Red Hot’s landlord about the faulty furnace – but the landlord did nothing to fix it until after Red Hot’s death.

Rereading that story nearly 40 years later, I wish I had learned more about Polly Red Hot. How had she ended up living in poverty in a run-down house on Saskatchewan Drive? What was her story?

My stint at Briarpatch remains memorable 40 years later. The Briarpatch crowd enriched my life in so many ways. I am grateful I had the opportunity to work as its editor.

Bursting privatization’s bubble

Adriane Paavo

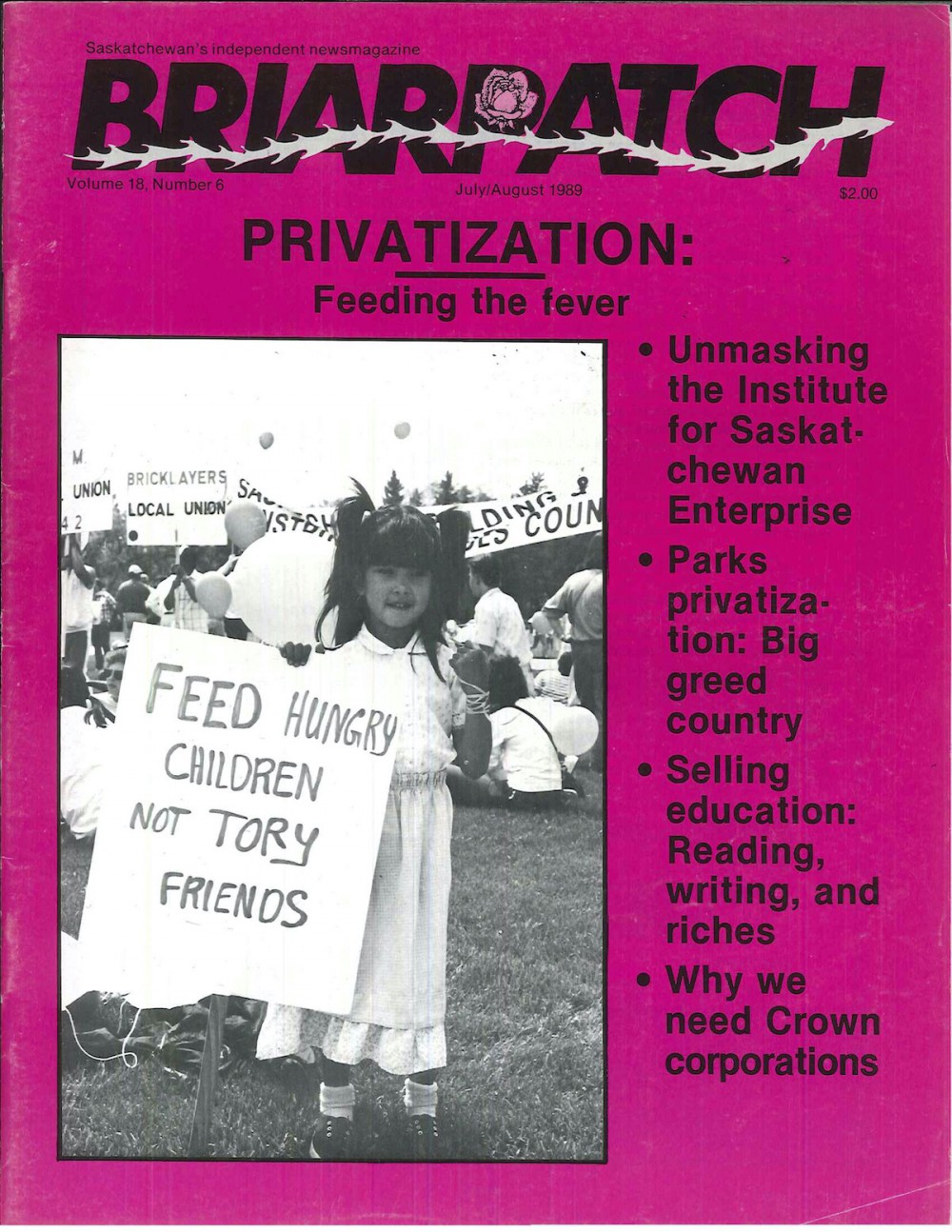

In the late 1980s, most of Briarpatch’s content was written by Saskatchewan social justice activists. The magazine was a record of mobilization and protest by farmers, feminists, environmentalists, and, above all, those affected and offended by the policies of Grant Devine’s Conservative government. The 1980s were the heyday of Tory privatization efforts, and Briarpatch was committed to shining a light on them.

The late 1980s was also a time before the internet and email. Briarpatch staff and reporters did their research by interviewing people and reading documents. We talked, telephoned, and wrote letters. Investigative journalism didn’t yet have its great cyber-tool.

So when the CEO of IPSCO, one of the biggest steel companies in North America, Roger Phillips, set up the Institute for Saskatchewan Enterprise in 1988 to promote the privatization of public assets, he probably felt the coast was clear. The institute’s ads and publications boasted of a board made up of local economic luminaries who were boosting privatization because it was objectively good, not because of any personal bias. And when the Institute for Saskatchewan Enterprise announced a grand international privatization conference to be held in Saskatoon in 1990, the tone was more victory parade than think tank. Phillips – and, by extension, Devine and his government – were to be crowned with laurel leaves on the stage of the Centennial Auditorium. (Irony of ironies, IPSCO started life as a Crown corporation!)

Other Saskatchewan media weren’t questioning the institute’s claims and motives, but I wanted to know more. Fortunately, the Regina Public Library and the Legislative Library had good collections of microfilm, corporate and industrial directories, encyclopedias, and other research resources. Pay dirt!

Australian and British politicians whose failed privatization efforts back home had been rejected by voters, discredited American bag-men who’d sold off public housing to make their own fortunes in real estate, Canadian businessmen with thinly disguised interests in acquiring Saskatchewan public assets at fire-sale prices – that’s who was on the institute’s board. That’s who the international conference was presenting as the new economic wizards.

Briarpatch ran a feature story on the institute’s board, but within the social justice community, energy was building to do more.

The Saskatchewan Federation of Labour, under president Barb Byers, drew together a squad of union staff and community activists. Briarpatch, the Grain Services Union News, and other publications secured media credentials. The Saskatchewan Federation of Labour booked us a command centre in the Bessborough Hotel, where we installed a (then) state-of-the-art dot-matrix printer and computer with desktop publishing software. Our people attended events, then ran back to the command centre to report in. GSU staff rep Larry Hubich and I used the Briarpatch research to create twice-daily media briefing sheets (printed oh so slowly on the dot matrix), which our people handed out at the conference and faxed to the media. And we held news conferences to give the mainstream media another perspective on privatization, along with solid information on the conference dignitaries.

After it was all over, we almost felt sorry for Roger Phillips. The conference was a flop, and we had helped with that. Our success energized us. As we know in hindsight, we would need all the extra energy we could get, because the battle to keep public assets as collective goods continues to this day.

Queerness and liberation

Shayna Stock

I was hired as Briarpatch’s publisher back in 2007. At the age of 23, I possessed the basic skills, drive, and political leanings for the job, but I also had a lot to learn – about my own personal identity, journalism, anti-oppressive politics, and the ways that all of these things connect. Lucky for me, Briarpatch was a generous teacher.

I came out as queer partway through my tenure at Briarpatch. What became ever more evident to me while working there was how deeply interwoven interpersonal politics are with state politics. This is one of Briarpatch’s greatest contributions to the broader media landscape: consistently drawing direct lines between government policies and their impact on people’s lives, between state violence and interpersonal violence.

During my time at Briarpatch (2007–2012), there were a few articles that have stayed with me for that reason – all of them happen to be in the May/June 2011 issue. We published an interview with Judith Butler in which Butler defines the word “queer” as being inherently about being in “alliance” with others struggling for justice and draws links between the politics of queerness and the politics of war. Then there was Robyn Maynard’s piece “Safer Sex Work", which looks at the impacts of prostitution legislation on sex workers and advocates for decriminalization. Finally, an interview with Mimi Kim, where she discusses how poverty and other forms of state violence make people more vulnerable to interpersonal violence and challenges the reliance of mainstream anti-violence movements on police and prosecutors.

This is one of Briarpatch’s greatest contributions to the broader media landscape: consistently drawing direct lines between government policies and their impact on people’s lives.

As I was beginning to name and know my queerness, these articles helped me to understand that part of my identity as inherently connected to a broader political project: the liberation of everyone from all forms of oppression.

Perusing the Briarpatch archives, it’s clear that although not every article has stood the test of time, the magazine has consistently held space in its pages for the struggles and movements of LGBTQ people.

In 1979 and 1980, for example, Briarpatch published a series of reports on the NDP government’s lack of meaningful follow-through on their promises to advance human rights legislation, including a failure to prohibit discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation. “Because of the NDP government’s lack of political courage, gay men and women continue to face blatant discrimination in employment, housing, education and public services against which they have no legal recourse,” Ross Bell wrote in the February 1980 issue.

In the July/August 1979 issue, Edith Mountjoy profiled the Saskatchewan Gay Coalition, a networking and advocacy group that had recently formed to unite gays and lesbians in rural communities. At the time of writing, they had 1,300 members and saw their mandate as both social and political: “Members […] are reminded that politics affect their daily lives in a society where admitting you are gay means becoming an outlaw.”

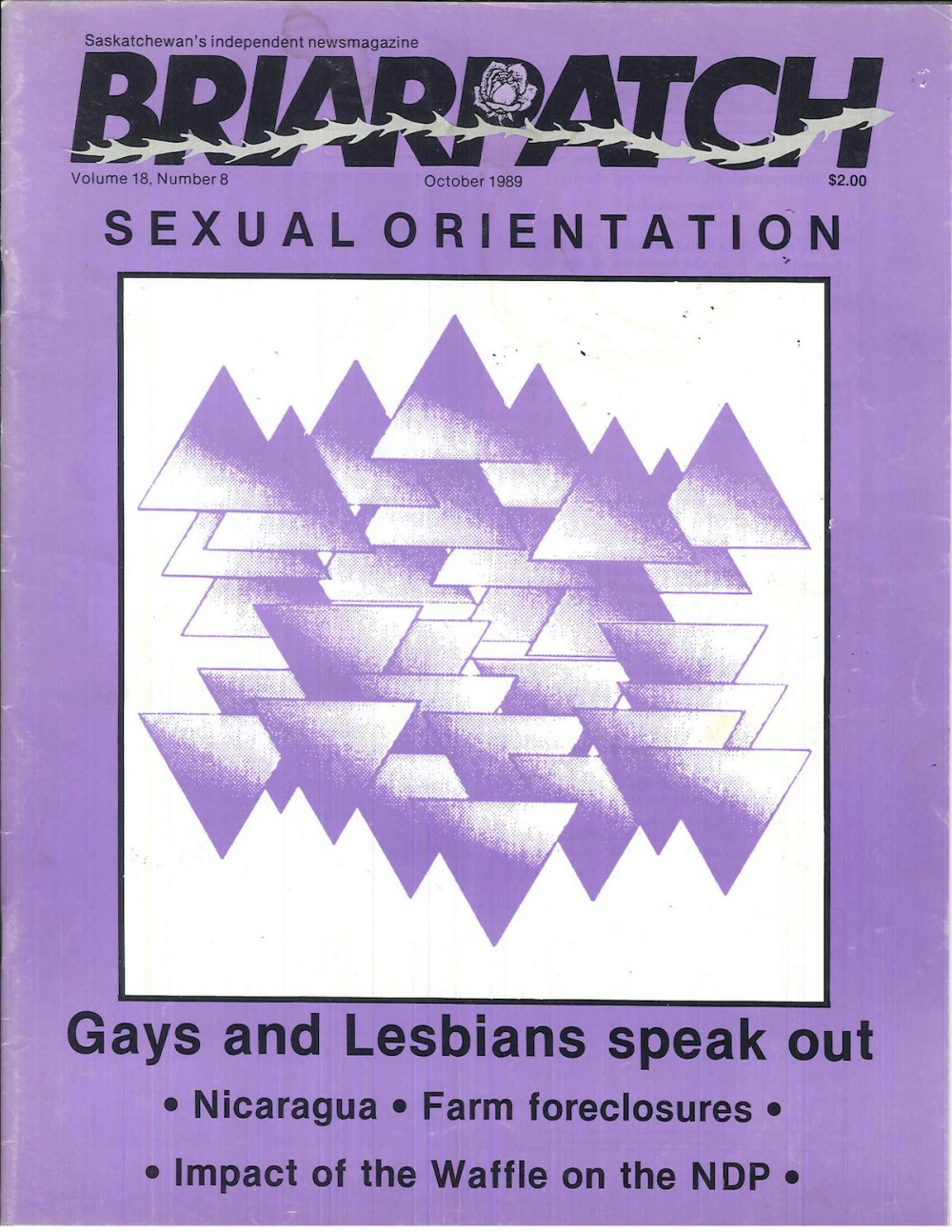

An entire theme issue in October 1989 focused on gay and lesbian rights, including a retrospective on the 1978 protest against U.S.-based anti-gay speakers touring through Moose Jaw; an interview with “Canada’s most vocal gay man,” Doug Wilson, in which he critiques the fixation of gay activism on achieving protection in human rights codes; and an analysis of how the AIDS crisis radicalized many gay and lesbian people as they watched governments and health-care providers turn away from – or worse, actively contribute to – the deaths of their friends and loved ones.

Recent Briarpatch editors and writers continue to make the links between movements, policy, and the personal. In recent years, Briarpatch has covered the 2019 #TakeBackTPL protest against the Toronto Public Library giving a platform to transphobes; the role of trans liberation in the Land Back movement; and the growing struggle to access gender-affirming health care in rural Canada.

Briarpatch implores us to see and nurture the connections between our shared and distinct struggles; it brings our movements into conversation with one another; it personalizes the political and politicizes the personal. This was a powerful gift to me as a young queer, and I trust that many others will continue to find community in the pages of this feisty li’l rag for years to come.

50 years of lighting the path

Andrew Loewen

On December 10, 2014, then–Briarpatch board member Simon Ash-Moccasin was walking by the Casino Regina, on his way to Briarpatch’s annual Christmas party, when he was racially targeted, physically assaulted, and unlawfully detained by Regina police. After his release that evening, Simon made his way to the Christmas party where he told me what had just happened. Simon’s racist assault that night ignited a resurgence of grassroots anti-police organizing in Regina, led in significant part by local activists connected to Briarpatch.

In the new year, a community meeting in Regina’s north end was held at SWAP, the Street Workers’ Advocacy Project, drawing dozens of mostly Indigenous residents to talk about police violence and harm. Working with SCAR, the Saskatchewan Coalition Against Racism, a new grassroots group was formed to organize against police harms in Regina and to support Simon and others facing police violence and abuse.

This led to repeated interventions at the Board of Police Commissioners and at City Hall, media coverage of Simon’s assault in the Regina Leader-Post and Maclean’s, protests and marches on police headquarters, a mutual aid nighttime support team in the north side, and a grassroots community town hall and panel on policing. Police chief Troy Hagen was visibly shaken by the community pushback but maintained there was no problem with racism on his force (he retired shortly thereafter).

Simon’s racist assault that night ignited a resurgence of grassroots anti-police organizing in Regina, led in significant part by local activists connected to Briarpatch.

In 2016, then-Briarpatch board member Andrew Stevens was elected to Regina City Council, and in 2020 he was joined by former Briarpatch contributors Shanon Zachidniak, Dan LeBlanc, and Cheryl Stadnichuk in a slate of progressive councillors and school board trustees. Their four council votes were not enough to block yet another increase to the bloated Regina police budget in 2021, alas.

For any other current affairs magazine, this dedicated local organizing and political activity might be an unlikely offshoot, but for Briarpatch, nothing could be more true to form. Founded in Saskatoon in the early 1970s as a militant four-page anti-poverty newsletter, Briarpatch has been rooted in social movements (however much they wax and wane) ever since.

I started at Briarpatch in the spring of 2013, as the 40th anniversary issue was being finalized. I hadn’t grown up with Briarpatch on my radar in Alberta and I wasn’t even a print subscriber before becoming editor. It was an opportune time to join, as decades of back issues and archival photos were spread out in the offices and past staffers and contributors dropped by the office in preparation for the anniversary party.

Poring over the back issues, I was humbled and awed by the decades-long commitment not just to covering anti-poverty and labour struggles but anti-colonial Indigenous struggles in the North, prisoners’ struggles, disability justice, gay rights, international solidarity, and the systemic racism and brutality of municipal police and the RCMP.

A back-page commentary on the RCMP by Leanne McKay in the November 1977 issue is typical: “The highly glamourized and grossly inaccurate public image of the RCMP is one of an incorruptible force in constant battle against the forces of evil. In actuality, the RCMP is a power unto itself unaccountable to anyone and questioned by few. From this pinnacle of power the force has, from its inception, brutalized and terrorized the Indians [sic] and Metis of Canada’s northwest.”

From cover stories on a prison death and uprising at the Prince Albert Penitentiary (May 1976) to the Regina police canine unit (October 1982) to Indigenous child apprehension (January/February 1983), the publication has been a lodestar for under-reported liberation struggles.

As the late Clare Powell – former editor and a Briarpatch volunteer until his passing at age 81 – liked to say, “I’ve been disappointed by many politicians over the years, but I’ve never been disappointed by Briarpatch.” Indeed, under current editor Saima Desai, Briarpatch has not just continued but deepened and improved its legacy, bringing in Indigenous editors for the award-winning Land Back issue, imprisoned writers to make the Prison Abolition issue, and disabled organizers to edit the Disability Justice issue.

One can look back at 50 years of Briarpatch and despair that the same struggles and systemic injustices of the ’70s and ’80s are with us today. But that is not how I experienced the Briarpatch archives when I spent a few hours looking over back issues again last fall in preparation for these reflections. What I found instead – as I did 10 years ago when I joined – is an unbroken, undaunted, multi-generational lineage of social struggle and fiercely independent reporting that is rooted in love for one another and commitment to the greatest cause there is: a world free from settler-colonial capitalist domination.