“I will build a great, great wall on our southern border, and I will have Mexico pay for that wall.”

When Donald Trump conjured this vision in his June 2015 presidential announcement speech, he established not just his political program’s agenda but also its genre: freewheeling, fact-agnostic fantasy. The liberal centre reacted with an appeal to data: the Washington Post reported, for instance, that in Trump’s first 100 days in office, he made no fewer than 492 misleading public claims. But fact-checking Trump has done little to check his power. Trumpian fantasy can’t be contested by appeals to realism, a strategy that requires apologetics for the violent reality of capitalism, imperialism, and structural oppression. Today’s left wins when we challenge the right’s cruel and exclusionary imagination with more just, more beautiful world-making projects of our own.

Such projects have, like Trump’s, already reached public consciousness from the top down, through politicians’ campaigns. Means of Production, a socialist film collective in Detroit, crafted video ads for U.S. representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and former congressional candidate Kaniela Ing’s electoral candidacies, exposing millions of viewers not to socialist ideas in the abstract but to concrete socialist visions of a good life. Momentum, the movement that formed in the U.K. in 2015 to support Jeremy Corbyn and a leftwards reorientation of the Labour Party, produced viral ads of a similar sort, framing socialist insights as both fresh and self-evident. Shifting the baseline of popular common sense, these short films helped make alternative futures more thinkable.

Unlike the narcotic concessions with which capitalism defangs rebellion – the pop song that calls you to live just for tonight, the latest wearable Apple device – these are pleasures with the capacity to mobilize.

Yet top-down efforts to shift ideology aren’t enough on their own. To be effective, they rely on many other imaginative projects undertaken in civil society: artists, writers, and other popular educators seeding left dreams in the soil of culture. Such workers challenge the ruling class’s hegemony from below. We do so by building pleasurable cultural alternatives to it, which serve as a pole of magnetism that can draw new comrades into organized material struggle. The pleasures in question are at once aesthetic, social, and intellectual – the delight of bonding over beauty with others who share your values, and with whom you can collectively develop concepts capable of explaining the deepest political sources of your suffering. Unlike the narcotic concessions with which capitalism defangs rebellion – the pop song that calls you to live just for tonight, the latest wearable Apple device – these are pleasures with the capacity to mobilize.

Today, they are perhaps most accessible online. Popular educators on the left have turned to platforms like YouTube in the hope of sharing their message with a mass audience. Long dominated by right-wing demagogues, YouTube now has a growing left flank, where Natalie Wynn’s ContraPoints channel may be the most celebrated. A trans woman who has urged her more than half a million subscribers to prepare for insurrection in the face of climate catastrophe, Wynn produces witty, irreverent, sumptuously art-designed spectacles of political persuasion. In moody coloured lighting and outfits always on point, she deftly dismantles bigots’ pseudo-rationality – taking on incels, the alt-right, and transphobes, among others. She’s far from alone in this sort of work: Patreon-funded online left content, including an assortment of socialist podcasts, has been gradually surfacing from the dark waters of the subcultural since the U.S. presidential election in 2016.

Mexie, for instance, an anti-capitalist YouTuber in Toronto, released her first video a few days after Trump’s inauguration and now broadcasts to 36,000 subscribers. Last November, she dedicated a video to exploring the role of speculative imagination on the left today. In it, she describes how, after many years of reading little besides theory, she became interested in visionary science fiction. “We’re great at dreaming up apocalypse, but what about utopia? And more than that – a viable utopia?” she tells me. “Visionary world-building in art and performance gives us a glimpse of what could be if we weren’t constrained by what is.”

That video, “Reclaiming Radical Creativity,” is inspired by Black feminist activist adrienne maree brown and her book Emergent Strategy. “We are living now inside the imagination of people who thought economic disparity and environmental destruction were acceptable costs for their power,” writes brown, in a passage Mexie discusses in her video. “It is our right and responsibility to write ourselves into the future. All organizing is science fiction,” brown continues. Mexie knows that political struggle will always involve a high degree of contingency, that no utopian blueprint can be sketched definitively by any one person. “But that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t dream it,” she says, shouldn’t propose positive visions of the future to our frightened neighbours, who might otherwise seek solace and order in the distorted meaning-making of the right.

“I mean, creativity has been so co-opted under capitalism. […] Creativity is Silicon Valley making smaller and smaller phones.”

Like brown, Mexie recognizes that the imagination of a better world must be connected to practical modes of struggling for it. “Essentially I hope my work will educate, agitate, and lead to organizing,” she says. She’s also careful to distinguish the way she speaks of creativity and imagination from how capitalism appropriates that language. “I mean, creativity has been so co-opted under capitalism. […] Creativity is Silicon Valley making smaller and smaller phones.” But she insists that such co-optation doesn’t lessen the importance of creativity as a revolutionary force: a faculty of articulate dreaming that can be wielded by the left to activate new organizers, as well as to broaden the bases of social support for existing organizing.

One way to tackle the problem of stimulating creativity and imagination for emancipatory aims – not just as buzzwords that artwash capitalism’s violence – is by forging relationships between artists and political activists, Toronto-based theatre-maker Thomas McKechnie suggests. His most recent production was presented with the support of the United Steelworkers, the Canadian Union of Postal Workers, and the Socialist Project, organizations associated more closely with working people’s material struggles than with the development of art. A celebration of the 1919 Winnipeg General Strike called Remembering the Winnipeg General, McKechnie’s play cast its gaze not forward to possible futures, but backward to radical histories able to anticipate those futures.

McKechnie, who is also currently involved in organizing Foodora couriers in Toronto, considered it crucial that socialist organizers have a visible presence at his production. He set up a space just outside the performance venue where groups like the Industrial Workers of the World (which represents self-employed and freelance workers, a category that includes many arts workers) could table. “My hope,” McKechnie says, “[was] to stir up the revolutionary feeling in the audience and then immediately send them to some place they [could] use that feeling.”

This kind of direct collaboration between artists and activists is rare in Canada. The liberal culture industry commodifies certain marketable forms of left-ish politics, but generally it declines to bring its consumers into relationship with radical organizing – including not only militant trade unions and groups with the word “socialist” in their name, but also, for instance, those that foreground Indigenous land rights, Black liberation, or sex worker self-determination.

“As activists, [we’re] still trying to push the mainstream needle to the left in Canada, away from reformists.”

That’s a huge missed opportunity, McKechnie argues. “We need to get away from dead space [for hosting art] and move to spaces where life is happening. We need to take shows to picket lines and encampments. We need to take them to Queen’s Park and the offices of TransCanada […] We know how to use aesthetics to communicate. [We need to] start communicating a lot louder and a lot more publicly.”

Approached strategically and critically, mainstream liberal cultural institutions can have a reach that’s useful for radical culture builders. Just as Mexie has taken to Google-owned YouTube to access a wide audience, risking corporate censorship when anti-imperialist tags or keywords (#handsoffvenezuela, #freepalestine, even #neoconservative) appear in her videos’ descriptions, so McKechnie stages some of his plays at venues that don’t fully align with his politics. “I do the work that the bourgeois theatres will produce with the bourgeois theatres,” he says, “and I do the spicier political work outside of those institutions.” But insofar as Mexie and McKechnie aim to dismantle the capitalist ideology that underwrites those institutions, they occupy them as benevolent saboteurs.

There’s also something to be said for artists skipping the liberal institutions altogether and instead building anti-capitalist culture in spaces dedicated to anti-capitalist politics. After Ontario’s provincial election last year brought the Conservatives to power, the Fight for $15 and Fairness and the Ontario Federation of Labour organized the large Rally For Decent Work in Toronto. Visible at the rally were climate justice groups, public health advocates, rank-and-file members of many unions – and Mohammad Ali, who performs under the extremely good stage name the Socialist Vocalist. A hip-hop artist who’s a fixture at local protests, Ali more recently took part in the Ontario Coalition Against Poverty’s disruption of “Dinner With A View,” a ritzy outdoor dining experience hosted under Toronto’s Gardiner Expressway, close to where a homeless camp had just been demolished.

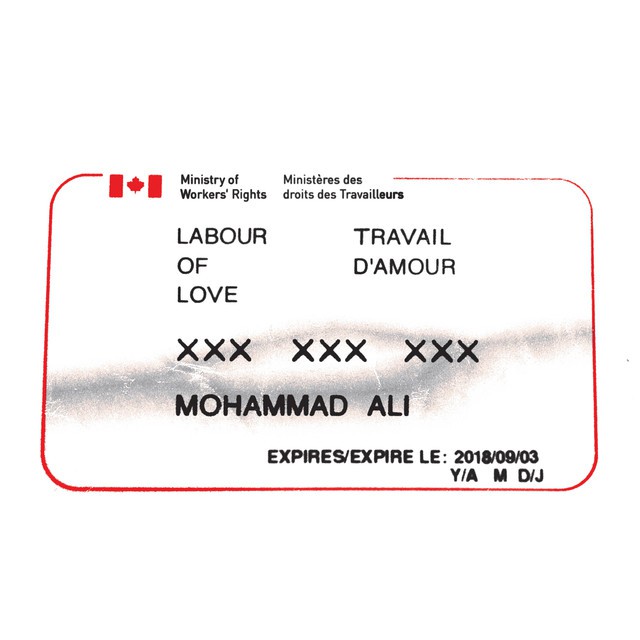

Ali’s new album, Labour of Love, speaks to “the need for a radical and truly progressive agenda centred around addressing economic inequalities, democratic freedom, and equity for marginalized groups,” he says. “As activists, [we’re] still trying to push the mainstream needle to the left in Canada, away from reformists.” There are indications that such tectonics of ideology may be on the move. Not long ago, his riffs – My boss at the cottage talking ’bout austerity/Lounging on Muskoka chairs, he ain’t trying to share with me – represented an unusual lyrical niche, capital-p Political. Now, under Doug Ford’s breakneck austerity, he says they’re “just common discourse.” To be sure, discourse changes because social circumstances do: language like “the 1 per cent and the 99 per cent,” for instance, named a growing public awareness of vast wealth inequality that existed before those terms were popularized. But the language also made a contribution: it transformed that diffuse awareness into a tool that could be used to rally people for more organized politics, like Bernie Sanders’ first presidential primary campaign. As changing realities shift political common sense, the work of culture building can help consolidate the shift – and make sense of it.

“We need to get away from dead space [for hosting art] and move to spaces where life is happening. We need to take shows to picket lines and encampments. We need to take them to Queen’s Park and the offices of TransCanada.”

Such a sense-making project is also a base-building project, a way of attracting large numbers of people to a social movement’s struggle. “A mass of Canadians are ready for a progressive shift to the left,” Ali says. His work is “unapologetically socialist […] while also engaging that [potential] mass audience.” This approach to base building is not top-down, not about petitioning major institutions for access to a platform, but rather about artists throwing their lot in with grassroots social forces that are themselves trying to scale up. In this model, the artist has a mass base because and when the movement does. The artist’s and the movement’s interests are interwoven. This is one way, perhaps, that an artist can today stand meaningfully for liberatory politics and against capitalism, even if a total escape from capitalist relations has yet to become available to anyone.

In 1930, German socialist Ernst Bloch expressed a fear that fascism, not content with its earthly expansionist aspirations, was also colonizing the terrain of utopia. The left, he warned, was “not keeping watch on what is happening to […] utopian trends. The Nazis are already occupying this territory, and it will be an important one.” Whatever other comparisons between our moment and Bloch’s may suggest themselves, one simple continuity seems clear: the stuff of politics is not just need, but also wish. So let us dream, and build the political power necessary to realize those dreams, lest we be condemned to live in the dreams of fascists – and so that we may at last escape the dream of a merchant, grasping and craven, proud of his whiteness and mean to his wife, in which we’ve been caught for the past four hundred years.

_780_520_90_s_c1.jpg)