In an old Chevy pickup, we slowly make our way down the trail that connects the main road to the lake ahead of us. The leaves are a riot of bright yellows, tangerines, and burgundies. In the passenger seat sits Amos, a Dena Elder, who was born well before this road – or any other road in his country – was even built. Amos remembers travelling to this lake by dog team as a young boy with his mom and dad, visiting friends and family who were staying here. He remembers travelling the river in a moosehide boat and trading beaver furs for bullets, flour, and sugar at the old post that has since burned to ash. He remembers sitting inside a wall tent on the shore during the long winter nights in the 1930s and ’40s, listening to stories the Elders told in the language of this place, speaking of a time before the world flooded thousands of years ago. He has come here for most of his 90-some years.

As we approach the waterfront, his energy changes. We see a number of trucks parked along the shore, some tents, a few trailers. Beer cans lie on the ground around the fire. Eight moose hang from trees and poles around the camps along the shore. Eight moose. We do not recognize anyone from the groups. While our licence plates indicate that we are from the territory, here by the lake, these people are strangers. We stop the truck, get out, and no one acknowledges Amos. Nobody approaches him to offer him tea or some of the meat that they have harvested from his Peoples’ land. After a tense minute of observation, Amos looks at us and suggests, in his humble and peaceful Dena way, that we return home to Tū Łidlini. Despite his calm tone and confident demeanour, there is pain in his eyes.

The territory of the Kaska Nation spreads across so-called northern British Columbia, the Yukon, and the Northwest Territories. It’s a land of mountain ranges and interconnected river systems. Wide river valleys are criss-crossed by trails deeply beaten down by the annual trek of caribou, moose, and wolves; the bones of this vast country carved by millennia of movement.

“Our country is big,” says Kaska Dena Elder Mary Maje. “Before the settlers came here, our Dena tracks were all over the place, you know.”

The Ross River Dena Council (RRDC), part of the Kaska Nation, is located in Tū Łī́dlini or Ross River, Yukon. The RRDC represents the northern third of Kaska country, in the eastern part of the Yukon.

“Our country is big,” says Kaska Dena Elder Mary Maje. “Before the settlers came here, our Dena tracks were all over the place, you know.”

The current village of Ross River, home to around 300 people (roughly 85 per cent of whom are Dena), is at the end of a long winding road that turns from pavement to dirt as it passes Faro, Yukon. Sitting on a bed of thawing permafrost and in the long shadow of the hill to the south, this is not the traditional village site. In the mid-20th century, as a means to force the Kaska Dena under state control, the Canadian government physically moved the village from the sunny north side of the confluence of the Ross and Pelly rivers to the south side of the Pelly River, 500 metres downstream. Most of the village residents were out on their traplines at the time. They came home to find their houses had been moved; some followed skid marks to their new location.

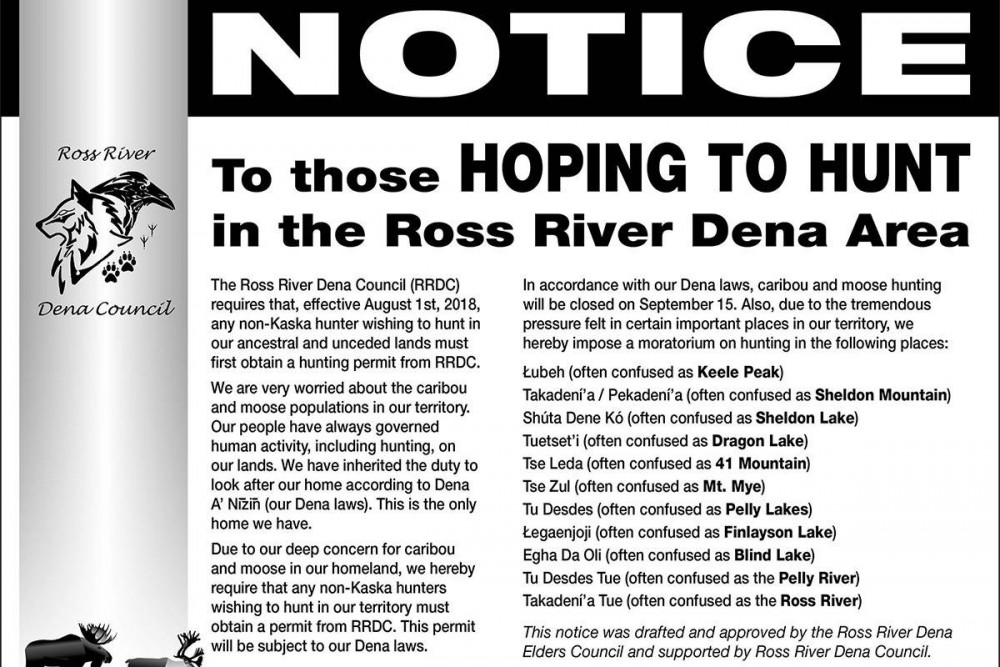

Guided by their inherent right to govern their territory, the RRDC enacted a hunting permit system during the 2018, 2019, and 2021 hunting seasons, requiring non-Kaska hunters to obtain a permit from the RRDC. In doing so, they amplified a complex and contentious dispute between the Kaska and settler governments about the land and jurisdiction. The Kaska abide by a complex relational system of ethics, laws, and governance that guide their interactions with their country; the settler state, conversely, draws upon colonial logics of rights, recognition, property, and resource management.

Certainty

To understand the RRDC’s hunting permit system and its fallout, we must first examine its context: the modern treaty process.

Today, 11 of the 14 First Nations in the Yukon have signed self-government and comprehensive land claims agreements (also known as final agreements or modern treaties) through the comprehensive land claims process (CLCP). The CLCP emerged in the 1970s after the famous Calder case in which the Supreme Court recognized the legal existence of Aboriginal Title to land, which meant that the federal government had to address the extinguishment of Aboriginal Title and engage First Nations that had not signed historical treaties or had their rights acknowledged through any other legal means.

Designed to address the “unfinished business of treaty-making in Canada,” the federal government insists that comprehensive land claims “remain a critical piece in achieving lasting certainty and true reconciliation.” By 1993, the Council for Yukon Indians (now the Council of Yukon First Nations), the Yukon government, and the Government of Canada ratified the Umbrella Final Agreement (UFA), the framework that guides modern treaty-making in the Yukon. In the decade that followed, 11 Yukon First Nations signed final and self-government agreements under it. But the Kaska Nation has strongly and consistently opposed the UFA since its ratification.

The Indian Act ceases to apply to Indigenous Nations that have signed final and self-government agreements, turning those formerly sovereign nations into a fourth level of government, subject to the authority of Canadian federal, provincial or territorial, and municipal governments.

In 2001, the federal government presented the Kaska Nation with an ultimatum: complete a comprehensive land claim under the Yukon-wide UFA framework by June, or negotiations will end and the Kaska will be without a modern treaty. Guided by the staunch refusal of their Elders, who rooted their position in Dena ethics and laws, the Kaska Dena leaders at the time said no, and the RRDC, like other Kaska, has held its position since.

Modern treaties grant Indigenous Peoples ownership over a small percentage of their Traditional Territory (called settlement lands). The 11 Yukon First Nations that have signed final agreements have settlement lands where their title remains; 8.6 per cent of Yukon’s land mass is settlement land. Non-settlement land is Crown land, where Aboriginal Title has been extinguished and ownership converted to the Crown. Under the UFA, Yukon First Nations have access to self-government agreements that give the First Nation jurisdiction and law-making powers on their settlement lands and allow them to co-manage the resources on non-settlement lands with the territorial government. The Indian Act ceases to apply to Indigenous Nations that have signed final and self-government agreements, turning those formerly sovereign nations into a fourth level of government, subject to the authority of Canadian federal, provincial or territorial, and municipal governments.

Guided by the staunch refusal of their Elders, who rooted their position in Dena ethics and laws, the Kaska Dena leaders at the time said no, and the RRDC, like other Kaska, has held its position since.

Despite the benefits that modern treaties offer, the process is fundamentally at odds with a Kaska Dena worldview. As RRDC Elders like the late Charlie Dick explained, one important rationale for the rejection of the UFA is that within a Kaska Dena worldview, people cannot own land and therefore cannot sell or trade it. For Charlie, who played an active part in the Kaska’s land claims discussions leading up to the 2001 decision, land is not “property” that can be divided and managed based on arbitrary lines drawn on a map.

Another point of contention for RRDC Elders and leaders, both 20 years ago and today, is the inclusion of the “certainty clause” within modern treaties that requires First Nations to “cede, release, and surrender” their rights and title to the Crown in exchange for monetary compensation and a new package of rights and jurisdiction. For the Kaska, at stake is the loss of their inherent responsibility to ensure the continuation and protection of Dena Kēyeh and the Kaska way of life. According to Kaska Dena Elder Dorothy Smith, “We are the caretakers of all of our country. It’s big. And because we don’t have a land claim, settlers shouldn’t be the boss of any of it.”

As “non-signers” of the UFA, however, the RRDC continues to be governed under the Indian Act. Yet, their Aboriginal Title has not been extinguished, nor have they negotiated a new package of rights through a modern treaty. As such, according to the late Steve Walsh, former lawyer for the RRDC, 23 per cent of the Yukon and 10 per cent of B.C. is unceded Kaska country.

Dena and state laws

The Ross River Dena, like other Kaska, govern their relations with non-humans according to “Dena kʼéh gusʼān” or “Dena ā́ nézen,” which loosely translate to “Dena laws.” A few of the central tenets of these laws include a strong responsibility to share with one another; to show deep respect for the land, including all the beings that are part of it, and to one another; and to follow certain teachings, passed down for generations, about the treatment of the land and animals.

“Even though the government doesn’t recognize our ways, we have to stay with Dena kʼéh gusʼān and maintain our own code that applies to all of our lands,” says Elder Mary Maje.

Dena kʼéh gusʼān sets out the way humans should live alongside non-human relations, like the sheep, caribou, and moose that share Kaska lands. Caribou and moose are not resources to Kaska Dena; they are non-human relations with their own long histories in Dena Kēyeh. They are critical actors in Kaska Dena culture, society, and governance.

Through generations of direct observation and oral history, the Kaska Dena know that the number of some of these animals is declining. Throughout the territorial north, Indigenous Knowledge Holders and wildlife biologists agree that, with a few exceptions, most every caribou herd is in danger today. Herd numbers have suffered from climate change, habitat destruction through resource extraction, and unsustainable hunting practices. Despite the last 50 to 80 years of calculated settler approaches to caribou management, the federal government’s Species At Risk Act currently classifies boreal caribou as “threatened” and many other mountain caribou herds as “of special concern” or “at risk.”

Caribou and moose are not resources to Kaska Dena; they are non-human relations with their own long histories in Dena Kēyeh. They are critical actors in Kaska Dena culture, society, and governance.

The Kaska do not trust the Yukon government when it comes to caring for the animals that live alongside them. As Ross River Dena land steward Norman Sterriah says, settlers “brought a management system from the old country that doesn’t work here; it’s not from here.” The Yukon governs human-animal relations through the Yukon Wildlife Act, a piece of legislation stemming from the UFA, of which a central objective is “to preserve and enhance the renewable resources economy.” The UFA categorizes beings like fish, caribou, and moose as “resources.” As such, animals are understood to exist for human use and capitalist gain. Under the UFA, wildlife is co-managed by Yukon First Nations with final agreements and the Yukon government. Both parties appoint representatives to sit on boards and committees – however, on Crown land, the Yukon government has the final decision-making authority on wildlife management laws, including the issuance of hunting permits.

Many Kaska Elders believe that the Yukon’s wildlife laws are unsustainable and disrespectful. For example, says Sterriah, Kaska Dena leaders and land stewards have for many years voiced their emphatic opposition to the practice of radio collaring, in which animals are tranquilized with darts shot from planes, collared, and then tracked and monitored remotely by biologists in Whitehorse and Ottawa. Similar to other Western wildlife management practices like catch-and-release fishing, radio collaring violates Dena ethics of consent. Kaska Dena Elders teach that it is ā́ʼíi/doola – taboo or forbidden – to force anything upon another individual’s body.

The Yukon government also allows for hunting male (bull) caribou and moose well after they go into “the rut,” the time of year when they begin to move around and breed. The Kaska Dena have strongly opposed hunting bulls in the rut, as the animals stop eating and their bodies are pumped with hormones – sometimes making the meat basically inedible. Large bull caribou and ram sheep also lead the herds to food and safety, and large bull moose mate with numerous female moose (called cows) each season, which helps keep population numbers up. Understanding their importance, Kaska Dena ethics advise against selectively harvesting large bulls.

“Even though the government doesn’t recognize our ways, we have to stay with Dena kʼéh gusʼān and maintain our own code that applies to all of our lands,” says Elder Mary Maje.

Six hunting outfitters operate in the RRDC’s part of Kaska country, and it is the Yukon government that determines their quotas and their hunting season – not the Kaska. Escorted by outfitters, hunters in search of the most impressive trophies seek out the biggest bulls. This leaves the rest of the herd without guidance and doesn’t allow for the biggest and healthiest animals to pass on their genes.

On top of that, the Yukon government controls hunting licences for resident Yukoners. As per the Wildlife Act, the only areas in the Yukon that non-Indigenous hunters are required to obtain Indigenous consent to hunt within are the settlement lands of a First Nation that are covered by a final agreement.

In the case of the Kaska, where there is no final agreement and no settlement lands, the Yukon government treats all of their territory as Crown land, imposing rules and regulations from the Wildlife Act that directly violate the ethics of Dena kʼéh gusʼān and inviting settlers to hunt on Kaska territory without Kaska consent.

According to Sterriah, caring for the land and animals is a collective Kaska practice based on generations of observation. “We had these old-time practices from way back when – beginning of time – about not over-harvesting and habitat management and all kinds of things,” he explains. “The people back then, they gather together and say, ‘My traditional land use area is getting pretty skinny on caribou’ [...] and they come back [together] and say, ‘What should we do?’ They probably say, ‘Leave it alone for a few years [...] until the numbers come back up.’ In the meantime, no one don’t go hunting unless you really need it.”

Sterriah remembers his grandparents saying “you gotta stay away from those places” – it is ā́ʼíi to go there. But many non-Kaska hunters don’t follow these teachings.

“The emphasis was on need,” he says. “When I was growing up, that’s what they tell me: ‘Take what you need.’ That’s what they say. Sharing was a big part of that too. When somebody gets something, everyone gets a piece, you know?”

He says the Kaska Dena must now be allowed to uphold their inherited responsibility. “The land stewards, these are the people that [...] need to be back out there,” he explains. “Their task was taken away by governments. The governments now say, ‘This is how we’re going to do things now.’”

The trip we made with Amos, when we found his childhood hunting grounds overrun by unfamiliar hunters, with eight moose strung up, wasn’t a lone incident. During the Yukon’s hunting season, the Ross River Dena area now floods with outsiders. Big-game outfitters fly foreign hunters into special Kaska Dena hunting areas: from Pelly Lakes to Macmillan Pass. The many roads that were built through Kaska country to facilitate resource extraction are now trafficked by non-Kaska hunters from the Yukon, B.C., and the Northwest Territories.

Important animal habitats like mineral licks and calving grounds are being hit hard. Sterriah remembers his grandparents saying “you gotta stay away from those places” – it is ā́ʼíi to go there. But many non-Kaska hunters don’t follow these teachings. Their ATVs carve out new trail networks, making it easier to access these once-protected areas. Dena hunters are crowded out of their family harvesting places and are forced to go into the winter without meat.

Gary Ladue, a Kaska hunter and former Ross River Dena Council councillor, skins kedā (a moose) just outside of the town of Ross River.

The Kaska and the courts

In an effort to uphold their inherent responsibility and to enact their ethics and laws, the Kaska have engaged the Yukon government in negotiations – to no avail. The Yukon government continues to impose the UFA on the RRDC despite the fact that they have neither signed a final agreement nor given consent.

Pursuing an alternate route, in 2016 the RRDC filed a lawsuit against the Yukon government over the government’s unilateral issuance of hunting licences in the Ross River part of Kaska territory. RRDC argued that since Kaska rights and title have not been extinguished, the Yukon government should be bound to a higher standard of consultation and accommodation than what is laid out in the UFA – following instead, for example, the standards set out in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, which call for Indigenous nations’ free, prior, and informed consent to laws and policies enacted within their Traditional Territories.

However, the judge ruled that the RRDC “does not have a right to veto any development or impose a duty to agree or require that RRDC consents to any developments in the Ross River Area.” In other words, according to the courts, since the RRDC has rejected a modern treaty, which is a mechanism for recognizing Aboriginal Rights and Title, the governments of Yukon and Canada should still have jurisdiction over their land.

Effectively, despite 150 years of settler colonial policies aimed at removing Indigenous Peoples from their land, to prove their title they must demonstrate that they still use every corner of it (continuous) and that they have never shared it with their neighbours (exclusive).

To understand the nuances of the Yukon Supreme Court’s judgement, it helps to turn to the precedent set by Tsilhqot’in Nation v. British Columbia (2014) on establishing Aboriginal Title. In Tsilhqot’in Nation, Aboriginal Title includes “the right to possess the land” and “the right to pro-actively use and manage the land.” However, this case also stipulates that First Nations must prove, among other things, “continuous” and “exclusive” “use and occupancy” of the land in order to prove that they have Aboriginal Title over said land. Effectively, despite 150 years of settler colonial policies aimed at removing Indigenous Peoples from their land, to prove their title they must demonstrate that they still use every corner of it (continuous) and that they have never shared it with their neighbours (exclusive).

Tsilhqot’in Nation outlines a multi-stage process for seeking legal recognition of Aboriginal Title. According to the precedent set in that case, the courts have claimed that the RRDC is at the beginning stage of this process. Their options are to continue to seek recognition of their Aboriginal Rights and Title through the courts or through a comprehensive land claim. Until such point, Kaska Aboriginal Title essentially has not been proven through the eyes of Canada’s settler colonial legal system.

The RRDC hunting permit

Engaging the Canadian state through the courts or the CLCP has profound philosophical implications for the Kaska. As Yellowknives Dene scholar Glen Coulthard explains in Red Skin, White Masks: Rejecting the Colonial Politics of Recognition, state recognition of Aboriginal Title runs the risk of reorienting the struggle from one that is informed by the land as a system of accountability and relations, to a struggle for land, understood increasingly in material terms. As such, in 2018 the RRDC took a different approach.

Led by the Elders’ Council and Dena kʼéh gusʼān, the RRDC enacted its own hunting permit system. Rather than expend copious amounts of energy and resources negotiating for rights and title within a settler colonial system or fighting through a settler court, the RRDC took its message straight to the hunters. In 2018 they took out a full-page ad in the Yukon News, announcing that any non-Kaska person wishing to hunt in the RRDC part of Dena Kēyeh/Kaska Country would require a permit issued by the RRDC. Then they got to work. They created a brochure that outlines Kaska Dena hunting ethics, which was handed out alongside permits; they consulted with the Elders’ Council and the community around setting quotas and timelines for permits; and they decided on 11 areas that needed to be off limits to hunting in order to remove pressure in over-harvested places.

The RRDC's 2018 ad in the Yukon News notified hunters that they would need a permit issued by the RRDC.

According to the RRDC’s hunting permit system, the season ends around or before the bulls start rutting, and hunters are encouraged not to take the largest bulls. As former RRDC councillor Derrick Redies told CBC, “We’re really just exercising our inherent right to be self-governing, because we’re not a signed First Nation and we view this as protecting our identity, protecting our culture, and who we are.”

On August 8, 2021, just days after the RRDC and other Kaska neighbours posted their most recent hunting ads, the Yukon government issued a press release addressing hunting in Yukon First Nations Traditional Territories. In the press release, the Yukon government reiterated that “Yukon’s licensed hunters are guided by the Wildlife Act and the rules of general application always apply.” It concluded with this: “Licensed hunters do not require permission to hunt on non-Settlement Lands in any traditional territory.” In other words, the Yukon government applied language and land categories authorized by the UFA to the Kaska hunting context. As noted above, after a land claim agreement has been signed, “non-settlement land” refers to land where Aboriginal Title has been extinguished. In the absence of a land claim, none of Dena Kēyeh/Kaska Country is “non-settlement land.” Yet, here is the Yukon government publicly and inaccurately enforcing a blanket application of the UFA in unceded Kaska territory.

“The land stewards, these are the people that [...] need to be back out there,” he explains. “Their task was taken away by governments. The governments now say, ‘This is how we’re going to do things now.’”

To paraphrase scholar Shiri Pasternak’s book Grounded Authority, in Kaska Country, the struggle is over who has the authority to have authority over the land. The settler colonial state claims this authority even though the Kaska have not signed a historical or modern treaty extinguishing – let alone recognizing or codifying – Kaska rights and title. But settler legal precedent stipulates that Kaska title does not exist until the courts recognize that it exists.

Conversely, the Kaska claim authority over Dena Kēyeh/Kaska Country through their inherent rights. It is the Kaska’s inherited responsibility to land – enacted through Dena k’éh gusʼān and Dena ā́ nézen – that extends them the authority to care for their people, land, and non-human relations. It is the Kaska’s continued presence in Dena Kēyeh/Kaska Country and their staunch refusal of the state’s recognition mechanisms that continue to threaten the Yukon’s settler colonial narratives of domination and reconciliation.

Elder Dorothy Smith recalls what her uncle, Jim Smith, said decades ago: “Never give away the land. Even though many white people are going to come here, don’t let go of our land. What will you eat after that?”

This article was the winner of Briarpatch's 2021 Northern Writing Prize.