The townsfolk were all stunned and abuzz. Shaking their heads and trying to find words for what Old Farmer Jakob had done. Recounting the accumulation of community knowledge; spinning out old yarns; reliving memories; sifting for some reason, some motive, some sign.

Saying all the while, “But he was such an honest man!”

They knew that he came from overseas and that all he knew was digging holes.

The first two he dug were for his brothers two weeks after armistice. They were torn apart in a flash and a shower of soil when their plow overturned a live shell sleeping in the family fields.

With his young wife, Ana, he had left on the next boat for the land of opportunity.

Jakob had calculating eyes that could divine the machinery working below the surface of life’s situations. His stubborn will stood firm in the face of hard truths. He was the kind of man who shouted to prove his confidence, but more often than not he was silent in thought.

Ana was a hale and hearty woman with clever hands that spun life’s wool into workable thread. With energy and wit that knit together their new marriage, she was the kind of woman who sang often and clearly to anyone with ears to listen. She smiled because sometimes it was all she could do.

Their love was deep and warm and quiet.

The two had claimed a plot of dusty turf some decades past as part of a church settlement deal. They tore the soil while it slept, and come spring it awoke, batting a green eyelash. They mostly sold the tears on those lashes to the grocer, Herbias J. Corningstone, a man who insisted his middle initial be included at every mention. His twine was constantly unravelling so that he sputtered when he spoke and fretted with his fingers, but he was always ready with a firm handshake and a fleet-footed quip from behind his big, black cash register.

Jakob and Ana’s cornucopia spilled into baskets on market day, where the townsfolk advanced with hungry families at home.

Jakob and Ana’s cracked lips rose in thin grins.

Their family swelled with children who loved their mother’s bedtime stories. When she read, the words came alive from the big book that seemed to hold every story ever told. Chores with their hard-working father reddened their hands and levelled their heads. Sons and daughters both civil and roguish grew to be men, women, and more. Some took up school, some married, and they all moved away. All the while, the tractors gritted their bits and squinted their eyes ever forward, lugging leather, metal, and wood through the fragrant earth.

After the war, it all seemed like a song of hope and plenty. It was a time of experimentation and abundance. Business boomed. And farming changed fast along with family and town.

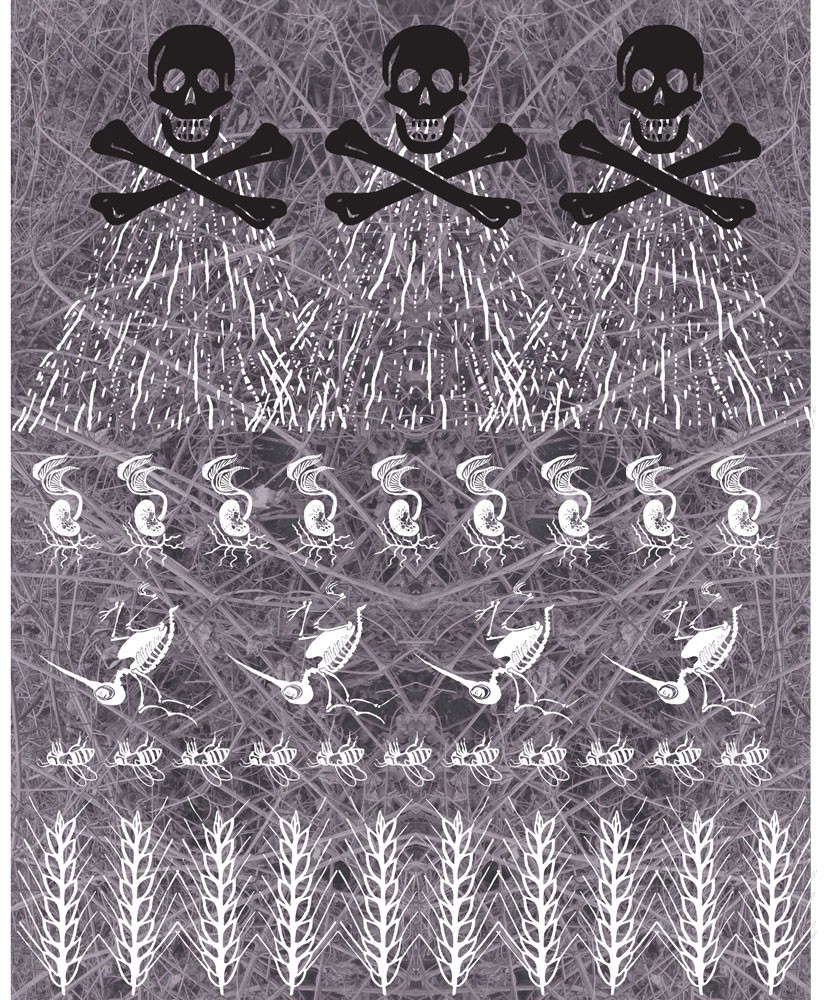

Jakob moved along with the times. He arranged his old equipment in their red-painted hospice and bought a big, new tractor, seeder, and thresher. He purchased different laboratory seeds, pesticides, and fertilizers – the works. They kept a few animals for winter meat, and Ana refused to give up her cherished garden, but Jakob set his calculator eyes on wheat and wheat alone. He had to. Other farmers had green dripping from their hands, stuffed into wallets and banks, and he wasn’t about to be left behind.

Every morning Ana sang Jakob awake in tune with the coffee kettle in the kitchen. Sometimes, as he grumbled good-naturedly over his toast, she went out to fuel the tractor or fill the sprayer with the sweet-smelling, blue-green liquid that kept their crop clean. On those days, as she sang in the garden among her stacks of purple and white carrots, her rows of crisp peas and piles of outcast dandelions, the saccharine aroma lingered and clung about her, inviting a quiet worry to knit her brow.

Now and again they went into town to meet with their financier.

The bank was as bright and hard as the grinning banker, who spoke to Jakob about global surplus, bilateral trade agreements, the wheat board, and agricultural subsidies. Beneath a trim toothbrush moustache, the banker’s silver tongue danced and spun. As he spoke of ups and downs and flows and policies, Jakob stared out the window and silently tallied the bustle of town. Ana tried to smile through her disquiet.

Their plants pierced the sky and leaned with the weight of an ample harvest. But wheat prices dropped in this time of surplus, and hungry bank accounts gnawed at the townsfolk.

Like many other farmers in the flatlands, Jakob met with a company man and had his wheat shipped to the same place the money came from – Lord only knows where. He signed a document agreeing to send his crops off when the truck came, no buts about it. He agreed to buy his seed from the company man. And chemicals, too. All under contract. He liked that. He felt catered to. Looked after.

Herbias J. Corningstone’s country market went out of business, overrun by a stark food warehouse with well-lit aisles and special deals and fancy labels. They sold all manner of tools and clothing and foodstuffs at rock-bottom prices. No one really knew what came of the flighty Herbias J. He disappeared. Most suspected he just moved away of his own accord. Ana wasn’t so sure.

Ana often went out to the fading old barn, thronged with nesting swallows, to sit with the cantankerous old iron ox that now rusted and filled with mice and spiders. Pondering, she looked down at her hands – hands traced in turquoise in the fading evening light.

And then one day, the banker gave them the news. Payments had begun to outstrip revenue. Like many family farmers, Jakob and Ana were digging a different hole now. A seed planted in this hole eats down to nothing – it doesn’t sprout.

Day in, day out, they struggled. Tried to make the farm pay. But soon enough, the company man phoned, speaking in the language of contract about crop projections and moneys overdue. Old Jakob scribbled numbers on bills and in ledgers. He scribbled on the mortgage papers, too, and the banker gathered them up in eager hands. Ana still sang her old songs in the garden, but her voice quavered in a faint and unfamiliar key.

The aging couple grew a plentiful harvest. But it grew short of targets. So they grew short of coin and short of food. Then they were short of health and short of time. But Old Ana still smiled. She smiled and swelled with hope and with cancer, singing softly to herself in her vibrant garden. She sang among the thick scarlet runner beans, flowers whirring with hummingbirds, rows of crisp cabbage heads, and a small forest of purple-crowned chives.

But her own vigour failed.

While his wife quietly ebbed away in a quilted room, Old Jakob toiled on. He toiled for her medicine, toiled for her food, and he toiled for her doctors. He worked his bones into the soil. The sprinklers wept. The hogs lamented. The weather vane twisted in the prairie wind. Jakob harvested teardrop kernels from acres of golden lashes.

And when Ana quietly slipped away, Jakob dug another hole as his children headed home.

After the funeral service and the hubbub of well-wishers and mourners, his children left once more to tend to their faraway lives. Jakob felt a numbness creeping in, and he paced about the empty house to chase it away. He stopped and stood for a long time at the bookshelf in the living room to look at the old photographs, to lose himself in the memories and wonder at the way everything had grown and moved and changed so fast.

He pulled out the old tome of fairy tales that was Ana’s favourite, and the children’s too. Tucking it under his arm, he walked out to the old, washed-out barn. He sat down again in the high metal seat atop the ruins of his tractor, the mice and swallows and spiders gathering all around.

He opened the book to a marked page. And there he saw a picture of Snow White, pale as Ana in her deathly sleep, a poisoned apple tumbling from her outstretched palm. Something twisted, snapped inside him. He closed his eyes and fought the grief and guilt and rage that threatened to swallow him whole.

The banker phoned to offer his condolences, but also to remind him of debts owed. Old Jakob proved his modesty and resolved to accept his fate.

Well after the roosters crowed at sunrise, the company man and the grinning banker arrived. The suits wore their men well. They were two peas in a pod, with civil and unyielding briefcase hands. They wrinkled their noses at the pigpen and knocked on the door. Old Jakob invited them in for breakfast and business.

Mugs of bitter coffee clinked. Jakob swallowed and watched the suits do the same. They didn’t notice the blue-green stain on Ana’s fine white china. Jakob’s thin lips shook. His eyes flared with doubt and triumph. The air in the room shifted and fled, and a cry of sorrow caught in his burning throat.

And so Old Jakob dug his final holes.