Two months into CUPE 3903’s 2018 strike at York University in Toronto, there was no sign of movement from the employer and the picket line spirit was flagging. But in the wake of a series of May Day strike actions, a new idea was born.

On May 7, in the middle of the night, a group of activists returned to their picket line armed with a Rototiller, and under the cover of darkness, they dug up a 525-square-foot plot at the main entrance to campus. Their idea: plant a community strike garden.

“Everybody’s feeling tired and burnt out and exhausted from picket duty,” recalls 3903 member Susannah Mulvale. “We were on this picket line every day, we had this huge space full of grass right in front of us, and we started thinking: what could it be?”

The next day they returned with an array of gardening supplies, “and in 24 hours we had a full garden up and running with flowers, vegetables, all kinds of things,” explains Mulvale.

“We were on this picket line every day, we had this huge space full of grass right in front of us, and we started thinking: what could it be?”

Initially they were worried the employer would tear up the garden, so for the first week shifts of volunteers camped out at the picket line. Once it became clear the employer wasn’t interested in tampering with it, they focused their energy on making the garden thrive. Watering was a challenge. They collected several enormous tubs and found a building near the picket lines with an outdoor water faucet. Each day they drove there, collected gallons of water, and returned to water the garden. When their water source was discovered and cut off after a few months, they resorted to filling the tubs with gallons of water daily from the bathroom of strike headquarters – an even more arduous process.

Laborious as it was, the garden also energized the members involved. “It was nice as a space for people to come together in a healing way, through planting flowers and vegetables there and having this tent set up, this community space,” says Mulvale. “We had ideas of holding events there, having workshops there, making it a space for community organizing and connecting, and just trying to breathe some life into the strike and into each other because we were all so exhausted and burnt out.”

“A lot of members would come and weed, or just visit the garden,” recalls Annelies Cooper, a doctoral student in political science.

For her, the garden was also important in “making sure there is a culture of care and basic needs are being met, and that we are looking out for each other and nurturing each other. I think that is a very necessary tool for a prolonged struggle, whether it’s a strike or something else. At this point we had been on the lines for about three months, and we were tired. The picket line is tiring. It’s hard on your body, and the food can suck, and it’s soul-sucking, and you’re battling against angry drivers every day, and you’re fearing for your life. So I think a lot of us also needed to do the politics of the strike in a way that could also be good for our mental health and our well-being in a broad sense. […] Because you just get so worn down on a picket line.”

How does your garden grow?

“We grew everything!” recalls Mulvale with enthusiasm. “You name it, we had it. All different kinds of lettuce, tomatoes, root vegetables, flowers, herbs, corn, we had everything there. We put mulch down, and we made the anarcho-communist flag – it was half black, half red – so it was a very aesthetic project. There were a lot of creative activities happening around it.”

“We would go back now and then […] and all camp there. We used it as a space to be together, and have some respite from all the politics going on. We did karaoke there once in the middle of the night, at 2 or 3 a.m., sat around a fire. We had dinners there – the first night that we camped out there, people brought up home-cooked food and we had a beautiful feast.”

The garden space precipitated other events as well.

“We had an anti-rainbow-washing Pride action,” recalls Cooper. Rainbow-washing, which refers to corporations and states co-opting the Pride flag for promotional and marketing purposes that do not directly benefit queer people or communities and which sometimes obscure and conceal ongoing oppression, has been the focus of counter-protests during Pride Weeks in recent years. “People gathered at the garden to make the signs and it was a garden-led anti-rainbow-washing of York Pride, which was really awesome.”

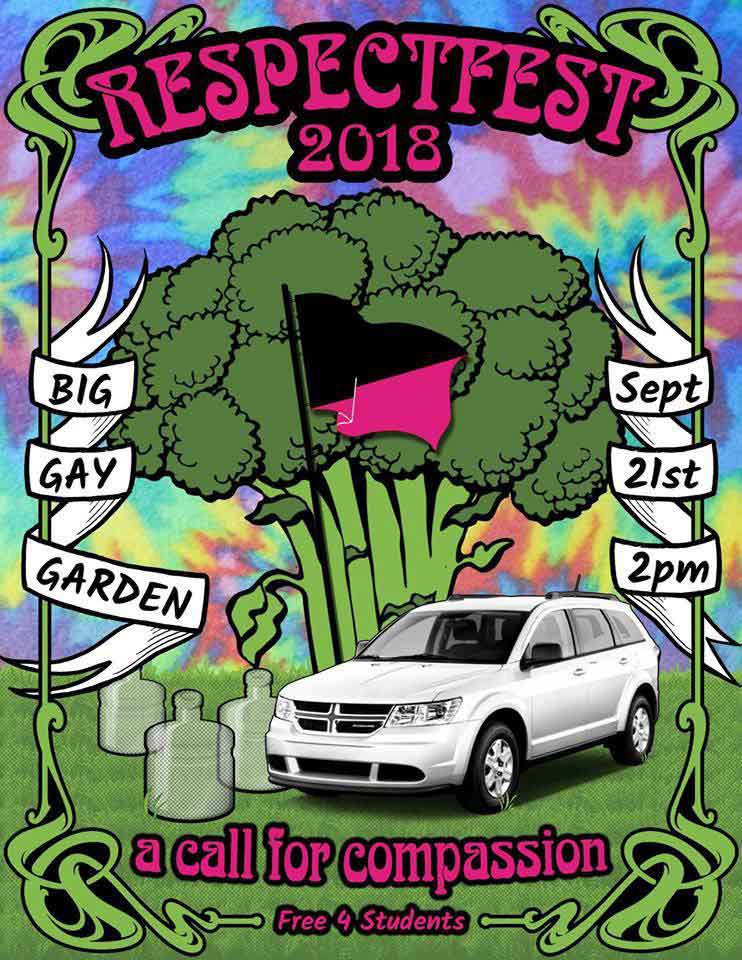

Toward the end of September, the garden played host to a full-day festival. Organizers called it RespectFest as a tongue-in-cheek riposte to the employer’s habit of urging all parties to “behave with respect” while simultaneously launching legal reprisals against activists. One reprisal saw Student Code of Conduct charges filed against five striking graduate students and three undergraduate supporters. The graduate students had union-obtained legal representation to counter the charges (which were tossed out by the Ontario Superior Court), but the non-unionized undergraduate supporters had no access to legal support (the charges came with potential consequences, including fines, suspension, loss of grant funding, and even deportation for international students). RespectFest was billed as a fundraiser to help the undergraduate supporters. It was held in the garden and generated $3,000 for the undergraduates’ legal fees.

When the strike ended on July 25, after the newly elected Progressive Conservative provincial government passed back-to-work legislation, the garden’s fate was uncertain. The university indicated its intention to tear it down, but after a request from organizers, they agreed to let the garden remain until harvest in October.

“That was a nice victory for us because we were quite worried about them just coming in after the strike ended and bulldozing it,” says Mulvale. “We were very attached to this space and there was a lot of energy there, and we didn’t want it to just disappear and for all of our vegetables to be gone. It was a big relief when they said we could keep the garden. We got to end it on our own terms, which was great.”

“Whose university is this? […] It’s not the board of governors’ university, it’s not the president’s university; it’s our university. What do we want to do with it? Well, one idea is to build a garden. For us.”

She says it reflected something members discussed extensively in the lead-up to the strike – how to strike in non-traditional workplaces where picket lines are ineffective. On a sprawling campus like York, with too many entrances to effectively control, the picket lines did little to stop or disrupt most of the employer’s regular operations during the strike. Planting a garden enabled the union to assert space and presence in a different way – to physically transform the landscape of the workplace.

“Picket lines have a historically specific function of shutting down traditional workplaces like factories. So we have to adjust our tactics according to the kinds of workplace we’re in – like what’s actually going to work here? People were easily getting into campus on the subway, we were only holding cars for five or seven minutes, [and] there was still traffic getting in and out of campus.”

Cooper also recalls the garden arising from the question of “what other ways can we actually be locked out of work, but doing something else?”

“A number of classes continued to run, and a number of programs. It felt weird to see things continue as usual. I think having this sort of anarchist guerrilla garden really disrupts that space, and disrupts that business as usual. It really turned the ‘Whose university is it?’ question on its side. […] Whose university is this? It’s ours! It’s students’ and it’s workers’. It’s not the board of governors’ university, it’s not the president’s university; it’s our university. What do we want to do with it? Well, one idea is to build a garden. For us.”

A community effort

CUPE 3903’s community garden was unique in that it emerged during a strike, but they weren’t the first union members to plant seeds, so to speak. UFCW Local 1400 in Saskatoon has operated a community garden since 2015. The local’s Women’s Committee came up with the idea, realizing their headquarters included a lot of land that many of their members, housed in apartment blocks or the city’s downtown, didn’t have access to elsewhere.

Their garden consists of 12 large plots, nine of which are rented out to members. The remaining three are a common garden, and its crops are harvested for the annual Labour Day picnic held by the Saskatoon & District Labour Council. There, the harvest is shared among participants in need. The members who rent individual garden plots share responsibilities for tending the common garden, although social media is used to recruit new volunteers through the growing season.

“We also have shop steward conferences throughout the year, and at those we take people out to the garden,” explains Lucy Figueiredo, secretary-treasurer of the local. “We say feel free – eat some raspberries, come and join us, help us weed. We encourage people to participate in the garden. We get such huge, positive feedback from the membership, just that we have it, and there’s this option available. People are very proud of it.”

“I like it when the union office is more than just walking in and doing a grievance or an arbitration.”

For Figueiredo, the garden makes the union headquarters a more vibrant, interactive space.

“I like it when the union office is more than just walking in and doing a grievance or an arbitration – you’re here for another purpose,” she says. “I like it when members are circulating and doing things here.”

Figueiredo says what really stands out for her is the community and union spirit that emerge during harvesting.

“We’re all in there harvesting and digging stuff up, and you get to see all these members who are not at the union office for a strike vote. That’s what has the biggest impact for me.”

“But the most memorable is always every year, we’re sitting there at the Labour Day picnic, and we’ve got our table of produce that we have to ration out because – it is so powerful – people are lining up to get fresh potatoes, fresh beets, fresh carrots, fresh food that they may not have. It’s so very meaningful that these people are taking it. It shows there’s a purpose for what we did all summer long.”

“Inherently political”

Claire Nettle is a researcher at Flinders University in Adelaide, Australia, and author of the book Community Gardening as Social Action. She notes a long history between unions and gardens. During the enclosure movement of the 1800s in the U.K., the nascent trade union movement played a role fighting for “allotments” for community members. In recent years, gardens have been important to global justice protests. As part of London’s May Day 2000 protests, some of the thousands of protesters in attendance built a guerrilla garden at Parliament Square. In 2011–12, gardens were a common feature of Occupy encampments in the United States, Canada, New Zealand, and elsewhere. In 2012, hundreds of protesters in a suburb of Melbourne established a community garden on the site of a proposed McDonald’s that they didn’t want in their community. For the past decade, “Grow Heathrow” protesters against a proposed Heathrow Airport expansion in London have done the same. But for social movements like organized labour, Nettle says, gardens can play a special role in strengthening membership.

“For social movements, inviting and sustaining people’s involvement, creating community and a shared culture, and developing alternative networks and systems are central tasks in building a long-term, successful movement. Community gardens are a great way of achieving all of these things. Gardening can be a very non-threatening way to engage in positive local action, so an invitation to a garden working-bee might bring out people who are interested in the same issues but might not come to a protest,” Nettle points out.

During the enclosure movement of the 1800s in the U.K., the nascent trade union movement played a role fighting for “allotments” for community members.

“Community gardens can also be a way of communicating a movement’s positive or constructive agenda – what they want to see, rather than what they’re opposed to. People have used community gardens to speak to their visions for an amazing range of issues, from local concerns like access to healthy food, providing community meeting places and protecting green space, right through to global issues like climate change, democracy, and welcoming refugees.”

She cautions that while not all gardens are undertaken for overtly activist reasons, “staking a claim to land to grow food and community is inherently political, and many people have found that the process of starting a community garden – uniting people around a shared project, learning to navigate bureaucratic systems, establishing ways of working together and making a garden grow – can be a gateway to further collective social action.”

Do gardens encourage or neutralize labour movement militancy? Gardens may not appear militant in the way a defiant picket line, protest rally, or blockade – spaces of confrontation characterized by tension and the possibility of violence – might. Yet there is an implicit militancy to gardening, akin to that of squatters who occupy empty buildings to protest unjust allocations of urban housing: it is a transformation of the land in order to benefit the membership or community by growing food. Anti-gentrification gardening initiatives like Grow Heathrow or the Melbourne anti-McDonald’s protest involve proactive, direct-action efforts to transform urban landscapes in the absence of, or in defiance of, authorities.

“Community gardens can also be a way of communicating a movement’s positive or constructive agenda – what they want to see, rather than what they’re opposed to.”

And asserting space is important. Sociologist Jen Schradie, in her recent book The Revolution That Wasn’t, identifies the lack of safe spaces in which to organize as a factor impeding labour organizing in right-to-work states, observing that this is why churches and community centres operated by union allies are so crucial to the health of the labour movement.

Gardening, as a “less radical” activity often conducted in groups, can also help unions and left movements by serving as a sort of “gateway” action designed to increase the activism of members; a confidence- and skill-building precursor to more militant activity. Gardening requires grassroots organizational decision making, allowing rank-and-file members to self-organize and learn to work together in efficient and effective ways. It allows for skill sharing of a sort not otherwise seen in unions, allowing members to draw on knowledge and experience unrelated to the workplace or traditional union-organizing skills, and it might therefore engage and empower a broader cross-section of the membership.

And in the face of strikes that often linger for months with little sign of movement, growing a garden can offer an additional sense of purpose, producing results that are more immediately visible than employer negotiations, which may or may not be happening. As Figueiredo puts it: “It’s really hard to be digging in a garden and pulling out your potatoes and not realize that you are growing something, that you’re just happy, that you’re connected to the earth.”

_780_520_90_s_c1_c_c.jpg)