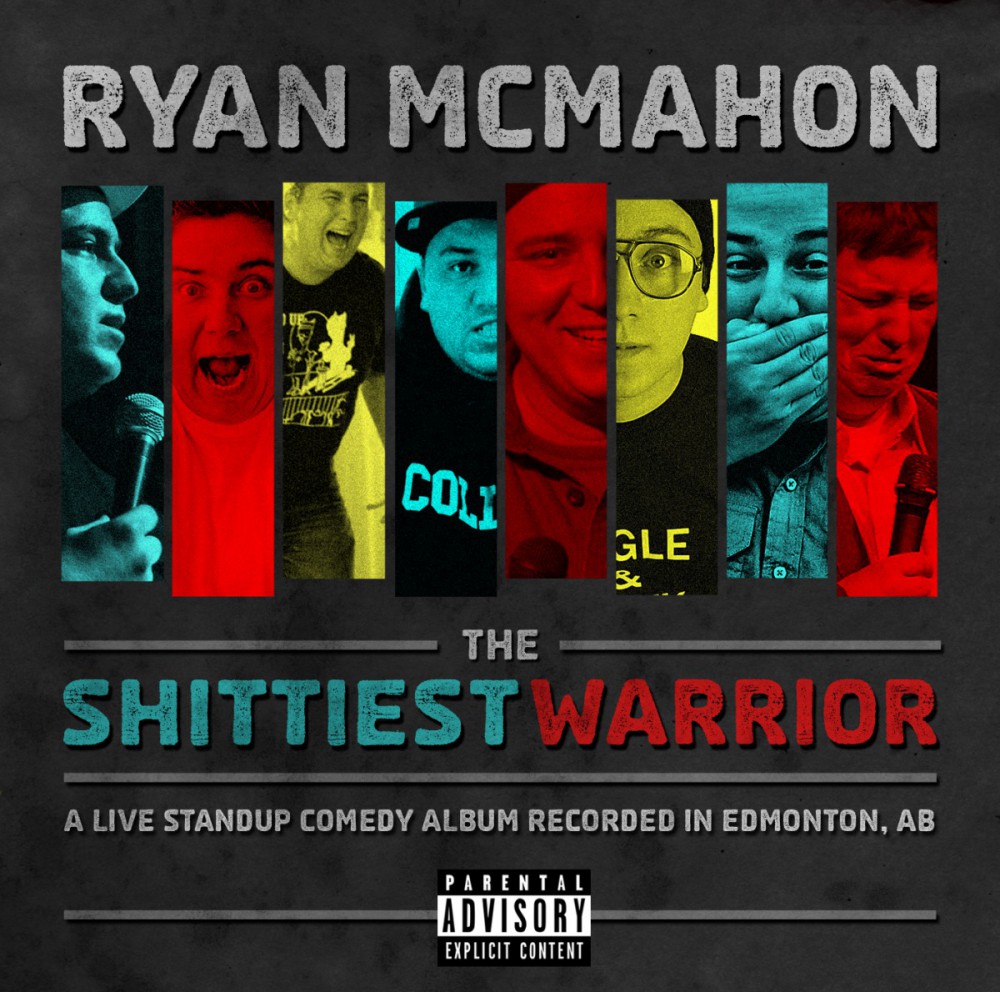

These days, when a comic takes aim at political issues, they assume a disposition of detached arrogance. Condescension (from a safe distance) is the shtick to which we are now habituated. The style is easy and stale, which is why Ryan McMahon’s album, The Shittiest Warrior, is so refreshing and original. McMahon is engaged. He is not that jaded satirist who passively mocks society from self-assumed heights. The Shittiest Warrior is uniquely entertaining because it comes from a place of restless honesty that refuses to indulge in charming but ultimately un-invested self-depreciation and social critique. McMahon takes it personally and his struggles make you laugh. He is a native comic who cares deeply about Indigenous issues. But, as he tells us, he also has man-boobs. He is genuinely pissed off about injustice. He grounds himself in his traditions. But he also prefers Indian buffet to the uncertainties of fishing, and therein lies the absurd predicament that he unpacks before us in The Shittiest Warrior.

McMahon delivers his reflections on racism and colonialism, all perfectly punctuated with hilarious bouts of fury over grocery checkout dividers, muddy pick-ups, and truck-nuts (those huge fake balls that super sexually confident men put on their truck hitches). When not challenging red-necks to combat, he ruminates on his paralyzing self-doubt over career choices, fatherhood, getting fat, joke endings, hitchhikers, and a mysterious buffalo that refuses to acknowledge him during a time of need. McMahon paints us a picture of himself shirtless on horseback. And if that isn’t ridiculous enough, try McMahon gasping for air in a woman’s maternity bathing suit.

McMahon of course follows greats like Charlie Hill in tackling Indigenous politics through humour. He is unique, however. His work is informed by the same kind of penetrating political insight that George Carlin deployed with such force, yet he keeps all of that in the background. In The Shittiest Warrior, McMahon chooses to foreground the question of what a ridiculously normal person could possibly do in these absurd conditions. Comics almost always focus on deconstructing only one of these aspects: the person or the conditions. But McMahon’s material is uncharacteristically alive to both. The wit here is anything but passive. He doesn’t invite us to either laugh at his follies or take up some self-satisfying vantage over and above the political fray. Rather, McMahon’s stories lead us into that preposterous space between truck-nuts and man-boobs, between the insufferable and the suffering. Good stories make you laugh. Great stories live in your soul because they matter. Ryan McMahon’s stories matter. You are not simply warm and satisfied by the end of it; you are motivated.