On the first warm, sunny spring day, beekeepers across Canada head to their apiaries, hoping to hear the familiar hum of buzzing bees emerging after a long winter. Instead, this year, many beekeepers were greeted by dead hives, devoid of life, save the occasional mouse.

In the past three decades, beekeepers have seen unprecedented bee colony losses. Although the numbers fluctuate from year to year, it’s become common for an average of 30 per cent of bee colonies to die during the winter – a number already too high to be sustainable. In 2022, the situation was even worse: in Ontario, Manitoba, and Alberta the early numbers of overwintering colony loss have been as high as 80 per cent, with an average of 40 to 45 per cent. Although we don’t yet fully understand the causes of colony loss, the main one seems to be the varroa mite – a tiny red-brown mite that plagues honeybees, spreading a variety of viruses and other pathogens – whose populations boomed during the long, hot summer of 2021.

Bees are the most prolific and efficient of animal pollinators, pollinating about 80 per cent of the Earth’s plants. Not only do high honeybee losses spell disaster for the agricultural crops they work to pollinate – like canola, apples, and squash – they also imply sickness and death in the 800-plus species of wild, native bees across Canada. A loss of bees, especially those wild bees whose populations are not managed by humans, will be catastrophic for most ecosystems.

It will require a sustained, grassroots movement that emphasizes solidarity between the fractured groups that share some critiques of capitalist agriculture.

The call has been heard across the globe, taken up by almost every big environmental NGO, to “save the bees.” Even large multinational food corporations have joined the chorus. Beginning in 2016, Cheerios – owned by General Mills, the American agrifood giant – removed Buzz the Bee from their packaging to draw attention to bee losses. On their #BringBacktheBees campaign website, people could request free wildflower seeds to plant in their backyards.

But what the Cheerios campaign and other corporate initiatives do not acknowledge is that the loss of honeybee colonies and declining populations of some native bee species are largely driven by the capitalist agricultural system and the monocultures it creates – a system that these large agrifood corporations helped create and are invested in maintaining.

The truth is that we cannot save the bees without ending capitalist agriculture. It will require a sustained, grassroots movement that emphasizes solidarity between the fractured groups that share some critiques of capitalist agriculture: farmers and farm workers; livestock farmers and animal rights activists; and, in the case of bees, beekeepers and native bee advocates.

Capitalist agriculture and landscapes of scarcity

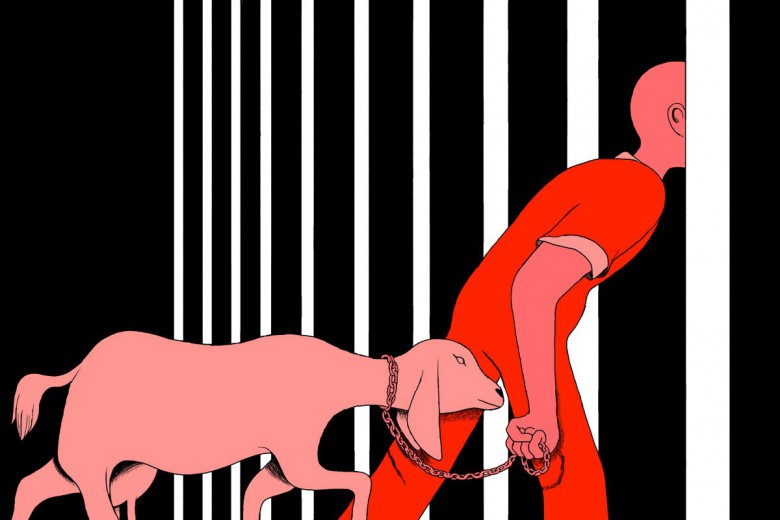

Not every agricultural operation that exists within the global capitalist system can be characterized as capitalist agriculture. There are many forms of subsistence, smallholder agricultural operations that are only partially – and in some cases, involuntarily – integrated into the global capitalist system. I define capitalist agriculture as agriculture focused on accumulating wealth and capital by simplifying and standardizing landscapes and the bodies of farmed animals. Capitalist agriculture turns food into commodities that are part of a global system of exchange. When it comes to bees, this looks like the sale of close to 1.8 million tonnes of honey each year. Honeybees have also become workers within the landscapes of capitalist agriculture, pollinating millions of acres of monocultured crops.

One of the most harmful aspects of capitalist agriculture is its reliance on monocultures. In a monoculture landscape, one or two dominant crops are grown over a large area, or one species of animal is farmed, bred to grow bigger and faster. These landscapes may seem abundant in one sense – they conjure images of fields of corn or soy, stretching as far as the eye can see – but they are scarce in terms of good sources of forage for bees and many other animals. They also lack nesting locations and materials for wild, native bees. And honeybees, who are often put to work in monocultures of crops that need animal pollination, may face poor nutrition in these homogenous landscapes.

Richie Nimmo, a sociologist who studies human–non-human relationships, describes the commercial beekeeping industry as the “apis-industrial complex” to highlight how it is fully embedded in the global capitalist agricultural system to the detriment of honeybees and many beekeepers.

Although migratory commercial beekeeping exists across the world, it is perhaps most entrenched in the United States, where beekeepers cross the country to pollinate almonds, blueberries, cranberries, and other high-value crops. The almond industry in California is the most extreme example of this, as 1.2 million acres of almond trees need cross-pollination in the blooming season in February. In 2020, over 88 per cent of all the honeybee colonies in the United States, amounting to about 2.4 million colonies, were brought to the almond-growing regions in California for about six weeks of pollination.

Not only does this type of commercial beekeeping aid in the rapid spread of pests and pathogens among honeybees, it further entrenches capitalist agriculture. Richie Nimmo, a sociologist who studies human–non-human relationships, describes the commercial beekeeping industry as the “apis-industrial complex” to highlight how it is fully embedded in the global capitalist agricultural system to the detriment of honeybees and many beekeepers.

“Ontario is a terrifying model of monoculture,” explains Luc Peters, the owner of Humble Bee, a beekeeping operation in Hamilton, Ontario. “There’s even some beekeeping operations that operate as a monocultural industrial farm. I think that’s damaging to the honeybees themselves. If you dump 2,000 beehive colonies in one spot that’s going to be harmful for the environment, much like [exclusively] growing corn on 100 acres.”

Systemic pesticides and corporate beewashing

A key way in which monocultures are created and maintained is through the widespread use of pesticides, including insecticides, herbicides, and fungicides. Although all pesticides may negatively impact bees, one class of insecticides, neonicotinoid pesticides, is particularly harmful to bees. Neonicotinoids are the most used class of pesticides in the world, deployed on most non-organic commercial crops, including corn, soy, and canola, some of the most prolific crops on Earth. Although agrochemical corporations try to control and confuse the discourse about the harms of systemic pesticides, there is a large and growing body of evidence that indicates that these pesticides may cause a variety of ill effects in bees. Occasionally, this may include directly poisoning bees – but it also may include perhaps more harmful, sub-lethal effects from repeated exposure, such as impeding foraging and overwintering behaviours; decreasing queen bee health and colony growth; and stressing bees’ immune systems.

Over the past five years, the top six agrochemical and seed corporations, sometimes referred to as the “Big 6,” have merged, morphing into four powerful multinational corporations that dominate the agrochemical and seed markets: Bayer-Monsanto, DuPont, ChemChina-Syngenta, and BASF. These corporations exercise immense influence over government policy and international agreements about pesticides, engaging in aggressive lobbying and, sometimes, taking legal action against attempts to restrict neonicotinoids. In 2013, Bayer unsuccessfully took the European Commission to court after the EU introduced restrictions on some types of neonicotinoid pesticides.

Agrochemical corporations and agricultural industry groups have launched several “beewashing” campaigns that attempt to convince the public that capitalist agriculture can be bee-friendly. The Cheerios #BringBacktheBees campaign is one; another is the “educational” website Bees Matter, which is a project of a conglomerate of agrochemical corporations and industry groups, including CropLife Canada, Bayer CropScience, and Syngenta. Bees Matter’s “learning centre” features op-eds opposing neonicotinoid bans, including “Good news: there is no honeybee crisis,” and “Bee deaths reversal: as evidence point[s] away from neonics as driver, pressure builds to rethink ban.” The website is slated to close on June 30, 2022.

Agrochemical corporations and agricultural industry groups have launched several “beewashing” campaigns that attempt to convince the public that capitalist agriculture can be bee-friendly.

Despite agrochemical corporations’ immense power, environmental activists have waged campaigns against neonicotinoid pesticides with some success. In Ontario, a partial restriction on neonicotinoid usage – albeit one that was weakened by the government’s insistence on heavily consulting with agrochemical corporations – was enacted by the Liberal government in 2015, and it took full effect in 2017. But in 2019, Doug Ford’s conservative government passed Bill 132, ominously called the Better for People, Smarter for Business Act, and the partial pesticide ban was substantially weakened to the point that it is now essentially voluntary.

But stronger neonicotinoid bans can and have been won. The European Union banned five types of neonicotinoid pesticides in 2018, after almost five million people signed a petition calling for the ban. The EU took a “precautionary principle” stance, which means that although there was still some uncertainty about the link between neonicotinoids and bee deaths, the EU proactively banned the pesticides to avoid potentially irreversible harm while also calling for more scientific research into their effect on bees. While there are some significant weaknesses in the EU neonicotinoid ban, it has held relatively strong against the attempts of agrochemical corporations to dismantle it.

Honeybees: sick yet numerous

Honeybees are native to parts of Asia, Africa, and Europe, where they were domesticated thousands of years ago. Due to their role as producers of honey and, later, pollinators, they have been spread by beekeepers to every continent on Earth except Antarctica. While they are sometimes popularly discussed as if they are wild animals, they are, in fact, highly managed by humans and deeply embedded in global agriculture systems. And yet while these semi-domesticated animals are plentiful, they are vulnerable. It is important to recall the work of animal rights advocates here: it is possible for an animal species or breed to be numerous yet sickly. One only needs to think about battery cage chickens to understand that high population numbers does not mean a population is flourishing or healthy.

Aside from environmental stressors of pesticides and inadequate forage, honeybees face high levels of pests and pathogens. The most destructive one is the varroa mite, which sucks the fat of larvae and adult bees and, in doing so, spreads a variety of viruses between colonies and apiaries. Since arriving in North America in the late 1980s, likely through the global trade of honeybees, the varroa mite is widely assumed to affect the vast majority of honeybee colonies on the continent and to be the cause of most colony deaths, especially when combined with environmental stressors. Beekeepers use a variety of strategies to deal with mites, from cultural controls to organic acids to miticides, but as the heavy overwintering loss in 2021–2022 demonstrates, they don’t always work.

One only needs to think about battery cage chickens to understand that high population numbers does not mean a population is flourishing or healthy.

For a beekeeper, the loss of a honeybee colony can be extremely upsetting. I have felt this sting myself, as a small-scale beekeeper, sad my colonies didn’t make it and confused about what caused their death: viruses and environmental stressors cannot be seen on the bodies of dead honeybees when trying to autopsy a hive. For beekeepers trying to make a living from beekeeping, large overwintering losses can drive them out of beekeeping. But the problems caused by sickly honeybees go beyond honeybees and beekeepers. There is widespread concern among native bee scientists and advocates about the impact of sickly honeybees on populations of wild, native bees.

Honeybees are highly managed but they are only semi-domesticated. They remain genetically quite close to their wild counterparts, especially compared to other farmed animals, and they have a high level of agency over their own lives and their movement across landscapes. They usually forage within three kilometres of their hives, but can go up to 12 kilometres if they cannot find adequate forage. They swarm (when half the colony and the old queen leave to start a new colony) as part of colony reproduction, and they can go feral, forming wild colonies outside of human management. It is this lack of human control over honeybees that makes them an object of concern for native bee advocates. Honeybee viruses – such as deformed wing virus, which makes bees unable to fly – may be able to transfer from sickly honeybees to native, wild bees. Although the evidence on the harm caused by this viral transfer is inconclusive, it could be devasting to wild populations of bees. Plus, nutrient-deficient honeybees in landscapes of scarcity may over-forage nectar and pollen, starving wild bees.

“No one is really looking after the native bees. They’re suffering from the same issues the honeybees are suffering from."

As Peters points out, “Honeybees can be a great [basis for] advocacy. They’re like the panda of the insect world. People love them. People like honey and we can use that to bring up these other issues.” But, he adds, “No one is really looking after the native bees. They’re suffering from the same issues the honeybees are suffering from. I think it’s important, if we sell bees, to talk about what’s harming the bees and not sugar-coat it.”

Some beekeepers, like Peters, opt out of being part of the apis-industrial complex, engaging in more bee-centred practices such as using organic treatments for mites and other pests; cultivating a mindful approach to hive checks; and keeping beehives stationary in abundant landscapes such as city rooftops, urban farms, and organic, diversified rural farms. Beekeepers engaged in bee-centred beekeeping practices are more easily aligned with small-scale and organic farmers, environmentalists, and native bee advocates than with the largest commercial, migratory beekeeper operations.

Interspecies alliances to confront capitalist agriculture

Small-scale beekeepers can be part of a post-capitalist agricultural system in which the simplified and standardized landscapes of capitalist agriculture are replaced with vibrant agroecological landscapes where people, domesticated animals, and wild animals thrive. If capitalist agriculture manufactures landscapes of scarcity, a post-capitalist agricultural system can and should create landscapes of abundance.

A compelling vison of post-capitalist agriculture is one in which billions of small farmers grow food using ecological, democratic, and collective methods to meet the needs of the people in their bioregions and beyond. In this vision, agriculture will be integrated within ecosystems in ways that nurture biodiversity and make space for the “wild”; the labour of farmers and farm workers will be highly valued; and the relationship humans have with domesticated animals will be radically altered. Beekeepers will be free to use practices based on care and connection rather than efficiency and profit, producing honey and beeswax for their communities without exploiting the bodies and labour of honeybees. Spaces for wild, native bees will be created in urban and rural areas with ample sources of nectar, pollen, nesting materials, and nesting sites.

In some ways, non-human animals and plants are also part of the struggle: bees swarm, farmed animals escape, native bees and other wild animals make nests where they please, and weedy plants disrupt monocultured fields and lawns.

Confronting and eventually dismantling capitalist agriculture may seem like an insurmountable, even impossible, challenge. However, there are many movements that exist throughout the world that are already working on it: small-scale farmer and peasant struggles; urban agriculture advocacy; environmentalists and ecologists focused on pesticides and biodiversity loss; Indigenous communities demanding land back; beekeepers concerned about honeybees and their livelihoods; farm workers fighting for rights as workers and citizens; animal rights advocates confronting the commodification of the bodies and lives of animals; and more. In some ways, non-human animals and plants are also part of the struggle: bees swarm, farmed animals escape, native bees and other wild animals make nests where they please, and weedy plants disrupt monocultured fields and lawns.

The struggle against capitalist agriculture will be strengthened considerably if these movements form interspecies alliances based on solidarity across difference. Building this alliance will require difficult conversations and necessitate compromises and considerable changes in practices, tactics, and strategies. While this process will not be easy, it is urgently necessary. Post-capitalist agricultural systems based on nurturing landscapes of abundance are possible – and in the face of declining bee health, biodiversity loss, and climate chaos, they may be the only way to create a flourishing future for humans and for bees of all species.