Rosalyn Roy was driving home from the Gulf News office, where she used to work as a local reporter, when she noticed a young girl alone and holding a handwritten protest sign, perched on the wall in front of the Channel-Port aux Basques town hall.

Roy immediately drove home to get her dog – “I find having a dog in a small town is an easy icebreaker; he’s three years old and looks like a puppy” – before heading back to the town hall. The lone protester turned out to be 14-year-old Emma Osmond, the only student in Channel-Port aux Basques, Newfoundland and Labrador, to participate in Canada’s countrywide student climate strike on May 3. (Thousands of Canadian kids walked out of schools across the country with Emma, and the global student strike on May 24 drew an estimated 1.4 million people across 118 countries.)

“She was shy at first,” Roy recalls, “but once we got into talking about something that clearly mattered to her, she opened up and shared.”

The next day, Roy – who was born in Channel-Port aux Basques and whose mother was named after the founder of the Gulf News – submitted her article about Emma and the climate strike for publication.

When it comes to reporting on these climate issues, Roy believes her style of hyperlocal reporting is imperative: “You need to be boots on the ground.”

Emma may have been the only climate striker on May 3, but Channel-Port aux Basques, like many Maritime communities, has undoubtedly begun to feel the impact of the climate crisis. And when it comes to reporting on these climate issues, Roy believes her style of hyperlocal reporting is imperative: “You need to be boots on the ground.”

“Climate change is a particularly important issue in Newfoundland and Labrador because of our geography, social layout, and population distribution,” says Conor Curtis, an activist, writer, and resident of Corner Brook, a city on the west coast of Newfoundland. “And it deserves more attention than it gets.”

But the climate issues that Roy says dominate national news – she cites stories about flooding in Ontario and Quebec – don’t resonate with her community.

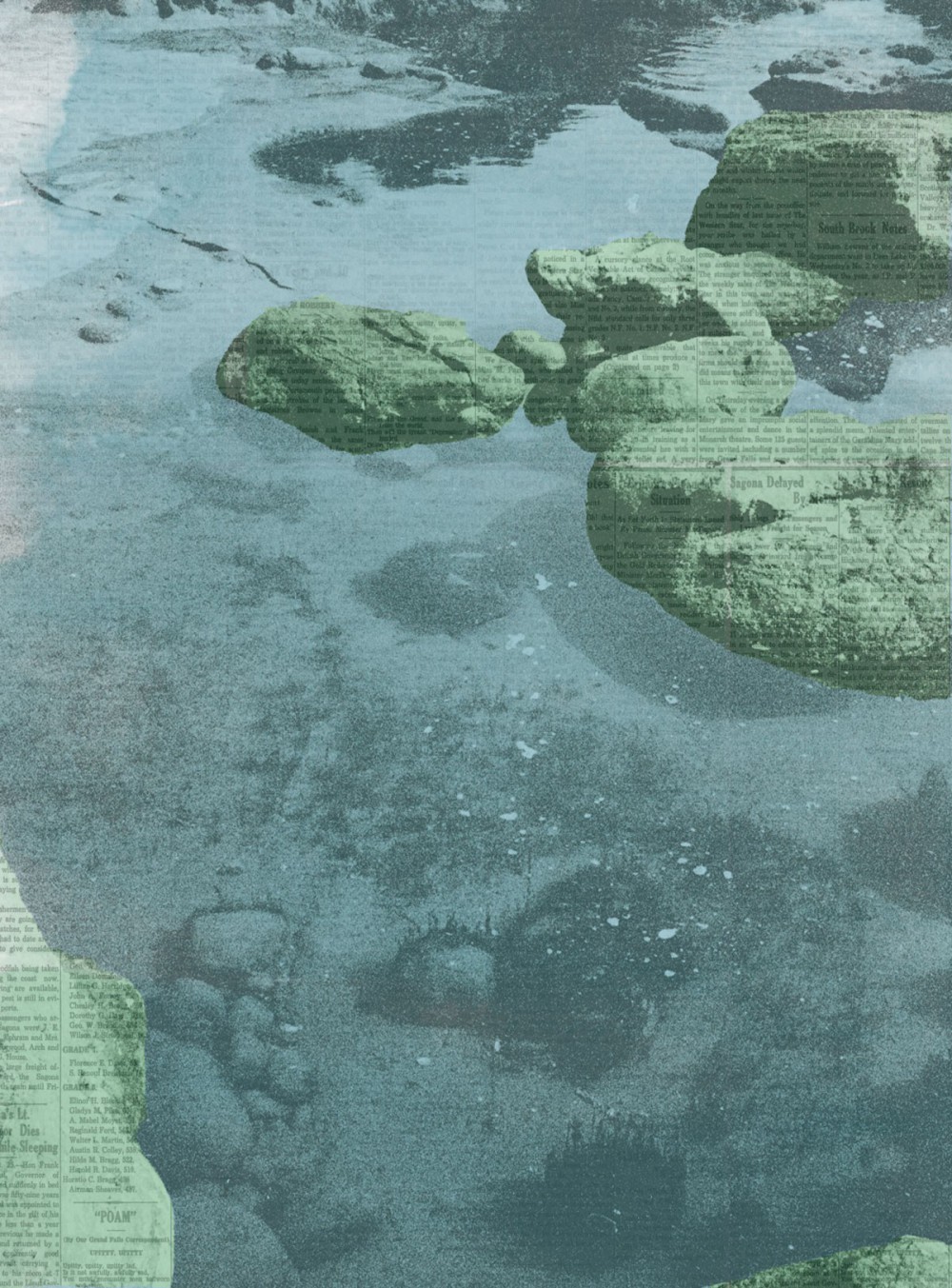

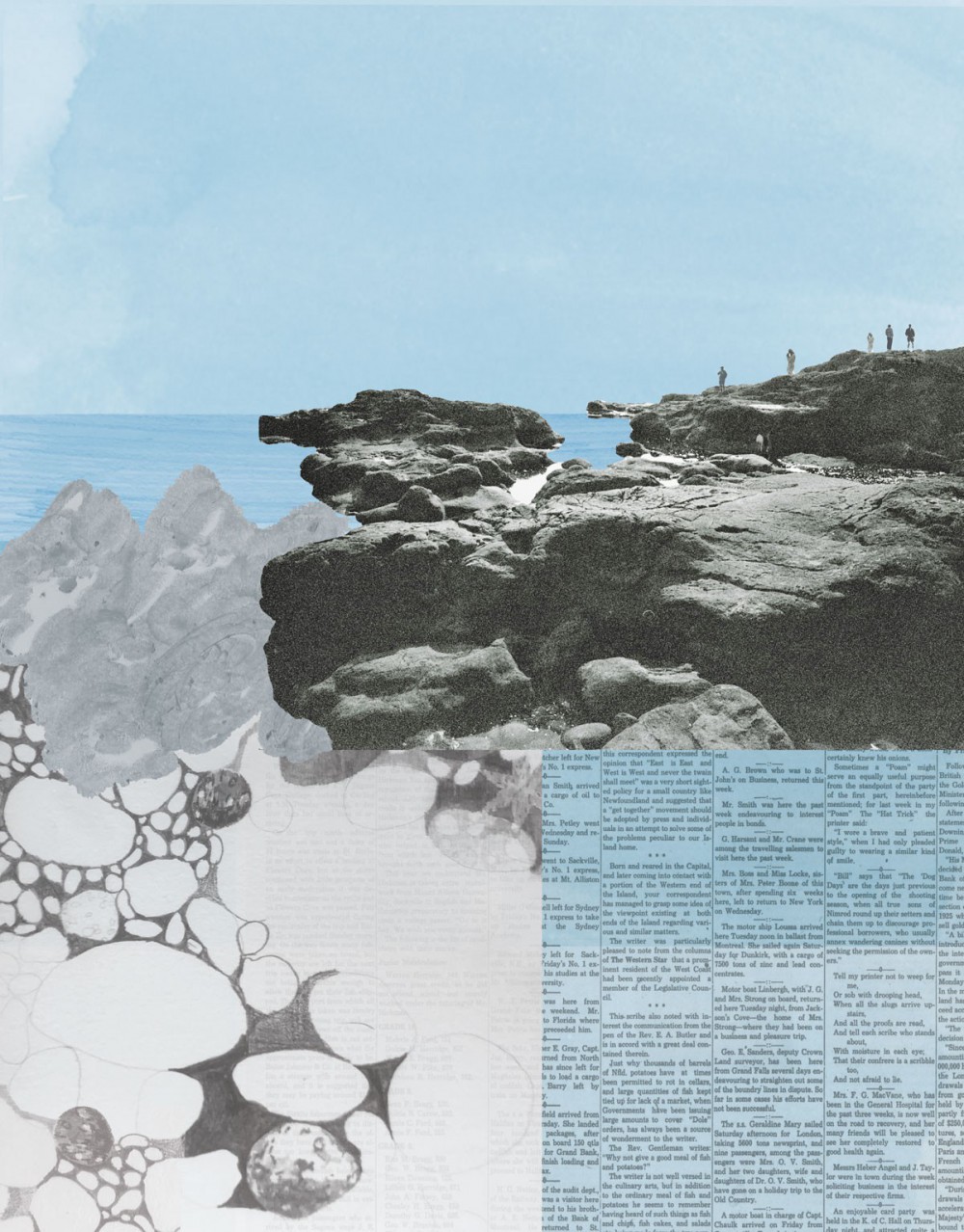

“We don’t get flooding in [this part of] Newfoundland because we’re rock and everything’s on a hill,” she explains. “But when you go up to Codroy Valley and you see 100 metres of cliffside have fallen into the ocean, and it’s getting progressively worse every year and now it’s just 100 metres from a home, and they’ve lost graves, and if the government doesn’t step in they’ll lose their homes,” that’s when she says climate change starts to feel relevant to people in Channel-Port aux Basques.

“You have to humanize [climate change], and you have to humanize it on a local level, and that’s where the paper comes in,” she adds.

The breakdown of local news

Recent shakeups in the East Coast’s media landscape have endangered the local reporting style that Roy describes as critical to effective coverage of the climate crisis.

In 2017, the publishers of Halifax’s daily newspaper the Chronicle Herald formed a new media company called the SaltWire Network and bought 28 local papers in Atlantic Canada, including one online publication, from Montreal-based company TC Transcontinental. At the time, SaltWire’s chief executive, Mark Lever, said the company had “no plans for cuts” and that the SaltWire deal would mean “not amalgamating. Not putting the same copy in every paper.” (The Chronicle Herald has a long history of labour disputes, and in 2016, Lever won RankandFile.ca’s infamous “Scumbag of the Year” contest.)

But over the past two years, Lever has done just that. SaltWire has shuttered several papers, merged more into new digital publications, shut down printing plants, closed local offices, sold or listed 10 buildings, centralized production in St. John’s in Newfoundland, put up paywalls for stories the company deems “premium content,” cut circulation of formerly daily papers, and expanded the areas that reporters are responsible for covering. SaltWire is also now suing TC Transcontinental, alleging the company misrepresented revenue streams.

SaltWire’s gutting of the region’s local newspapers is just one chapter in a longer history of news media consolidation in Canada. Since the 2008 financial crisis, 238 local papers have been shut down, representing 185 localities across the country.

The reasons a company gives are always similar: print media doesn’t work in a digital world, no one wants to pay to read the news anymore, that kind of thing.

For many, the process is intimately familiar: their local newspaper is bought by a media conglomerate and whittled down to a skeleton staff. It might be merged with several other papers into a single, free publication. More regional and national stories begin to seep across the pages of an ostensibly local publication. Production, editorial, all of it – layout, pagination, and printing – is centralized in a corporate headquarters. Countless jobs are lost. Eventually, the paper is shut down. The reasons a company gives are always similar: print media doesn’t work in a digital world, no one wants to pay to read the news anymore, that kind of thing.

But the real reason for this breakdown of local news media, says Patricia Elliott, a journalist and professor at the University of Regina who is seeking solutions to local news deficits, isn’t that readers are unwilling to pay for the news or read their local paper. These are red herrings, distractions from the real problem, which is the highly concentrated corporate ownership of Canada’s news media. And it’s these corporations, less concerned with questions of journalistic integrity and community issues than with bottom lines, that are to blame for the breakdown of local news.

“It’s media owners that make the work difficult and […] in Canada, our news media has experienced a complete regulatory failure for decades now,” says Elliott.

Canada has one of the highest levels of media concentration among all G8 countries, with a rate roughly double that in the United States. Of the remaining community papers in Canada, 599 are corporately owned, most of them by just five companies, the two largest being Postmedia and Torstar.

In 2015, when Postmedia bought the Sun Media newspaper chain, representing 175 publications, the Competition Bureau chose not to challenge the merger or hold public hearings. Instead, Elliott says, the bureau took Postmedia’s CEO at the time, Paul Godfrey, at his word that the corporation wouldn’t consolidate papers or make cuts. Within a year, Postmedia was merging and consolidating major newsrooms across the country.

“It’s media owners that make the work difficult and […] in Canada, our news media has experienced a complete regulatory failure for decades now,” says Elliott.

And just two years ago, in 2017, Postmedia and Torstar swapped ownership of 37 community newspapers and four free commuter papers. Then, citing declining ad revenue, the corporations shut down most of the swapped publications, leaving dozens of communities without a single paper. (At the time, journalists covering the merger pointed out that, one year prior, the five most senior executives at Postmedia received nearly $2.3 million in bonuses.)

“Big media conglomerates really don’t have the interest of local communities at heart. They’re there to maximize shareholder profits,” says Elliott. “And that makes a difference to climate change reporting – it’s the biggest story of our age and […] the only way you can make a story like that matter to people is if you frame it locally.”

“Reflecting reality back to its readership”

A local paper’s disintegration is felt in a community well before the paper is actually shut down, says Sarah Ladik, a former editor of several local newspapers who also worked as Roy’s editor after the SaltWire purchase.

As papers are consolidated, newsrooms lose the community-based resources and local context required to effectively cover climate-related stories. “It’s easy to cover a bad storm,” says Ladik. “It’s less easy to put the bad storm in a wider context, especially if you haven’t been there for 20 or 30 years.”

“And when you’re the only person at that office, or one of three covering the largest geographic chunk of Newfoundland, there’s not a lot of time for focusing on beats. And unfortunately, environment is the [beat] that gets pushed to the side the most often,” says Ladik, who has worked at local papers for her entire journalism career – including five that are now shuttered. (She jokes that she is the “grim reaper” of community news.)

“There’s not a lot of time for focusing on beats. And unfortunately, environment is the [beat] that gets pushed to the side the most often.”

When community papers are unable to report on the local dimensions of the climate crisis, those stories often get under-reported by regional or national outlets or, more often than not, simply ignored.

“I’ve spoken with residents before that have tried to reach out to CBC or NTV news or the larger media and they’ve been flat out rejected,” says Roy. In one instance, a couple in the Codroy Valley contacted Roy about a series of persistent power outages they were experiencing – over 169 in just 3 1/2 years – as a result of increasingly regular hurricane-force winds.

“They tried to reach out to larger media who weren’t interested,” Roy said. “They came to me and said they were having this trouble – ‘we’ve tried CBC and they don’t want nothing to do with this.’”

Roy drove to Codroy Valley to interview the couple at their home, then called Newfoundland Power. She later published an article in the Gulf News detailing the power outages and the couple’s frustrations with the power company. “Within a week, they were on CBC Radio,” she said.

Curtis argues that local papers are often the primary way rural communities “reach out to each other” about climate-related issues.

A local paper ensures that the “voices of rural communities [are] heard in the provincial capital and [are] being addressed,” Curtis says. Corporate ownership and consolidation of local news “drastically diminish” a community’s capacity to escalate its stories and concerns to broader audiences or political decision-makers, he argues.

The regional or national news media options available after a local paper shutters “are not going to inform you about what’s going on in your community,” Ladik says, adding that local papers “have a huge role to play in reflecting reality back to its readership.”

Of course, there is no single “reality” or perspective for any one community. Reality is contested, and, when functioning well, local papers play a critical role in providing a venue for this contestation to unfold.

It’s this reflexive capacity that allows a local paper to serve as a community forum, a role that Ladik says editors achieve by publishing a diversity of op-eds and letters to the editor, and by making editorial decisions that represent their readers.

As a forum, local papers provide communities with accessible platforms to shape and debate the news, discuss ideas, and contest opinions. In doing so, editors offer people “a chance to make their arguments heard,” says Curtis. “These arguments take their natural course against each other,” impacting local politics and shaping public narratives along the way.

Unlike social media, local papers are tied to a specific place, to a specific community. Opinions and conversations expressed in a community’s paper are less easily manipulated or distorted than those shared online; are accompanied by a certain amount of shared context and background, often lacking on social media; and can serve as an unalterable record when accountability is needed.

To perform this role well, papers require a community’s trust. And for local papers, trust and reliability typically boil down to actually knowing the publication’s reporters and editors.

“You’re not anonymous. People recognize you, they know who you are. I’ve had people come up to me and shout at me about stuff I’ve printed, in the grocery store,” Ladik says. (Someone threw an orange at her once.)

Readers feel like their local papers can “be held more accountable to the people in the community rather than something that’s brought in at a national level,” says Curtis.

By divorcing a paper from the community and moving editorial decision-making to a centralized headquarters, away from the community, corporate media owners erode this vital sense of trust and rudimentary accountability mechanism.

Moreover, when editorial decisions are outsourced, the opinions and ideologies reflected in a local paper are not only unrepresentative of a community, they are also subject to severe conflicts of interest. For example, in a leaked presentation in 2013 it was revealed that Postmedia, the corporation that owns many of Canada’s local papers, entered into an agreement with the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers, the oil industry’s main lobby, to “amplify” an energy mandate by “all means editorially, technically and creatively.”

As local papers shutter, issues like climate change lose their relationship to place and community, and they begin to “seem out of [the community’s] control and don’t seem like something that can be dealt with,” Curtis says.

The case of Corner Brook

When a local media ecosystem functions well, communities are often afforded more direct participation in the public process.

In 2013, a mining company called Thomas Resources was seeking approval from the City of Corner Brook, which has about 30,000 people, to conduct exploratory drilling near their watershed.

That year, Curtis was working with a group of activists to publish a zine called The 4 O’Clock Whistle, a grassroots publication with roots in the Occupy movement and named after the town’s pulp and paper mill, which “whistles” daily at 4 p.m. The activists behind The 4 O’Clock Whistle, many of them students at the Grenfell Campus of Memorial University, published stories about community organizing around social and environmental issues in Corner Brook.

Curtis had become involved with The 4 O’Clock Whistle after what he described as a “massively successful citizen’s movement” against hydraulic fracking in the region. The zine’s investigative coverage of the fracking debate – specifically about two proposals from companies Black Spruce Exploration Corp. and Shoal Point Energy Ltd. – provided a progressive, critical counterbalance to the local news media’s coverage of the issue.

“We felt like voices weren’t being captured, or we felt that generally that there was a lack of environmental criticism happening,” Curtis explains. “We saw specific areas where there needed to be more investigation.” Hot on the heels of the fracking debate, Thomas Resources’ 2013 drilling proposal was one such area.

The community’s local newspaper, the Western Star, was reporting extensively on Thomas Resources’ proposal to drill 21 holes near the watershed, where it would explore for garnet and kyanite.

Western Star reporters chronicled a contentious public consultation process: city council’s decision to delay a vote on the application; information sessions held by the company; news that two outspoken city councillors opposed the proposal; the Grenfell student union’s stance against the proposal; an incident where a local company hired by Thomas Resources, Newfoundland Hard-Rok Inc., admitted to leaving trash near the water supply; the launch of a new Thomas Resources website; the mayor’s support for the proposal; and more.

The paper also published a handful of reader polls and over a dozen op-eds and letters to the editor both in favour of and against the proposal, including letters from a city councillor, a Thomas Resources representative, and Corner Brook’s mayor at the time, Neville Greeley.

As with during the fracking debate, “there would be letters to the editor back and forth on the issue; you’d see those fights are happening. It was a bit like stepping back in time, where there’d be one editorial one day and the next day there’d be a rebuttal,” says Curtis.

While many residents and residents’ associations stood in favour of the proposal, citing job creation and economic development potential, residents also used the pages of the Western Star to voice serious concern about environmental impacts on the watershed.

On March 13, 2013, Glen Keeling, a representative of the Grenfell Campus Student Union, penned a letter in the Western Star in response to a letter the paper had run the day earlier by Rod Mercer, the Thomas Resources representative.

Keeling writes that, in a meeting between Thomas Resources representatives and the student union, company reps stated that “the ultimate goal of this project was to develop a quarry. Models for jobs and revenues were based on 100,000 tonnes of processed product a year.”

Five days later, Mayor Greeley called in to a daily talk radio show called “Backtalk with Paddy Daly” on Voice of the Common Man, a widely popular AM radio station in Newfoundland. On Backtalk, Daly discusses with callers their opinions on local issues. “I reduce politicians’ access as much as possible. I’m much more interested in hearing from everyday people,” Daly explains. (Though Daly says it’s been “well documented” that the program has an impact on government: “I can have an elected official contact me within minutes of hearing something that’s on the air,” he says.)

Their conversation lasts for just over 13 minutes, with Daly grilling Greeley on controversial aspects of the proposal. Throughout the call, Greeley sounds frustrated, even irritated, with the growing opposition to the proposal. (“They’re against cutting down a tree, they’re against catching a fish, they’re against turning over a stone,” he says to Daly.)

The controversy over the proposal was only just beginning. Around the same time, a source leaks a letter to The 4 O’Clock Whistle that had been written by then-Mayor Greeley to the president and all members of the Greater Corner Brook Board of Trade (GCBBT). In the letter, Greeley urged the GCBBT to “take a positive position” on the proposal.

The 4 O’Clock Whistle published the letter, pointing out that the phrasing of Greeley’s letter contradicted his promise to stay neutral on the proposal until after the public consultation process.

Five days later, the Western Star reported on the letter, though without mentioning The 4 O’Clock Whistle. “I don’t think that was appropriate for a man in his position to ask us to do that,” the president of the GCBBT is quoted in the Western Star article. Picked up by the community’s main source of news, the letter exacerbated the already hot debate over the proposal, which after several unsatisfactory public information sessions and dissent from two prominent city councillors, was already starting to be seen as politically fraught.

Fast-forward several months and the Western Star breaks the news that Thomas Resources had withdrawn its drilling proposal and had no plans to pursue it further. Greeley is quoted in the Western Star saying that he believed widespread community opposition to the proposal played a role in the company’s decision.

The Thomas Resources proposal was “an incredibly complex issue with a lot of different components [and] a lot of misinformation promoted by industry,” Curtis says. “But […] by the sheer will of people in the community, we were able to counter that misinformation.”

The proposal itself was “comparatively small” by development standards, says Stephan Walke, a former contributor to The 4 O’Clock Whistle. But having more than one publication reporting on it and showing up to public consultations gave residents – as well as Thomas Resources representatives – the impression “that there [was] more media in a small place, and that there [was] a diversity of media,”

Walke explains. “Having that presence in itself can make people think harder about what the importance [of a project] is,” he adds.

From the Thomas Resources proposal emerges a broader story about the role that local news media plays in environmental activism. While it’s hard not to see the The 4 O’Clock Whistle’s investigative work – particularly the leaked letter – as the catalyst to the opposition and eventual defeat of the Thomas Resources proposal, Curtis describes both the Whistle and the Western Star as integral to the effort. Their relationship, he explains, was “mutualistic.”

“Even though we were a smaller volunteer publication, [our stories] would almost always get picked up a bit by the Western Star,” Curtis says. “We were helping to bring light to specific topics and then the paper was following through on that in a way that we couldn’t.” The interplay between Corner Brook’s local newspaper and grassroots media stimulated deeper public discourse around environmental issues.

This past April, SaltWire Network, which acquired the Western Star in its deal with TC Transcontinental, reduced the paper’s circulation from a paid-for daily subscription to a free weekly publication, fired at least 30 employees, moved production to SaltWire’s central facilities in St. John’s, and expanded the paper’s footprint. Just eight people held on to their jobs. This news is “devastating” to the community, Curtis says.

“What kind of media do we turn to to cover everyday, so-called mundane, not the sexiest issues or meetings? Like a council meeting,” says Daly. “You won’t get CBC or the National Post at a small town council meeting where some of the biggest decisions affecting your everyday life are made.”

“A better way”

Thousands of kilometres away, journalists and communities on the West Coast are struggling to navigate the same fractures in their local media landscape. “Traditionally, local news only focused on things that had local impacts that basically ended at the barriers of whatever jurisdiction they covered,” says Geoff Dembicki, a journalist who has worked as a reporter with The Tyee, a British Columbia-based online publication that focuses on environmental news in Canada. “But as we see with climate change, that [distinction] is just not the case anymore.”

Independent publications like The Tyee impart a deeper, global understanding of climate change, but Dembicki says that local newspapers, tied to place and community, are still important. He cites the battle against the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion, in which local paper Burnaby Now played a foundational role in activating the community.

“Residents had a bunch of concerns about the physical impact [of the pipeline terminal in Burnaby] – the safety, whether it was good to have more tankers in the harbour,” he explained. Burnaby Now’s reporting “created this baseline intensity around the project, which helped make that larger opposition possible.”

“Traditionally, local news only focused on things that had local impacts that basically ended at the barriers of whatever jurisdiction they covered. But as we see with climate change, that [distinction] is just not the case anymore.”

With scientists saying we have just 11 years left to curb climate breakdown, reporters and climate activists seem to be converging on the view that local news needs to break free from consolidated corporate ownership if the media want to keep covering the climate crisis in a way that resonates with communities.

Some local journalists are experimenting with new models, trying to find ways to make sure this need is met.

In 2018, Postmedia shut down the local Kapuskasing Northern Times in northern Ontario. “When the paper shut down, it really as far as I’m concerned had become a shell of its former self,” says Kevin Anderson, who had worked at the paper for nearly his entire career, starting as a sports writer and eventually becoming the paper’s managing editor.

The paper’s operations and production had been centralized, and much of its news, including editorial, was focused on regional or national issues. (Postmedia’s conservative political slant was especially irksome to the community, which Anderson describes as “very decidedly NDP” and “proudly blue-collar and rightly so.”)

Working within a corporate structure frustrated Anderson – “I had orders coming from people who didn’t even know where this town was” – and readers complained about the paper’s lack of local coverage.

“Anyone in the print media industry knows that page count is directly correlated with advertising content. And if the ad support wasn’t there, the paper was very often small,” he says. But “people didn’t care they were getting it for free – they wanted more. And I frankly don’t blame them,” says Anderson, who, by the time the paper had closed down, was working with just one other reporter to cover an area of about 145 kilometres.

When the Northern Times shuttered, Anderson got together with a group of local journalists and launched the Community Press/La Presse Communautaire, a locally owned and operated non-profit publication. Anderson received seed financial support from the local francophone radio station, Radio Kap Nord Communications, Inc.

“I had this nagging idea that there was a better way,” he says. Anderson wanted the publication to be “all local, all local, all the time. Not a single piece of editorial content that came from outside our catchment area.” Anderson’s new publication would also be in both English and French, reflecting a community which is 70 per cent bilingual.

When I spoke with Anderson, the publication was on the verge of shutting down. Despite its popularity in the community – “I don’t go a day where I don’t have at least three or four people stop me and thank me for starting the new paper and tell me how much they love it and that it’s all local and they can read it in the language of their choice,” he says – production of the Community Press proved difficult to sustain financially. On May 30, Anderson was forced to suspend operations indefinitely.

“My biggest fear, and it’s unfortunate that it comes to this, is what’s going to happen when this paper disappears,” Anderson said at the time. “I’m sure a lot of people are going to be very, very upset.”

Despite having to shut down the Community Press, Anderson remains optimistic about the future of local journalism in Kapuskasing: “Now [that the community] ha[s] a paper they have a sense of ownership in, I gotta believe they’re not gonna let it go.”

Note: This article previously stated that The Tyee is a not-for-profit publication. In fact, it is a for-profit publication.