Some of the most profound understandings about our world emerge from ordinary people coming together and working for change. They come from Indigenous peoples holding the line on their land against state and corporate assaults on their sovereignty. They come from within the organized movements of small farmers – many of them women – against land and water grabs, industrial agriculture, and the commodification of nature. They come from migrant and immigrant workers – often deemed unorganizable by trade unions – fighting for labour and immigration justice. These struggles are incubators for ideas that can not only enrich our analysis of the world, but also help us to think through, in our own lives and locations, the possibilities and ways to change it.

In order to get a handle on what it actually takes to organize for change, we must take seriously the learning and the production of knowledge that occurs in the intellectual work of daily struggles, as people come together to discuss problems and injustices, debate strategies, and act. All too easily, people’s work and actions can get cut up and compartmentalized: protesters protest, researchers research, educators educate, organizers organize. When we overlook the fact that everyone has the capacity to learn and reflect in the course of struggles for change, we are left with simplistic “paint by numbers” accounts of movements and activism that focus on great individuals, charismatic leaders, clever slogans, and professional spokespeople, and that mistakenly attribute the rise of social struggles and movements to social media.

British feminist adult educator Jane Thompson argues that the purpose of knowledge has to be more than an individualistic solution to personal disadvantage. As she puts it: “Social change, liberation … will be achieved only by collective as distinct to individual responses to oppression.”

Amnesia in organizing

Sociologist and activist Gary Kinsman, concerned about how the radical roots of movements and community resistance get replaced with more “respectable,” liberal versions of history, reminds us of the need to overcome the “social organization of forgetting.” Drawing a curtain over the critical histories of people’s struggles in favour of more simplified versions is quite consistent with the kinds of neoliberal tellings of history that privilege individuals’ achievements in place of the rich, nuanced, and often dangerous and difficult stories of the struggles of many ordinary people. We can see this through the ways in which the struggle against apartheid in South Africa – which involved millions of people organizing, with different liberation movements and political tendencies – has often been reduced to the life and words of Nelson Mandela. We see it in the dominant focus on middle-class male leadership like Gandhi and Nehru in the freedom struggle in India, and the erasure or downplaying of a wide range of popular resistance, including women’s struggles, workers’ strikes and peasant revolts, and revolutionary, anti-imperialist, and sometimes armed movements. Or we are fed techno-utopian claims that the Quebec student strike happened because of social media, and that the Internet defeated the Multilateral Agreement on Investment in the late 1990s – however, both of these assertions simplistically overlook all of the organizing that took place to build movements from the ground up, so to speak.

The work of small groups of people battling away and gaining ground, usually in long-haul organizing, are often edited out of our collective memories. For example, the international anti-apartheid movement and today’s Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) activism was built in Canada and many other countries by small groups of Palestine solidarity activists who worked for years before larger organizations and institutions took action.

Records and memories

The histories of people’s struggles for change are themselves repositories of ideas, debates, and practices that can offer invaluable conceptual and practical resources. But the extent to which organizers and activists in contemporary social movements, political organizations, communities, and popular struggles engage with earlier movement histories, memories, and ideas in the course of their organizing ranges widely.

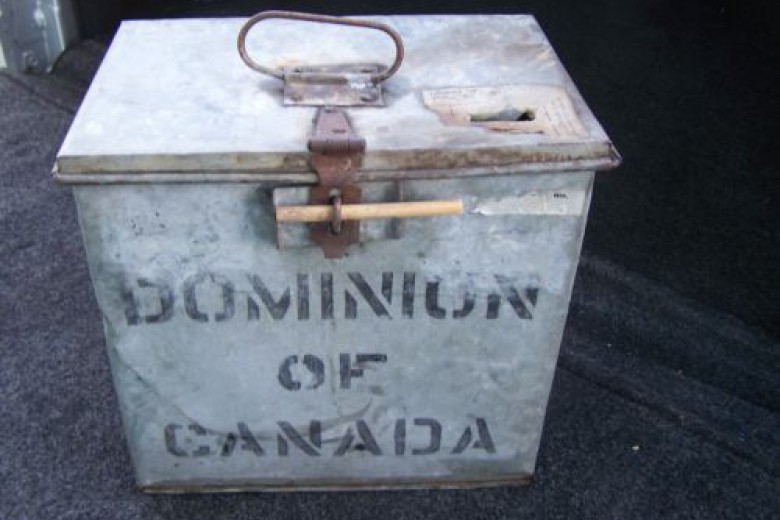

Resource constraints and other competing priorities mean that activists and movements are not always able to focus on preserving their own histories, or passing on and critically engaging with them. As British scholar and activist Anandi Ramamurthy notes, records might be lost when organizations break up, participants become disillusioned, or people move offices and homes. Many times, state repression factors into the destruction or loss of such materials. Moreover, organizers and movements are often focused on effecting immediate change rather than preserving records or drawing lessons from their activities for the next generation.

Recycling or recovering relevant ideas and concepts from earlier struggles requires us to be wary of constructing imagined histories and continuities with the past; we should also avoid trying to formulaically replicate past victories. On the other hand, we must be wary of the tendency to automatically avoid old tactics in new contexts simply because they didn’t work in other situations.

We cannot afford the costs of historical and social amnesia for contemporary and future struggles, for risk of losing the thread and texture of what it takes to bring about social change, and being left with a version of history that glosses over or ignores the significance of behind-the-scenes organizing. Such amnesia can paper over the conflicts, tensions, and power dynamics that have been part of these organizing efforts and from which we can also learn.

Overcoming brains v. brawn

As historian E.P. Thompson reminds us, ordinary people make their own history. I think we have to dig into the relationship between the informal, incidental learning that happens in the often mundane work of organizing, as well as the more intentional internal education work done in communities in struggle and within activism, such as workshops and programs of political education. Australian adult educator Griff Foley explains that much learning in social action is informal and incidental: “it is tacit, embedded in action and is often not recognised as learning.” Moreover, learning in social movements is complicated and contradictory. It can both reproduce the status quo, dominant positions, and ideas, and also generate what Foley calls “recognitions which enable people to critique and challenge the existing order.” This makes such learning “difficult, ambiguous and contested,” he writes. Yet both forms of learning tend to get pushed out of focus in most descriptions and accounts of movements – so, in order to be able to retain and integrate the valuable lessons from this work, it requires that we be engaged in, and able to reflect on, action.

The organizing, learning, or ideas produced in social movement struggles shouldn’t be romanticized, but many of us underestimate or dismiss the capacity of ordinary people – not least, those who are socially and economically marginalized – to think and theorize in the course of, and in relation to, struggles for justice. Some of the ideas they share take us beyond the common sense horizons of possibility that many have accepted as the only way to think. A contemporary example of this can be seen as migrant and immigrant workers organize outside of traditional union forms, in organizations such as Montreal’s Immigrant Workers Centre, which challenge us to rethink where and how working-class movements might be reinvented or rebuilt.

There’s also a tendency for people to measure the short-term success or visible impact of movements at the expense of appreciating the broader and deeper significance of processes that take much longer to bear fruit and may not be easy to map. Without daily struggles, larger systemic change cannot come about. And it is in these daily, local struggles that people build analysis, skills, strategies, and a base needed for longer-term, broader change. Adult education scholar Paula Allman insists on the significance of these struggles for reform, “whether these pertain to issues emanating from the shop floor, the community, the environment or any other site where the ramifications of capitalism are experienced…. These struggles are some of the most important sites in which critical education can and must take place. Moreover, if this critical education takes place within changed relations, people will be transforming not only their consciousness but their subjectivity and sensibility as well.”

It can be instructive and sobering to reflect on how ideas and causes once viewed as radical or subversive, such as the right of women to vote and stand for electoral office, can become mainstream, while once-mainstream ideas, such as forms of social ownership, are reshaped as extreme. Claims about the apparent newness of some contemporary challenges, more recent mobilizations and forms of activism can sometimes pull us away from thinking deeply about continuities in the social, political, and economic systems within which people struggle. The present day can often be disconnected from its histories, including concepts and lessons from earlier struggles, in ways that essentially see all collective struggles everywhere as failures and openly or implicitly accept that there is no real alternative to capitalism as we lurch from one crisis to another at a planetary level.

I am conscious of the significance of intergenerational learning and of personally straddling, on one hand, a critical period between politics, education, and organizing traditions forged in the Cold War era (not to mention insights from older forms of insurgent internationalisms, and anti-colonial resistance and liberation struggles), and, on the other hand, more recent kinds of communication and political engagement that sometimes seem a little too uncritical in their utopian claims about digital media producing and shaping apparently new, leaderless, horizontal movements (from Occupy to uprisings in Egypt and elsewhere in the Middle East). Moreover, I am aware of a swell of entrepreneurial, individualistic, professionalized approaches to social change, even as they invoke language and concepts about “community” or “the collective.” The Quebec student strike – which was built by careful organizing rather than through Facebook – showed that a new generation of student activists (whom many people dismissed as entitled, self-absorbed youth) have things to teach us about collective action. Yet we cannot ignore that free-market capitalism has affected collective action, resulting in the atomization of individuals, the promotion of a kind of social change and environmental entrepreneurialism, and fierce competition to brand and claim ownership over progressive ideas and issues.

Who speaks?

Like many others, I have experienced conflicts within organizations and coalitions committed to working for peace and justice, with people who routinely ignored or dismissed racism, sexism, and colonialism as being unrelated to the “real issue” as defined by the dominant cliques within those groups. I’ve also experienced how anti-colonial and anti-imperialist perspectives have often been shut down in these spaces. Ego and personality politics seemed as embedded in many of these networks as in the world that we were supposed to be trying to transform. Quite early on in my political activist experience, I learned that there is not necessarily a unified “we” or “us” in “the movement.” I began to critically examine the claims of organizations that purport to work for a better world in relation to their actual practices. I also learned that it can be difficult to challenge assumptions and power dynamics within many organizations and groups. How much dissent is tolerated within avowedly radical or critical political places/groups? How do we challenge internal policing of dissent within activist/progressive spaces? How much self-criticism, debate, or discussion is deemed acceptable (and by whom) in different activist contexts? I believe it’s also important to think about how much change is propelled by tendencies or ideas that are seen as marginal to the dominant structures of movements (such as anti-racist currents within labour and feminist movements), and yet have helped form the foundations for future struggles of, for instance, migrant and other racialized workers.

Then there is the way in which people fall into thinking about “movement intellectuals,” spokespeople, and representatives. Many movement and NGO networks and activist groups produce a kind of “high priesthood” of experts, people who speak and put forward ideas and positions, but who are not necessarily doing so in tandem with, or with accountability to, a community or social base. One consequence of this is that it can divert attention from the fact that it is often the ordinary people in struggles who create knowledge and ideas: much of the intellectual labour of organizing does not take place through panels of experts, media conferences, and statements; it is worked out in the course of action. Perhaps some of the most significant ideas arise from conflicts and tensions within larger organizing efforts. For example, within and at the fringes of coalitions and alliances, sharp analysis and sophisticated understandings have emerged about the roles of many NGOs in supporting capitalist interests. Although it is not a given, people often learn far more profoundly about the power and interests of the state through direct confrontation with its security forces (such as the police and intelligence agencies) than a workshop or written account could convey.

Perhaps, then, these fabricated separations between roles are less about a division of labour between “ideas people” and “movement activists,” but rather reflect the alienation of many ordinary people from their intellectual labour, the ideas and visions produced in collective action. Is knowledge only valued if it is produced in certain institutional settings by people with particular qualifications or professional status? We might ask this question of social movements and other forms of activism just as we pose it to academia – we cannot just assume people don’t know anything and need an educational liberator or activist saviour to lead them.

There is often a tension between the professionalized actors who speak at the conferences, workshops or panel sessions and write the NGO, community organization or activist group statements, policy analysis documents and critiques, and those who do the often mundane work of organizing people and trying to build and sustain what sociologist and activist Alan Sears terms the “infrastructures of dissent” – “the means through which activists develop political communities capable of learning, communicating, and mobilizing together.”

This kind of division is problematic. Even within many of these networks and organizations, the benefit of learning by doing is often undervalued and ignored. I get a strong sense of disjuncture when elite forms of knowledge are elevated as “expert” and “authoritative” by the same organizations and movements that promote democracy and the equal valuing of different knowledge traditions. As well, those of us who can convincingly talk and write in ways that mesh with academically and other officially sanctioned forms are often reified as experts. This seems to reflect Foley’s view that movements and community organizing can reproduce status quo power relationships. NGOs and activist groups often define issues – and themselves – in a narrow, compartmentalized way, and in so doing set parameters for campaigns and political action.

I remain somewhat agnostic about organizational forms and their relations to learning and producing knowledge that is useful and relevant to struggles for progressive social change.

There is no neat recipe for cooking up the social, political, and economic conditions for radical learning and knowledge production. Power, history, and context are central considerations. But as Black U.S. historian Robin Kelley suggests, it is “in the poetics of struggle and lived experience, in the utterances of ordinary folk, in the cultural products of social movements, in the reflections of activists, we discover the many different cognitive maps of the future, of the world not yet born.”