“There was this community. There were people who came and hung around the office on a regular basis, or we met at the bar in the basement of the Hotel Saskatchewan, Formerly’s. That’s where a lot of stuff happened,” says Gary Robins.

Community is a thread that comes up again and again in the hours that I – Sara, a Briarpatch board member – spent with Robins and Edith Mountjoy, who both worked as Briarpatch staff members in the 1970s, in the living room of Mountjoy’s home. As we talked about the early days of the magazine, which Mountjoy once typed on a typewriter in an office with a dirt floor and a door that would freeze shut in winter, Robins’ and Mountjoy’s thoughts returned again and again to people they had known and worked alongside almost 50 years ago. The absence of Donna Pinay, a former editor of New Breed, whose health kept her from joining us, was felt keenly by both of them as they recounted the early years of the publications.

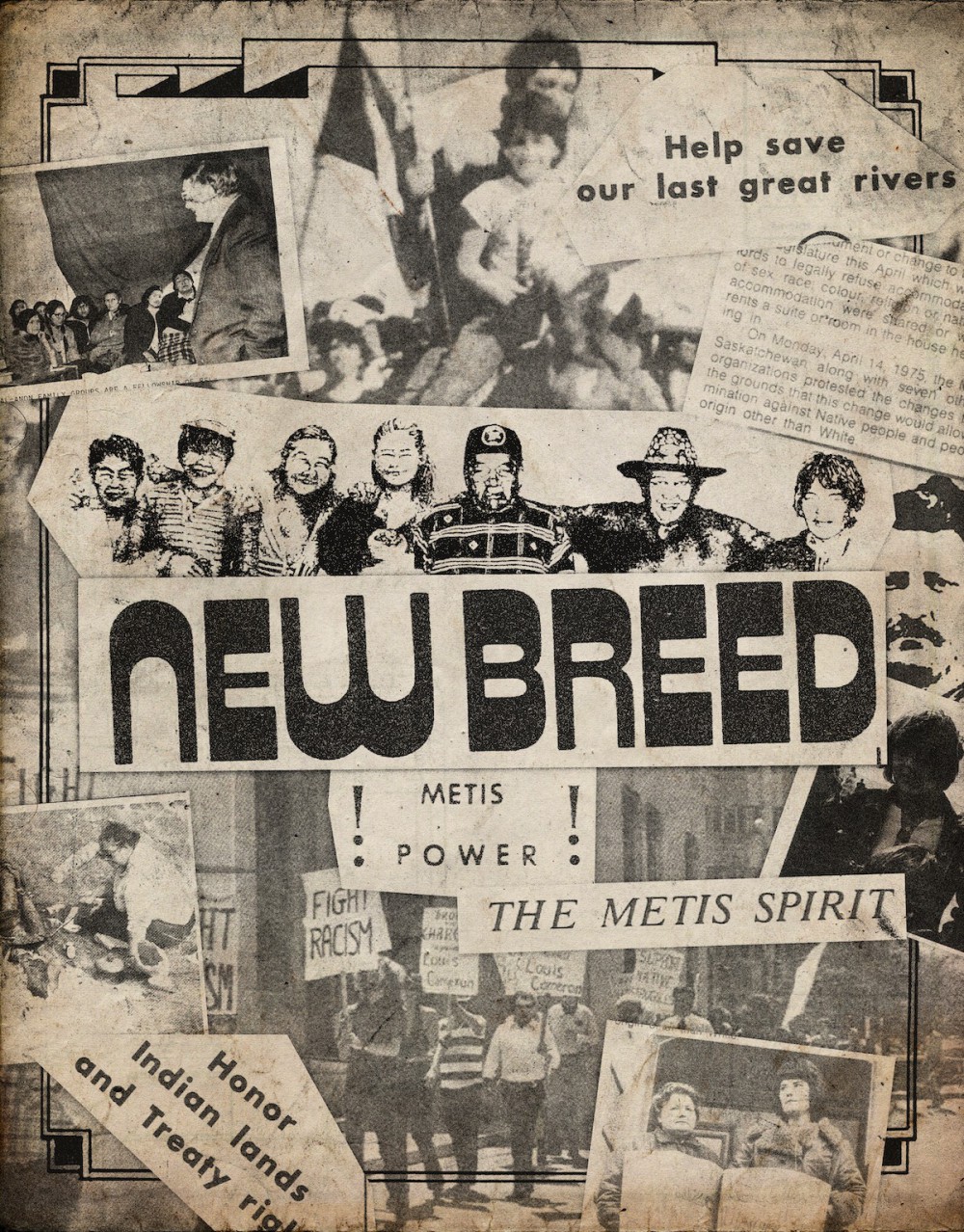

Briarpatch and New Breed both emerged in the context of late 1960s/early 1970s Saskatchewan. New Breed, one of the most radical Indigenous publications of its time, was co-founded and co-edited by Toni Durocher and Howard Adams, and it released its first issue in 1969. It was published by the Métis Society of Saskatchewan (MSS), the forebear of what is now the Métis Nation – Saskatchewan. While the two organizations are related, MSS included non-status First Nations people, even in positions of leadership, and was the result of the amalgamation in 1967 of two separate Métis groups, the Métis Association of Saskatchewan, which represented the interests of northern Métis, and the Métis Society of Saskatchewan, which represented the interests of southern Métis.

“This newspaper will try to link us together. Its policy is to get you involved as much as possible in the Métis and Indian movement."

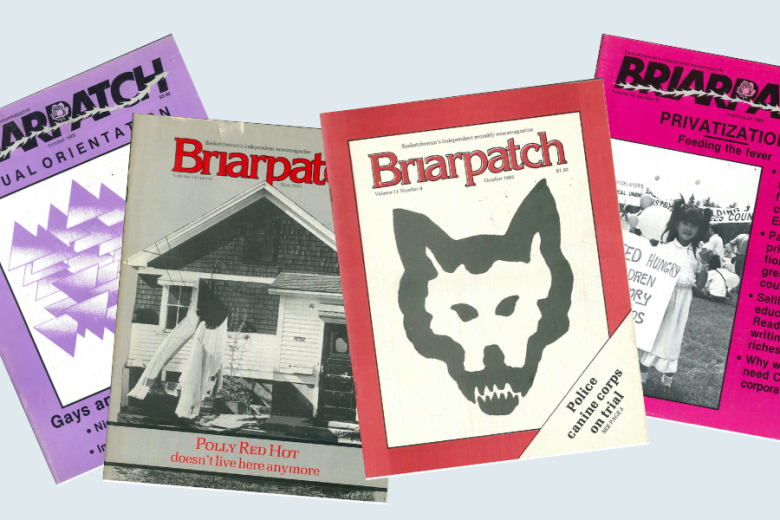

Briarpatch (then Briar Patch, a name that was both a dig at Larry Brierley, a social services administrator with whom Briar Patch staff were often at odds regarding funding, and a nod to other anti-poverty organizations in the U.S. which had adopted the same name) followed four years later, releasing its first issue – 10 pages, stapled in the corner, and published by the Unemployed Citizen’s Welfare Improvement Council – in August 1973.

The history of these two magazines – and particularly the ways they collaborated and supported each other – tells an important story about how the infrastructure of the left was built in Saskatchewan.

Reawakening Saskatchewan’s left

The 1960s and 1970s were a period of dramatic social and economic changes in the province. In the ’60s, according to Don Kossick, a Saskatchewan activist and organizer who was involved with Briarpatch from the beginning, student loans became easier to get (and, for a while, you could pay for part of your tuition in grain), and university was newly accessible for poor and working-class people. With a resurgent labour movement, radical activism took root on Saskatchewan campuses. Many of the students (and workers) at universities in the province made their way into labour and anti-war organizing and alternative media.

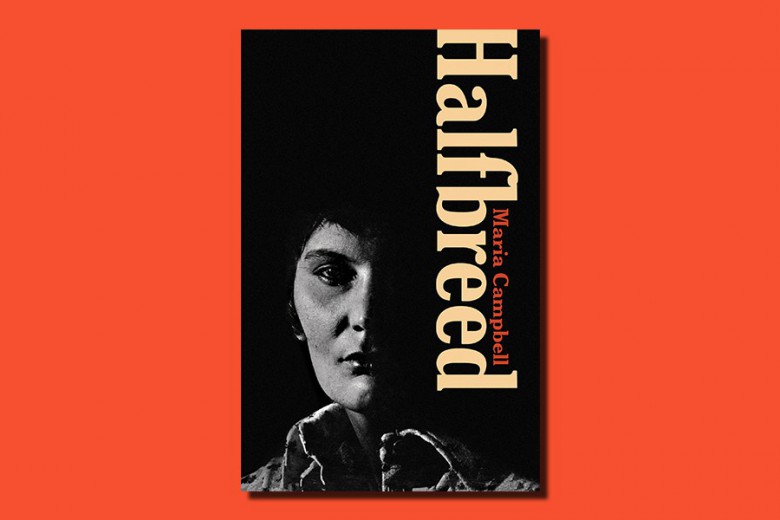

This occurred alongside a reawakening of Indigenous activism and media in North America, which, in Saskatchewan, included a renewed push for Métis rights and self-determination. New Breed’s co-founder, Howard Adams, was a radical socialist and a key leader and thinker in the Red Power movement. Born in 1921 in the Métis community of St. Louis and politicized by his experience growing up Métis in northern Saskatchewan, his fight for Indigenous liberation was grounded in Marxism and inspired, in part, by campus activism and the politics of Black radicals like Malcolm X.

At the same time, other radical Indigenous publications were springing up around the Native Alliance for Red Power, an organization formed by Indigenous women in 1967 in Vancouver, B.C. (Sḵwx̱wú7mesh, səlilwətaʔ, and xʷməθkʷəy̓əm territories). New Breed built relationships between them, often listing their names and addresses in its pages: the Native Press in Yellowknife (Somba K’e), Native People in Edmonton (amiskwaciwâskahikan), and Akwesasne Notes from the Cornwall Island Reserve in New York. The magazine also established ties abroad, republishing stories from Guatemala News.

“Media did play a key role in helping to keep things on track and keeping people organized in terms of knowing what they should be doing and what they could be supporting.”

“This newspaper will try to link us together,” read an editorial in New Breed’s first issue, published in November 1969. “Its policy is to get you involved as much as possible in the Métis and Indian movement. Therefore, we urge you to discuss the ideas raised in this paper with your brothers and sisters, and then organize for action.” It was a call that reflected a vision of alternative media as a way to both document and incite radical action, with reporters and contributors not passive observers but participants in the struggle for justice.

“A major tool for change was the alternative media,” says Kossick. “And those magazines did not exist in a vacuum; they linked back to the wider social movements.” Briarpatch and New Breed were part of a broader ecosystem of alternative media on the Prairies that included Prairie Fire, the Union Farmer, the Saskatonian, and Canadian Dimension, as well as a flourishing of university papers. “Media did play a key role in helping to keep things on track and keeping people organized in terms of knowing what they should be doing and what they could be supporting,” Kossick adds.

In a 2000 speech not long before his death at age 80, Adams spoke to the importance of the media in advancing the cause of organized Indigenous resistance. “We were fortunate in the ’60s and ’70s that the media [...] gave us favourable coverage. I think that was the one big thing that sort of made the success story we had,” he said. “We had a high profile, and we had a profile that was positive.”

Both Briarpatch and New Breed express a sense of journalism not as something belonging to a professional class of people, bringing information to the masses, but as a way of building community. The articles are written by and for the people most impacted by their contents. A 1970 issue of New Breed quotes the Canadian Daily Newspaper Publishers Association’s Code of Ethics: “[f]reedom of the press is not a special privilege of newspapers but derives from the foundational right of every person to have full and free access to facts in all matters.” Early issues of both publications share an eclectic mix of articles, poetry, and political cartoons.

New Breed also acted as a medium for sharing and rebuilding culture that colonialism had tried to destroy. The magazine published stories and recipes in Cree syllabics, including a regular Cree News column. It also shared letters from Indigenous diasporas in North America. “Bonjour-Tansi,” begins one letter from a university student who was raised by her white father and seeking to connect with her mother’s community. “Since I never knew my mother or grandmother I know little about being Indian, or what life is like on the reserve. [...] I am trying to regain a part of my heritage.”

In those days, Briarpatch often reported on Métis issues, decrying the theft and sale of Indigenous children, chronicling the fundraiser to build a new Métis centre in Lloydminster, and covering Métis Day celebrations at Île-à-la-Crosse. They frequently cross-published, with New Breed reprinting, among other things, Briarpatch’s articles on the violent use of police dogs and the apprehension of Indigenous children.

Assimilation or liberation

During the dawn of the Red Power movement, and when New Breed was first conceived, Saskatchewan was governed by Ross Thatcher’s Liberal Party. The early issues of the magazine chronicle his government’s contentious relationship with Indigenous Peoples and the Métis fight against government-imposed assimilation.

One report notes that Thatcher previously refused to meet with the Métis because they “never arranged a meeting with enough Half Breeds for him to meet,” adding that “it never enters his mind that a people who have been colonized for a century or more may have a little difficulty in raising funds necessary to attend a meeting.”

Thatcher had made addressing the deplorable living conditions of Indigenous people in Saskatchewan a key part of the government’s policy goals. This meant creating an Indian and Métis branch within the Department of Natural Resources and even going so far as to offer the position of deputy minister for Indian affairs to Adams, who refused, in 1968.

He was uninterested in ensuring that Métis people could sustain themselves on the land.

But Thatcher’s ideas for what “better conditions” looked like were profoundly colonial, centring almost entirely on job creation and “self-sufficiency,” with the intention of further dismantling Indigenous communities by “bring[ing] them where the jobs are.” His plans, like those of Tommy Douglas and Woodrow Lloyd before him, sent a grim message to Indigenous communities in the North: northern Saskatchewan is for industry, for uranium mining and settler fisheries. It is not for you.

Thatcher’s vision of “self-sufficiency” defined the term narrowly, as being able to pay for shelter and other basic necessities with income derived from wages or profits. He was uninterested in ensuring that Métis people could sustain themselves on the land – for example, he introduced regulations regarding the allowable size of mesh fishing nets that made it more difficult for fishers to sustain a living. “Now they try to starve us out,” one Métis fisher told the Toronto Daily Star in 1969. Thatcher was ill-equipped to meet the cultural resurgence in the province, at one point asking reporters, “What is their culture? Living in tents or dirty, filthy shacks on a reserve?”

The Thatcher Liberals were not the first government intent on assimilating Métis people in Saskatchewan. Even – perhaps especially – that sacred cow of the Saskatchewan left, the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (which would later become the NDP), had assimilationist policies that it imposed on Métis people, particularly those who lived in the North. This included forced relocations, where the CCF drew boundaries between prosperous white communities and impoverished Indigenous communities. In some cases, Métis people were loaded onto trains and moved 500 kilometres away. Saskatchewan’s unique position as a resource extraction colony for the East, and the CCF’s vision of itself as a crusader against that colonialism made it, according to Murray Dobbin in New Breed’s November/December 1978 issue, incapable of “seeing itself as the villain, the exploiter of another colonialism – the colonialism that degraded and impoverished the Metis people.” Dobbin added that when it came to racist attitudes, “the CCF was no better and in some ways worse than the old political parties.”

“We understood that political parties were intimately connected to the capitalist system that impoverished our people,” Howard Adams wrote in his book, A Tortured People: The Politics of Colonization. “For this reason, we believed that all parties, Conservatives, Liberals, and NDP, were incapable of making real changes.” In response, the Saskatchewan Native Action Committee decided to run an independent candidate in the 1968 federal election on a platform of self-determination and autonomous control of Indigenous lands. The candidate, Carole Lavallee, who alleged government interference in her campaign, lost to Progressive Conservative incumbent Bert Cadieu.

A “sense of solidarity”

The staff at Briarpatch were similarly critical of, and often opposed to, the politics of Saskatchewan’s nominally socialist NDP. “We just kind of gravitated toward each other,” says Robins of Briarpatch’s relationship with New Breed. Both publications recognized that even ostensibly progressive governments were not guaranteed to act in the best interests of the public, and what was needed was social movements. “To be able to get information out to people that they weren’t getting became a large part of our focus,” says Robins. “That’s part of trying to build a sense of movement. To show there are a number of organizations, and people who share those values, who feel that sense of solidarity with each other.”

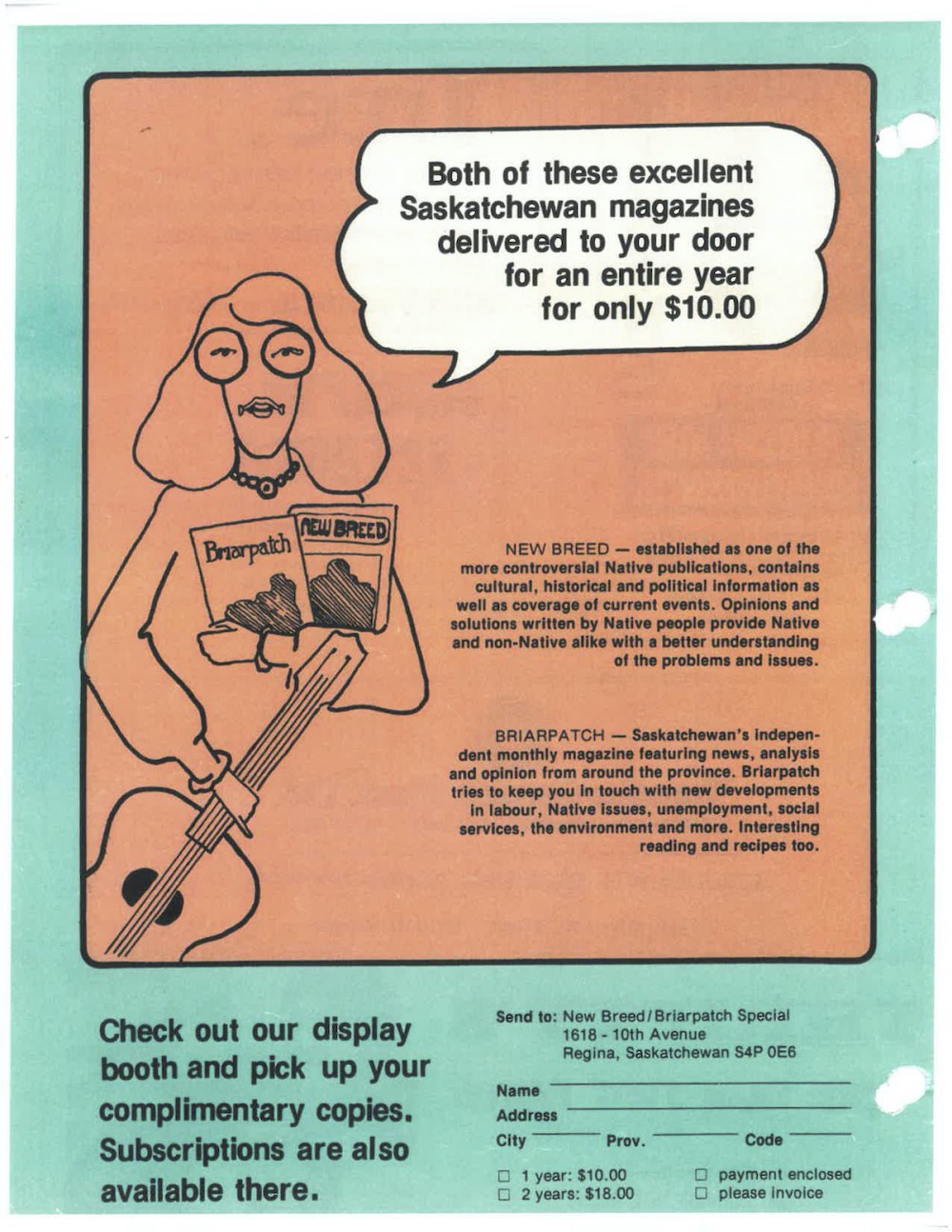

A joint Briarpatch-New Breed subscription ad from the back cover of the 1978 Regina Folk Fest program.

“Our collaborations with New Breed started over political discussions,” he says, but quickly moved to material support, like New Breed offering to let Briarpatch use their typesetting equipment, freeing Mountjoy from doing the work by hand. By the late 1970s, Briarpatch and New Breed were offering joint subscriptions – $10 for a year-long subscription to both magazines. “There was a real commonality there, and the work we did, we were all excited about it. And that’s what made it easy,” says Mountjoy. When Allan Blakeney’s NDP – angered by the magazine’s criticisms of uranium mining in the province’s north – cut Briarpatch’s $54,000 annual grant, New Breed helped keep Briarpatch alive. The funding was cut retroactively, Robins says, “so we were really out on a limb there for a while.” Being able to share resources with New Breed, which continued to receive grant funding from the provincial government, sustained Briarpatch while the magazine scrambled to build a donor base.

Both publications had, from the start, an explicit and deliberate focus on reaching prisoners. New Breed offered free subscriptions to all incarcerated people and some prisoners saw the magazine as a means of platforming their concerns about prison conditions. “I had high hopes that I would be allowed to have a temporary leave from the prison to get together with yourself, or someone from your staff to discuss certain concerns here,” wrote an anonymous prisoner to New Breed in 1983 about “cruel and unusual” conditions that were driving some prisoners to attempt suicide. “We are at a loss as of where to turn to for help, so it was decided to go public. Perhaps someone out there could write and inform our leader what steps to take.”

“We understood that political parties were intimately connected to the capitalist system that impoverished our people. For this reason, we believed that all parties, Conservatives, Liberals, and NDP, were incapable of making real changes.”

New Breed didn’t escape the attention of settler institutions, nor did it hold back criticisms. By February 1977, it was reporting that 23 RCMP detachments across Saskatchewan were requesting copies of the magazine. Editors welcomed the RCMP into the publication’s “wide readership,” stating that “we hope the NEW BREED will be of great assistance to you in establishing better communications with Native people [...] and a deeper insight into the whole area of racism as it exists in our society – why it exists and how it is kept in existence.”

In the following issue in April 1977, New Breed called for an inquiry into police brutality and the abuse of children in juvenile detention camps in the province’s north, along with a quote from Rod Durocher, vice-president of the Association of Métis and Non-Status Indians of Saskatchewan, where he stated that “the only solution for Native people is clearly to organize against police attacks and not to rely on the courts.”

The infrastructure of Saskatchewan’s left

New Breed’s archive is preserved online by the Gabriel Dumont Institute, which was described by New Breed upon its inception in 1980 as a place to “help the Native people find themselves so that they can walk with pride and dignity among their non-Native counterparts.” New Breed ceased publication in 2009.

Briarpatch, New Breed, and their other comrade publications in the ’70s and ’80s were foundational parts of what Alan Sears called “an infrastructure of dissent” – referenced by former Briarpatch editor Andrew Loewen in another Briarpatch article almost 10 years ago. When that infrastructure is weakened, Loewen writes, the left goes from being a major political force to struggling merely to stop the erosion of past gains. It’s a situation that’s all too familiar here in Saskatchewan, where the media is dominated by conservative talk radio, locked out workers are arrested by local cops, Crown corporations are sold off, and the government continues to pass legislation aimed at preserving settler hegemony and restricting Indigenous people’s movement on the land.

“We found a lot of kindred spirits on the staff of New Breed. The links and the connections came through individuals, the sort of people doing grassroots community organizing.”

Briarpatch and New Breed showed how to build community and capacity across diverse groups that, at first glance, may seem to have little in common, especially at a time when Indigenous–settler solidarity was uncommon enough that there was little language to describe it.

“It was a different social and political landscape,” Robins says. “The concept of settlers and allies was not part of the discussion.” But, he adds, “we found a lot of kindred spirits on the staff of New Breed. The links and the connections came through individuals, the sort of people doing grassroots community organizing.” Strength and solidarity within the alternative media brought many people under the same umbrella, creating links between radical movements that might have otherwise remained isolated.

“I think that’s part of the reflection of that time,” says Kossick. “Groups [were] willing to work together and walk along together. And I think we’ve lost a bit of that. We need to rebuild that.”