“I come from the dreams of my ancestors.”

—An affirmation for queer people of colour

-

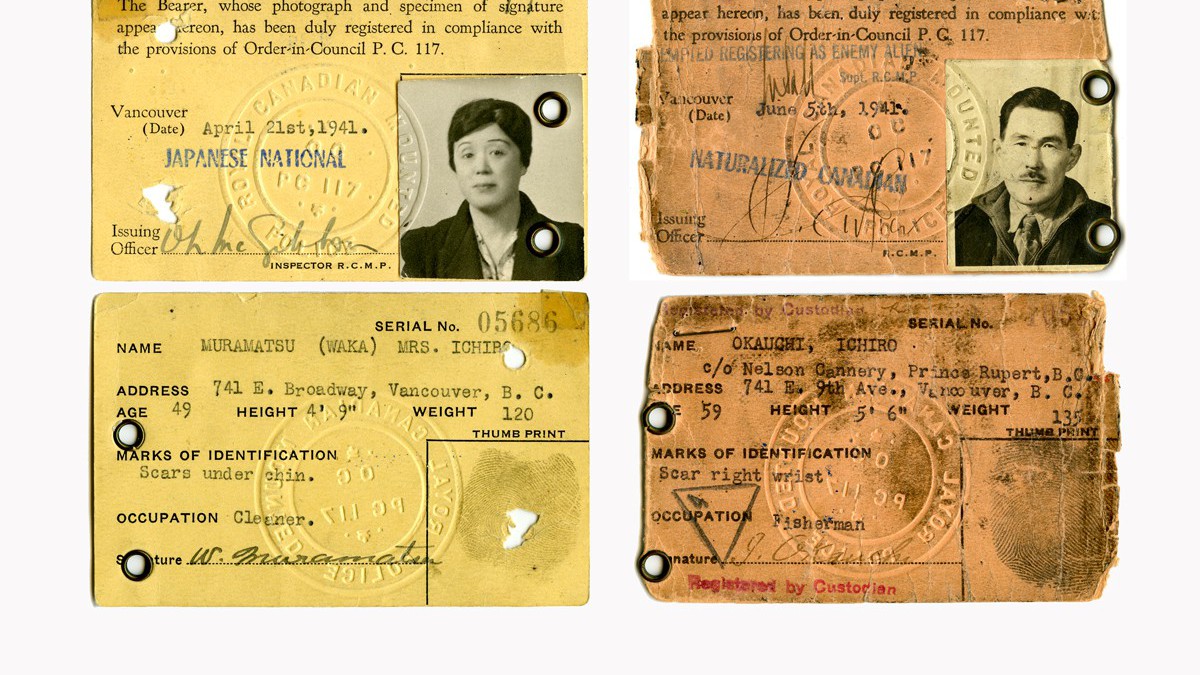

In the palm of my hand, I delicately finger a pair of unfamiliar ID cards printed on worn pieces of coloured paper, yellow and salmon pink. The faded type reveals they were issued in the spring of 1941 with approval from the Royal Canadian Mounted Police. The yellow marks my great-grandmother as a Japanese National and the pink indicates my great-grandfather was a naturalized Canadian. Between my thumb and index finger, I clasp these rare and coveted discoveries: names, addresses, heights, weights, occupations, and even marks of identification on their bodies. I practise saying my ancestors’ names aloud, slowly, so I do not forget, but I have never learned to speak Japanese and am self-conscious about my pronunciation. I realize there is a third colour of these cards – white – that I am missing. White was only assigned to those who were born in Canada.

-

Today, I will start building a sculpture out of hundreds of replicated registration cards from the Second World War. The sculpture will represent over 8,000 Japanese-Canadian people, including my oba-chan and her family, who were taken from their homes in coastal B.C. and detained in the stables and exhibition buildings at Hastings Park in East Vancouver. I grew up eating mini-doughnuts at the PNE Fair in Hastings Park during my childhood summers, but nobody in my family spoke about this history. I don’t know if they even knew.

-

I have made copies of the real ones my oba-chan left behind after she died. These registration cards identified her parents, my great-grandparents, who were 49 and 59 years old, respectively, when the war broke out. I found the cards in an old box of her things in a closet at my parents’ house: tucked in her fake snakeskin wallet, among my grandpa’s funeral papers and an album filled halfway with fading Fujifilm photos from the ’80s. Photos taken when my grandparents returned to British Columbia, after they fled Montreal in the ’70s. They’d lived in Montreal after the war had ended, when they were not allowed to return to the West Coast.

-

In 1942, my family was given 24 hours’ notice to pack suitcases and leave their homes. Perceived as an ethnic threat by the government of Canada, they were displaced from the “security zone,” a 100-mile zone along the West Coast, to isolated internment camps or towns such as Tashme, New Denver, and Greenwood. Tourists now find these remote small towns charming and lovely. It’s just a different pace of life, you know? I hear the skiing is great in the Kootenays. The snow-capped mountains epitomize Canadian winter. In photos, the fog descends like a veil, nearly masking the violence. It must have been cold to live there in a tarpaper shack.

-

The U.S. government instituted a Muslim registry in September of 2002. Even though it was suspended in 2011, President Trump tweeted about bringing it back. His supporters are keen to use Japanese-American internment camps as a “precedent” for immigrant registry.

-

Canadians talk shit about Americans as if we have no blood on our hands, as if we don’t shop on Amazon, as if we didn’t massacre Indigenous people, as if we don’t have an epidemic of type 2 diabetes, as if we didn’t elect Doug Ford, as if we didn’t jail over 80,000 migrants (including children) without charge between 2006 and 2014.

-

Did you know that migrants in Canada can be detained without any criminal offence? Each time I visit the public library in downtown Vancouver, I climb the escalator, rising higher and higher beside where migrant holding cells are hidden, in the adjoining building, shrouded from public awareness. Such secrets are often concealed in plain sight – places where we do not ask questions.

-

In university, I learn that climate change is increasingly forcing migrants to flee their homelands and cross borders into other countries. In the Philippines, Typhoon Haiyan was one of the strongest tropical cyclones ever recorded. In Bangladesh, rising sea levels are displacing coastal people from their homes. I eventually realize that we won’t really talk about this much throughout my social sciences degree. Our professors will acknowledge that, on a global scale, Western countries are disproportionately to blame for climate change, but mostly, we learn about ways to make change as individuals. We try and lead “sustainable” lifestyles. We learn how to meditate. We convince one another to eat less meat. We ride our bikes. We compost. We plant community gardens. We are against climate change. We are united. We turn off the lights, save energy, and do not see race.

-

I am often only one of two or three people of colour in my environmental studies classes. Sometimes I am the only one.

On the first day of an intensive field course on Indigenous land management practices, a white woman professor leads an “icebreaker” activity. The class follows her instructions as she asks us to stand in groups representing an ancestry or culture we come from.

Four or five large groups form around the classroom: Dutch, Irish, British, French, Scottish.

I stand alone.

She instructs us to circulate among other groups and convince their members to “join” ours. We would do this by using “fun stereotypes” about our culture as a persuasion tactic. The example she offers us is something like, “come be British with me. We drink lots of beer!” The professor smiles at all of us, her face beaming, as students circulate and begin to break the ice.

I think about stereotypes. I think about the “stinky” lunches I brought from home to school, the ching chong noises, how I was never all that good at math. The stereotypes I have had flung at me are not quite as fun as I imagine it might be if you’re white and British and have far less internalized racism. I leave the classroom, my face flushed, cheeks damp, chest tight. A red-headed classmate follows me, knocks on the door of the bathroom stall. She invites me to join her and the others in the Dutch group. I decline. Playing a game of assimilation – even if only for pretend – just doesn’t seem all that fun.

My professor later tells me this was not her intention. This was not her intention at all. She learned this game from sensitivity training in diversity and inclusion.

-

I wake up one day to breaking news on the CBC: Hurricane Maria has devastated Puerto Rico. So far at least 15 people are dead. The electricity is out. President Trump is planning a visit.

-

“I repeat, Hurricane Maria has hit Puerto Rico. The hurricane has made its way to the Caribbean. President Trump still has not made an appearance.”

-

President Trump tweets about how hard hit Puerto Rico is. How much debt they still “owe” the United States of America. He makes no mention of America’s occupation and theft of Taíno lands since 1898.

-

A week after the hurricane, I lie in bed, tossing and turning, sheets cast aside. It’s too warm a night for blankets. In my grogginess, my limbs sprawl out, lying in a starfish float position atop the mattress. From the edge of my pillow, I cautiously peer toward A, my partner, who is lightly snoring and fast asleep. We’d basically just u-hauled after a flamingly gay summer romance, and sleeping as bedmates is still a new-ish feeling to which my body is getting accustomed. By the time the clock ticks to 3:30 a.m., I am too tired to fight my eyelids any longer. I finally fall asleep and dream.

I dream A and I are at a body movement workshop. The studio space is in the top corner of the building, in a room with big windows through which we can see out to a lake. It feels familiar somehow. It reminds me of the community arts centre where I attended dance classes as a kid – classes where we spent most of the time running around the room and waving colourful scarves. In my dream, we are sitting on the floor in a circle with the other participants. A brown woman with long dark hair pulled into a ponytail begins talking about climate change and the impacts on Indigenous and people of colour around the world. I begin to cry in the circle. This woman and I make eye contact. She acknowledges me.

I wake up in my bed beside A. I feel safe again. Less anxious than before, somehow.

-

Nobody talked about our family history while I was growing up, so I’ve been working toward uncovering it on my own. Sometimes I get so immersed that I forget how heavy-hearted it all is. When I am able to pause and pull away, see it through someone else’s eyes, or relate it to the present day, my heart gets whomped.

I wonder, how can I feel such heartache while simultaneously falling in love for the first time?

-

These days, my other main squeeze is writing. When I first started sharing my work, I submitted a piece to the environmental studies student newspaper at my school. The article explored food deserts and inequities in access to healthy and culturally appropriate foods in the American south, where people are divided by both race and class.

My article was printed on the last page of the newspaper, beneath two pieces on animal rights. Most of the other articles were about individual change. About how we can lead more sustainable lifestyles. Learn how to meditate. Why we should eat less meat, ride our bikes, compost, or plant more community gardens. Why we need to stand against climate change. Why we need to be united. Why we need to turn off the lights to save power. There was nothing else about race.

-

I can’t recall when I stopped calling myself an environmentalist.

-

I listen to podcasts now. I listen to people talk about issues that impact their daily lives, straight from the source. One episode I heard recently discussed climate impacts on poor brown migrants in the U.S. The kind of stuff no one seemed to want to talk about in class.

“…the Angelenos who are disproportionately feeling that intense heat, they live in urban areas with substandard housing, fewer trees. They’re surrounded by freeways […] majority Black and brown. […] Mother Nature may not discriminate, but people do.”

I listen differently now.

-

While I construct this sculpture of registration cards to mark the 75th anniversary of Japanese-Canadian internment, it often feels like the world is still asleep. I don’t want to think I’m a self-serving, apathetic millennial, but I can’t seem to follow the news anymore without crying. Is it terrible to admit I would rather watch Ariana Grande’s Instagram stories than the 6 o’clock news? I don’t even have cable TV in the first place.

When I wake up, will the climate justice movement finally be led by front-line Indigenous women, peasant farmers, or migrant workers?

-

On grey days, flowers still bloom.

The news reports the sakura trees in Japan are blooming months early this year. On account of the typhoons and the extreme weather and all that. The cherry blossoms don’t know any better.

I think they’re just trying to survive.

This article was the winner of the creative non-fiction category of our eighth annual Writing in the Margins contest. Creative non-fiction entries were judged by Alicia Elliott. We gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the Regina Public Interest Research Group (RPIRG) to this year’s contest. Briarpatch will be accepting entries for the ninth Writing in the Margins contest in September 2019.