At 6 a.m. on Tuesday, March 20, Lucy Francineth Granados had just finished folding her laundry and was about to leave for work when she was caught off guard by a loud knocking at the door. Before she knew it, she was surrounded by four Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA) officers who brutally forced her to the ground, injuring her arm in the process. Lucy was brought to the Laval Detention Centre, and is now due to be deported to Guatemala on March 27th.

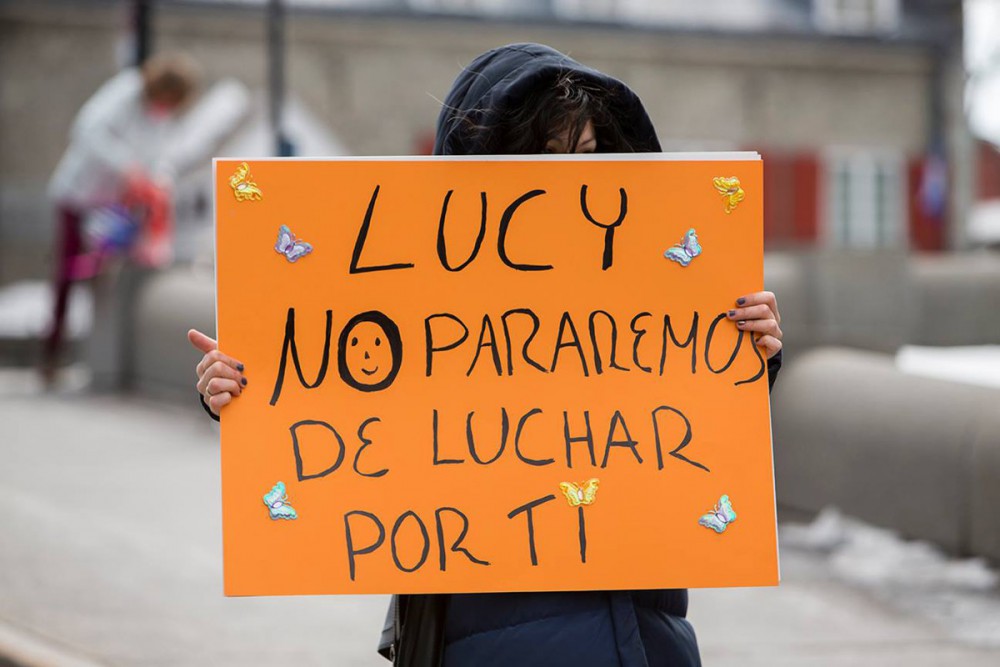

Lucy is one of the over 500,000 people living without status in Canada. A core member of the Non-Status Women’s Collective and the Temporary Agency Worker Association, she has become a fixture in her Montreal community over the last nine years, as an outspoken migrant justice advocate and a source of support for other non-status people. She is the sole source of financial support for her mother and her three children, who live in Guatemala and depend entirely on the remittances that Lucy sends for food, housing, and school fees.

Like many others, Lucy arrived in Canada seeking stability and economic security for herself and her family. After her refugee claim was refused, and all other legal channels for permanent status had been exhausted, she made the difficult decision to remain in Canada, living under constant threat of deportation.

For a non-status resident like Lucy, there is only one available avenue to regularization: a humanitarian and compassionate grounds application. Humanitarian and compassionate grounds can apply in “exceptional cases,” and the decision is made on a case-by-case basis. But the application is costly – Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) administrative costs for a H&C application are $550 per adult, not including legal fees, which average around $2,000 per application. And even if a non-status person can get together the money, the process of applying can put them at risk of arrest.

Decisions on humanitarian and compassionate grounds applications are left in the hands of a single immigration officer who studies the file to determine whether the candidate meets Immigration Canada’s assessment criteria. To have a strong application, an applicant must typically provide extensive documentation about their personal life, including their address, work, family, friends, networks, and community in Canada. The immigration officer has the discretion to share the applicant’s information with the CBSA, which they often do; border agents routinely show up at applicants’ homes within days of their H&C applications being received by IRCC.

Lucy hoped that submitting a H&C application would allow her to finally be able to attain the security she had been seeking after so many years of living in precarity, working piecemeal childcare and cleaning jobs for placement agencies at less than minimum wage. She spent months gathering the necessary money and paperwork, and finally submitted the application with the help of a lawyer in September 2017.

In January of this year, however, a CBSA officer informed her lawyer that Lucy’s file would not be studied unless she turned herself in to face deportation. Under Canadian immigration law, this is illegal: section 25 of the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act states that the Minister must study all humanitarian applications filed inside Canada – barring some exceptions that don’t apply to Lucy. The actions of this agent have nonetheless been carried out with impunity: neither Immigration Canada nor the CBSA have responded to Lucy’s lawyer’s request to clarify the situation, despite calls from activists to investigate the CBSA officer and bring charges if warranted.

On the surface, Lucy’s case looks like it might exemplify the misconduct of a rogue officer – but it also highlights the dangerous arbitrariness of the case-by-case system. In order to protect themselves against future deportation, applicants must first deliberately put themselves at risk of deportation – the system itself is almost sadistic in its demand for vulnerability. An applicant’s freedom and status rest in the hands of one agent, who can make it impossible for someone to access the single legal channel available to regularize their status in Canada.

Rather than achieving the stability that she had hoped for, her H&C application led to Lucy’s worst nightmare: being violently apprehended and detained by the CBSA, only to face imminent deportation.

There is very little that is “humanitarian” or “compassionate” about the current case-by-case system. It is unacceptable that the only path to possible regularization puts those with precarious status at mercy of the authority of the Canada Border Services Agency – an agency with no oversight body and a history of clear acts of abuse.

The very least the Canadian government can do is ensure that Lucy’s application is processed and that she receives a full decision before being uprooted from the community that she has spent so many years building. Her violent arrest only reinforces the message that non-status members of our community must remain in the shadows, isolated and in fear.

But Lucy’s story also reminds us that processing an application before deporting someone is not enough. We must continue to fight against the injustices of the immigration system, to move beyond a case-by-case structure and implement a comprehensive regularization program that guarantees the safety and dignity of all non-status people who live here.

Information on how to help stop Lucy’s deportation by emailing or calling public representatives can be found here, on the Solidarity Across Borders website.