Over the past decade, workplace anti-gossip policies have proliferated under the guise of protecting workers from bullying and rumours. Many employers include boilerplate anti-gossip policies like this one in employee handbooks: “Gossip is not tolerated in the workplace. Gossip is any conversation about another person in which the other person is not present, or in which the participants have no power to change the situation.”

When I first encountered an anti-gossip policy as an employee, I was grateful. I’d seen how gossip can make workplaces hostile. In one coffee shop I worked in, the rumours were constant: who was or wasn’t getting promoted and why, who was pregnant, who was getting divorced. It made me and my co-workers anxious – anyone could be talking about you behind your back.

But at my new workplace, I quickly learned that the anti-gossip policy was there to protect management, not workers. Under its terms, discussing wages or problems in the workplace could be considered a violation of policy. For staff who had complaints about racism, homophobia, sexism, and bullying, discussing these concerns was verboten. When a co-worker and I messaged about dealing with a frustrating client on a work chat, management scheduled a disciplinary meeting to let us know we’d broken the anti-gossip rule just by commiserating.

Worse, when a co-worker spoke up about racism in the workplace and asked a fellow employee for help with the issue, she was silenced and subjected to disciplinary meetings. The anti-gossip policy was used to avoid dealing with the underlying issues she’d identified.

But at my new workplace, I quickly learned that the anti-gossip policy was there to protect management, not workers. Under its terms, discussing wages or problems in the workplace could be considered a violation of policy.

This environment made union organizing nearly impossible. Workers feared talking to each other, concerned that any discussions they had might be construed as gossip. Much of what management considers workplace gossip is about the work itself: identifying problems, venting about customers, or calling out racism – exactly the problems that make people want to organize in the first place.

Trying to understand the impacts of these policies, I began to research their effect on worker organizing.

In the United States in 2013, the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) struck down an anti-gossip policy at Laurus Technical Institute near Atlanta; the policy prohibited “making negative or disparaging comments or criticisms about anyone; creating, and sharing or repeating, a rumor about another person; and discussing work issues or terms and conditions of employment with other employees.” The policy had been used to fire an employee for discussing a complaint she had filed alleging sexual harassment and retaliation by her manager. The NLRB judge ruled that the policy was unlawful, on the basis that it was too broad and violated workers’ rights to discuss wages, working conditions, and unions.

In Canada, workers have many of the same legal rights to talk about unionization and participate in union activities at their workplaces (if not necessarily during working hours). However, much like the policies forbidding workers from discussing salaries, anti-gossip policies can be used to circumvent the laws that exist to protect workers’ interests.

“If we’re talking about organizing and solidarity, it is so important for workers to be able to talk to other workers about how to be safe, happy, healthy, and productive, and to feel integrity and dignity at work,” says Bradley Lafortune, a former labour organizer with the Alberta Federation of Labour and executive director of Public Interest Alberta.

“In my opinion, it’s an overstep to allow for a black-and-white anti-gossip policy […] that doesn’t allow for people to talk to each other about their workplace conditions. That seems like a massive overreach,” says Lafortune, who has seen first-hand how workplace gossip can lead to material changes in the workplace, like confronting pay inequity.

“You have to be able to talk to Carol at your workplace, just listen to her about her kids for five minutes, and then say, ‘Carol, don’t you hate working through your breaks?’”

Taylor, a worker at an Alberta non-profit who asked to use a pseudonym, tells me that the anti-gossip policy at her workplace seemed innocuous – until it didn’t. “I don’t think [the policy] raised any red flags until it was clear that things that should have been okay, like talking to your colleagues, was frowned upon,” she says. The policy at Taylor’s workplace defined gossip as “any conversation about another person in which there is no first-hand knowledge.”

Leanne, a unionized lab worker from Alberta who also asked to use a pseudonym, uses gossip in her workplace to understand her co-workers’ concerns and to channel their frustration into action.

When her manager instituted a vacation policy that violated their contract, Leanne circulated a petition against it. Her co-workers signed the petition, and the policy was reversed. Gossip, she says, was key to understanding her co-workers’ concerns, and harnessing their collective power. Approaching her co-workers in the parking lot after a shift, or in the break room at lunch, Leanne asked simple questions to understand their issues better: how is work going for you? What is frustrating you?

“You have to be able to talk to Carol at your workplace, just listen to her about her kids for five minutes, and then say, ‘Carol, don’t you hate working through your breaks?’” says Leanne.

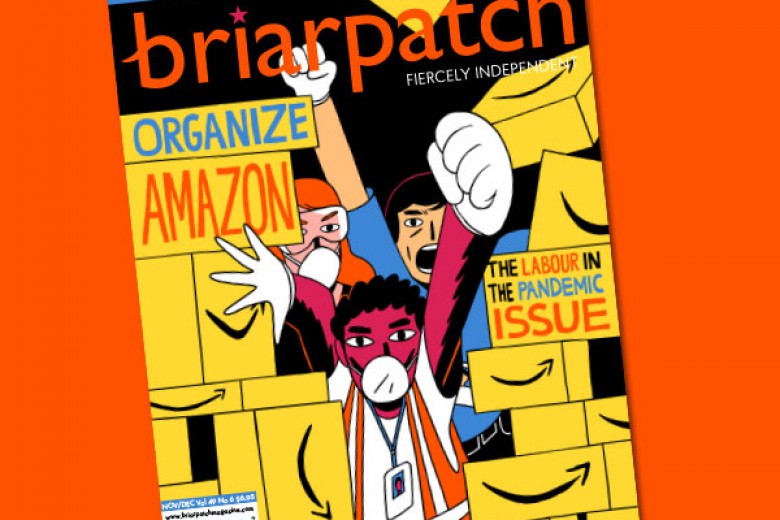

Since COVID restrictions have made it harder for workers to see their co-workers outside of work-sanctioned Zoom meetings, anti-gossip policies hold even more power. During the pandemic, workers have experienced heightened surveillance, especially those working from home: software like Staffcop, Hubstaff, and Time Doctor are used to track keystrokes, log GPS coordinates, take screenshots of employees’ computers, and provide managers with breakdowns of how much time workers spend typing or moving their mouse. Companies such as Amazon and Walmart monitor employee conversations on Reddit, Facebook, and listservs to keep tabs on union talk and to shut it down.

Banning any negative conversation in the workplace, rather than preventing hard feelings, represses them.

“They can quantify the time you’re spending with someone and identify that as a threat,” says Taylor, who avoided official channels whenever she interacted one-on-one with colleagues. Once she was labelled an agitator by management, she felt watched and nervous to talk to her colleagues.

“One of my other co-workers is having that issue – she was organizing her workplace and then the pandemic happened and it got cut short because everyone had to work from home,” Leanne commiserates.

Gossip is typically seen as the cause of workplace issues, when it should be seen as a symptom of a deeper problem. Banning any negative conversation in the workplace, rather than preventing hard feelings, represses them.

The conversations that workers have on smoke breaks or at the pub orient them to the job site. Through gossip, workers learn how to survive in their workplace. They learn who always knows where things are in the freezer or how to fix the copier; they develop whisper networks to protect fellow workers from harassment.

Psychologist Jennifer Newman told CBC that gossip can be good for workers “[t]o figure out expectations and identify short cuts to getting things done.” Research from Stanford University supports the idea that gossip is a useful tool in social groups of all kinds. Their study of gossip and ostracism showed that gossip helped participants find co-operative people and ostracize selfish ones.

“I for sure see it as a good thing,” says Taylor, whose co-workers oriented her to her new workplace through gossip. “It’s like, ‘Oh, you won’t click with this person.’ You can say it in a subtle way. But it’s like, avoid that person at all costs.”

Gossip can be survival, especially for women, people of colour, and other workers who don’t have the same connections as the people at the top.

“Gossip is integral. It shows you how your workplace is organized,” says Leanne. “Go and talk to your co-workers. That’s really the first step to organizing.”

Although the goal is to build a positive environment, anti-gossip policies instead create a culture of fear. In my workplace, employees avoided expressing any negative emotions for fear of disciplinary action. The only safe place to organize was at my apartment. Two co-workers I had become close to were over for dinner when we started discussing the need for a union. Back in the office, management reassigned our desks so we no longer sat together. Our daily gossip could no longer take place inconspicuously. Spread across the office, we could no longer quietly compare pay stubs and whisper the word “union.”

“Go and talk to your co-workers. That’s really the first step to organizing.”

By the time we got the ball rolling with a union organizer, the pandemic was in full swing and we were mostly working from home. All communication, from virtual happy hour to work emails, was monitored more closely. Fear of retaliation was high. Staff were afraid to sign a union card or to be found out as a member of the private WhatsApp group through which we organized.

We failed to rally my co-workers and get union cards signed. Many other staff and I either left or were fired. The environment created by the no-gossip policy left people feeling atomized and powerless. The culture of racism and silence meant people quit rather than sticking around to try to fix a workplace that ultimately felt too broken.

Anti-gossip policies, like other ostensibly good policies, are wielded by management to keep workers from building solidarity and transforming their workplaces.

Lafortune says, “I’m hopeful that workers will continue to have conversations and gossip as much as they want about making workplace conditions better.”