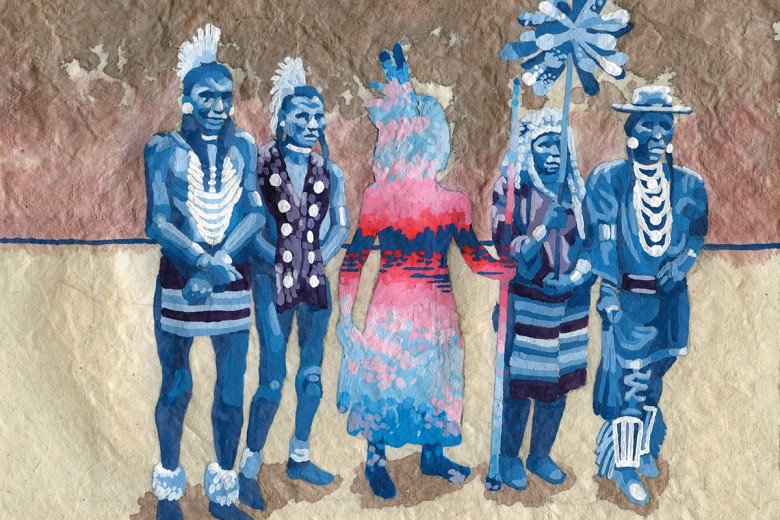

Jane Shi’s recent Briarpatch article, “The revolution will be translated,” offers an empowering account of on-the-ground solidarity between migrant communities in Vancouver and Indigenous peoples during the protests against the RCMP and Coastal GasLink invasion of Wet’suwet’en Yintah (territory). Perhaps most striking is the way in which Shi’s politics are grounded in a commitment to the sovereignty of Indigenous nations. I say this is striking because, according to the activist and scholar Nandita Sharma in her recent book Home Rule, the very idea of Indigenous sovereignty is presumed to be anathema to the well-being of migrant communities. In Home Rule, Sharma denies the relationships of “reciprocal care” that Shi’s article makes so tangibly clear. Sharma’s denial is rooted in misrepresentations of Indigenous nations’ claims to sovereignty, suggesting they mirror those of the Canadian state. Sharma is intent on not seeing what Shi’s article makes so clear: Indigenous governance systems are a cornerstone in (re)building a world in which many worlds can fit, and the crucial role played by alliances rooted in inter-nationalism.

Sharma’s first book, Home Economics (2006), remains a vital resource on migrant justice, particularly for those in the more radical, anti-capitalist and anti-statist parts of the movement. That text provides a materialist account of how citizenship constrains human mobility while enabling maximal profit accumulation by the capitalist classes. She notes how states like Canada facilitate global capitalism by creating populations labelled as “migrants,” whose legal status as non-citizens maximizes the exploitation of their labour. Sharma’s thesis was reaffirmed when Prime Minister Justin Trudeau announced in April that while international post-secondary students are ineligible for COVID-19 relief, the government is lifting its cap on the number of hours these students can work – provided they risk exposure in an essential service.

Sharma’s concern largely comes from her fear that Indigenous sovereignty will maintain or deepen the disenfranchisement of migrants.

Home Rule builds on Sharma’s earlier work, offering an extended historical account of what she calls the “Postcolonial New World Order.” The somewhat conspiratorial tone of a “new world order” aside, in chapters two, three, and five, Sharma offers a generally compelling history of the transition from a world dominated by colonizing empire-states to a “postcolonial” world organized primarily through nation-states. Many present this move from empire into statehood as liberatory, but Home Rule successfully argues that the nation-state system “organized new modes of managing now-national populations and situating each one within globally operative … capitalist social relations” of domination. For example, as detailed throughout Home Rule, despite the state’s promises of equality between citizens, inequality has expanded in nearly all post-colonial states. Sharma suggests that this transition is marked by two important shifts in how states govern: (1) while empire-states typically have no formally declared borders, nation-states define themselves as enclosed, territorial communities; and (2) while empire-states constantly seek to bring more (subjugated) populations into their jurisdiction, nation-states are built by excluding communities from citizenship and expelling populations out of their jurisdiction. This history notes that introducing citizenship controls based on racist exclusions is often among the very first acts of newly self-determining nation-states.

This is significant history for those struggling for migrant justice today, as it evidences that the state system itself creates “migrant” populations and then treats them as a problem. Further, instead of being incidental or aberrational, state violence against migrants is an essential part of the state system. These are key insights that ward off impulses to seek redress for, or inclusion of, migrants within a given state. Sharma compellingly suggests that if migrant justice is to be meaningful, it must consider the deepest anti-statist claims put forward by those demanding a world of “no borders” and in which “no one is illegal.”

In spite of these strengths, the depths of Home Rule’s flaws make it a text with little to offer for anti-colonial work. Particularly jarring is the misleading way Sharma treats the anti-colonial struggles of Indigenous peoples against settler colonies such as Canada. Sharma wrongly asserts that Indigenous nations’ claims to sovereignty are rooted in a political ideology that not only mirrors the exclusionary logics of nation-states, but that they also share theories of ethno-national purity with white supremacist groups. This treatment of Indigenous nations’ sovereignty resembles the tremulous claims that racial justice struggles endure from reactionaries alleging “reverse racism.” Instead of white fragility, in Home Rule we find abundant settler fragility.

This treatment of Indigenous nations’ sovereignty resembles the tremulous claims that racial justice struggles endure from reactionaries alleging “reverse racism.”

What is perhaps most frustrating is that Sharma merely asserts that Indigenous sovereignty reflects Eurocentric theories of sovereignty; Home Rule offers no sustained engagement with the history of inter-nationalism in many Indigenous communities – such as that which Robert Innes details in Elder Brother and the Law of the People. Nor does Sharma engage with non-exclusive and non-exclusionary Indigenous theories of sovereignty, as exemplified by the governance systems of the Dish with One Spoon treaty in Leanne Simpson’s 2008 article, “Looking After Gdoo-naaganinaa.” It is only through a lack of Indigenous voices that Home Rule crafts its caricatures of Indigenous sovereignty.

Sharma’s concern largely comes from her fear that Indigenous sovereignty will maintain or deepen the disenfranchisement of migrants. She believes that Indigenous anti-colonial struggles root themselves in understandings of belonging solely through membership within the nation and that it “conflates migration with colonialism.” Importantly, Sharma is not saying – as do many on the political right – that all colonization is merely migration. She recognizes that Indigenous peoples face a history of colonization, though she denies the contemporary relevance of this by constantly referring to Canada as a “former White Settler Colony.” By downplaying Canada’s ongoing colonization of Indigenous nations, Sharma not only recreates racist and colonial ways of thinking that deny the political authority of Indigenous peoples, she also avoids confronting the fact that the mobility rights and material well-being of all settlers are presently structured by a state that maintains itself through the suppression of Indigenous sovereignties. This remains true even as it is also imperative to acknowledge that settlers’ access to the full privileges stolen through colonization differs enormously based on hierarchies of citizenship, race, class, ability, gender, and so on.

The stakes of Sharma’s thinking are significant. Her misrepresentation of Indigenous sovereignties threatens to drive a wedge between Indigenous nations and migrant communities — arguably two groups most deeply affected by white supremacy and colonization, and who therefore have potentially the most to gain through solidarity. Further, in her well-placed effort to suggest that colonization is about more than just the theft and domination of one nation’s land by another, Sharma overextends her argument by implying that this type of domination is not experienced by particular people/nations in particular places and times but is rather a generalized ahistorical condition of most of humanity. By rejecting the resurgence of Indigenous sovereignties as a cornerstone of decolonization, Sharma ignores the ways in which her call to “regain a world held in common” merely reproduces the colonial denial of Indigenous nations’ sovereignty.

Her misrepresentation of Indigenous sovereignties threatens to drive a wedge between Indigenous nations and migrant communities — arguably two groups most deeply affected by white supremacy and colonization, and who therefore have potentially the most to gain through solidarity.

It may be helpful to conclude by considering the vignette with which Sharma opens the book, as it reveals how she thinks about the foundations of solidarity. Home Rule begins by recounting the biblical Tower of Babel story. In Sharma’s retelling, the Tower, built following the Flood, symbolizes a “regenerated” humanity setting itself “on the path of a great collective endeavour” of “common purpose and a shared vision.” Sharma suggests that God, jealous or fearful, cursed humanity with distinct languages, thereby “separating people one from the other” and terminating the basis of their solidarity. Sharma’s idea that a shared language is necessary for collective action is not only troubling given Canada’s more than 150-year effort to destroy Indigenous languages, it also fails to recognize the vital bridge-work of translation carried out by people like Jane Shi.

In this retelling, we can also see Sharma’s disturbing presumption that solidarity emerges from that which is common or shared; for her, difference must be overcome to create space for solidarity. There are, however, other post-Flood stories that Sharma could have turned to for richer theories of solidarity: I think of Robin Wall Kimmerer recounting in Braiding Sweetgrass that, in the Potawatomi creation story, Turtle Island itself was constructed through Skywoman embracing her relatives’ differences, rather than in spite of them. If Sharma had seriously grappled with the Toni Morrison quotation she uses as an epilogue, she may have seen that her own call for a commons devoid of Indigenous sovereignty is itself an idea of “[p]aradise [that is] premature, a little hasty if no one could take the time to understand other languages, other views, other narratives.”

Read Nandita Sharma's response to this review here.