One day earlier this year, the phone rang in the Briarpatch offices. The woman on the end of the line told me she lives in a small town in northern Saskatchewan, and she had a story she wanted Briarpatch to investigate. “Someone is cutting down the trees,” she said. “All around town, they’re cutting down trees, and no one will say why.”

I explained that Briarpatch is a national magazine, and one with extremely limited capacity – we simply don’t have the money to send a reporter out to northern Saskatchewan.

“This sounds like a story that would be better suited to your local paper – maybe you could contact a journalist in town,” I suggested.

“We don’t have a local paper,” she replied.

Reader, if you don’t already, imagine living in a community where there’s no journalist in town; things are happening and there’s no one dedicated to figuring out why. That’s increasingly the case for many communities in Canada. Between 2008 and 2018, over 250 Canadian news outlets have been shuttered, and at least 189 of them were community papers.

In her cover article, “There’s no journalism on a dead planet,” Sophia Reuss argues that a healthy media landscape is one of the most important tools we have in the fight to save our planet – and ourselves – from climate disaster.

The climate crisis is the biggest story of our time, but it’s a story that’s extremely difficult to tell. The philosopher Timothy Morton calls climate change a “hyperobject”: it’s “massively distributed in time and space such that any particular (local) manifestation never reveals [its] totality.” Put more simply, climate change itself is hard to see and hard to feel.

But those national and global stories alone won’t convince readers that, when it comes to climate change, they have skin in the game or the power to change the course of our society and planet.

Small local stories are part of bigger patterns – for example, a story about cutting down trees in northern Saskatchewan is also a story about the ongoing violation of treaty rights across the country; Canada’s corporate-dominated and export-oriented forestry industry; fascist Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro’s arson of the Amazon; and the worldwide loss of carbon sinks and biodiversity. But those national and global stories alone won’t convince readers that, when it comes to climate change, they have skin in the game or the power to change the course of our society and planet. Journalists need to put it in terms that people understand, using stories that make it hit close to home.

But I should place blame where it’s deserved. As Reuss makes clear in her article, understanding the decline of Canada’s local news means looking at who owns it.

It should come as no surprise that Postmedia – the country’s largest newspaper chain, which is 98 per cent owned by U.S. hedge funds – was the owner responsible for shuttering the most local news outlets between 2008 and 2018. In 2013, as Reuss explains, Postmedia signed an agreement with a lobby group, the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers, to “amplify our energy mandate” and “leverage all means editorially, technically and creatively to further this critical conversation.” As a result of that agreement, Postmedia papers ran paid advertisements for the oil industry, written and presented in the style of editorial content – at least two of which weren’t even marked as ads. And I should add that until 2018 the Province, a daily newspaper owned by Postmedia, had a formal partnership with a company working to promote a liquefied natural gas (LNG) refinery in the community of Squamish, B.C.

As a result of that agreement, Postmedia papers ran paid advertisements for the oil industry, written and presented in the style of editorial content – at least two of which weren’t even marked as ads.

Corporate media owners aren’t interested in helping communities secure a livable future – they’re interested in improving their own bottom line. And they’ll shutter local papers and cozy up to oil industry lobby groups in order to do so.

As we struggle to confront climate change, unless we shift power out of the hands of the wealthy – and that includes power to own media and control its narratives – we’ll end up with new versions of the same stories. These are stories that see poverty as inevitable, that see Black and brown people as collateral damage, that see ever-increasing consumption as natural and desirable. We’ll end up with “solutions” to environmental destruction that fail to change the underlying issues of colonialism and capitalism.

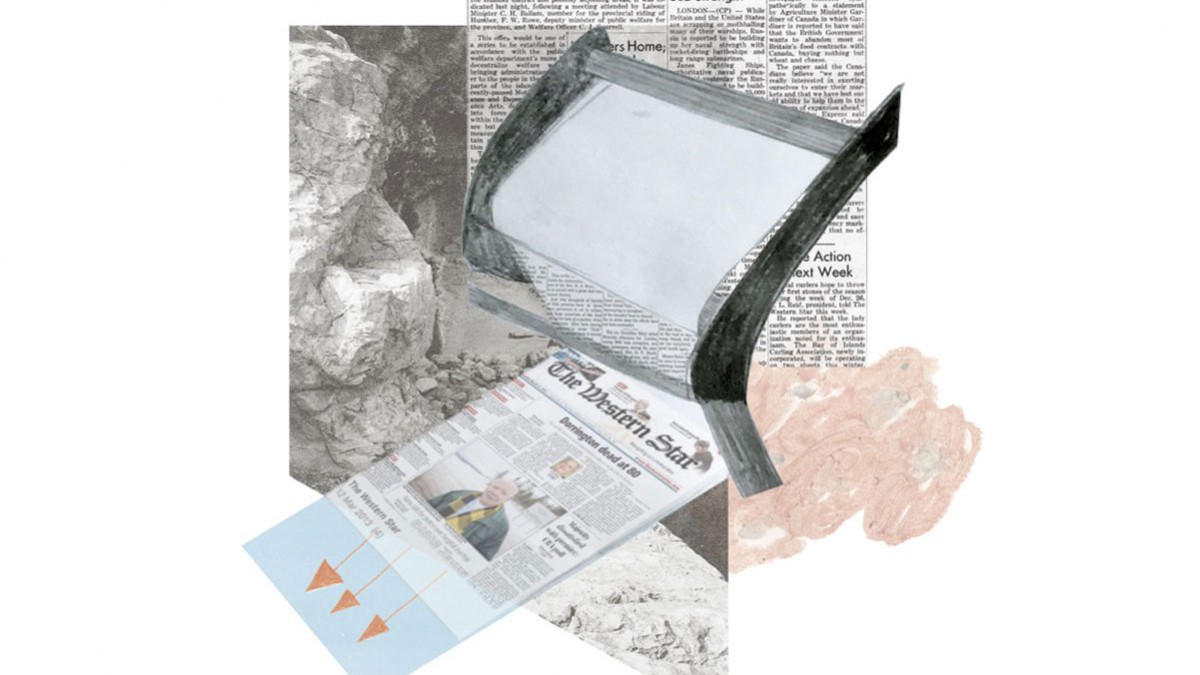

We need sweeping regulatory changes to Canada’s media landscape to prevent the kind of corporate consolidation and impunity that we are now contending with. But at the same time, we need to create and fund our own alternatives to corporate media. Reuss’ cover story is full of examples of people taking media into their own hands – like the activists who created The 4 O’Clock Whistle, a zine born out of the Occupy movement of 2011, which was instrumental in changing the debate around fracking and mining exploration in the city of Corner Brook.

Independent local media – media which encourages people to be attentive and involved in their community, which treats ordinary people as experts on their own lives, which empowers them to demand respect and dignity, and which centres the marginalized – will be an essential part of a truly just transition.