In 1936, the president of the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union (ILGWU) dispatched Rose Pesotta, one of his most successful labour organizers, on an urgent mission: to organize the dressmakers of Montreal. Pesotta was told to look out for the “midinettes” – a portmanteau of midi (noon) and dinette (light lunch) that Montrealers used to refer to the French-Canadian girls who would pour out from the downtown dress factories during their brief lunch break.

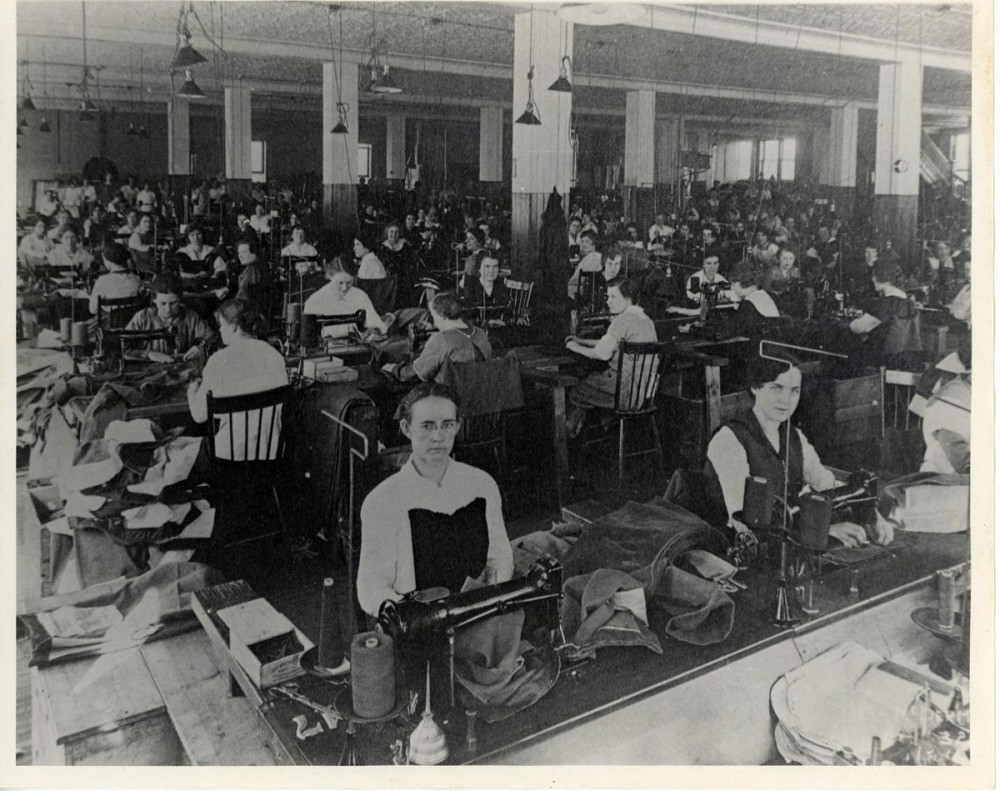

“Sun and air were commodities quite foreign to garment workers,” noted Aldea Guillemette, a member of the ILGWU. “When they did leave their shops briefly at lunch-time, people walking along Mount Royal Avenue or St. Catherine or Bleury streets must have been amazed that so many human beings could be squeezed into two- and three-room factories.”

In the 1930s, the dress industry was made up almost exclusively of French Canadian women. The midinettes worked up to 80 hours a week in sunless factories, where they faced the deafening roar of machines and the unwanted sexual advances of their foremen. In return, they brought home between about $5 and $8 a week.

Despite these gruelling conditions, the midinettes were considered unorganizable. “You’ll never organize girls – especially the girls in the Province of Quebec,” Bernard Shane, manager of the ILGWU, was repeatedly warned.

——

The situation Pesotta faced reveals the exploitative history of Canadian Confederation and the new era of industrialization it unleashed on the country.

Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels wrote, “the need of a constantly expanding market for its products chases the bourgeoisie over the whole surface of the globe.” Confederation ensnared the fragmentary economies of the Quebec, Ontario, and Maritime colonies into a single market for the new industry exploding in Montreal, Hamilton, Toronto, and Winnipeg. New railroads, canals, and roads paved the way for the smooth flow of capital from the city into the colonial hinterland, where it displaced the craft production and small-scale manufacturing there with the city’s mass-produced commodities.

Montreal quickly rose as the centre of industrial production in Canada. Not only was it a strategic port, it also had a unique resource: an abundant supply of cheap French-Canadian women’s labour.

Montreal quickly rose as the centre of industrial production in Canada. Not only was it a strategic port, it also had a unique resource: an abundant supply of cheap French-Canadian women’s labour to propel the city’s textile, rubber, and clothing industries.

The city’s labour force was starkly divided along linguistic, gender, religious, and ethnic lines, and French-Canadian female workers found themselves at a nodal point in these divisions.

The Catholic Church dominated all aspects of francophone life. Sunday sermons demonized the Jewish-led unions and urged parishioners to seek charity solutions to their troubles or to join their own compliant Catholic unions, which Pesotta spurned as “company unions.” One union organizer recounted, “The very same women who were militants in the shop were under the influence of the Church and the priest at home. In one shop strike … we got a raise of $2.50 a week. Then on Monday, the women came back to the office to tell us they were going to give the money back to the manufacturers because the priest had told them at Sunday mass that the money was sinful money.”

Manufacturers from across North America preyed on this cheap and compliant labour force. “No where are there found people better adapted for factory hands, more intelligent, docile, and giving less trouble to their employers, than in Lower Canada,” the Montreal General Railroad Celebration Committee assured prospective manufacturers in 1856. Given that Montreal was one of the only industrialized francophone cities in North America, the women could not easily move elsewhere in pursuit of higher wages. “You know that Irish women … if they come to this country and do not get the wages they want, will emigrate,” averred a Montreal clothier at the Select Committee on the Manufacturing Interests of the Dominion in 1876. “The French women do not emigrate, and therefore we have that class of labour in the Province of Quebec.”

The confinement of these women amid this explosion of enterprise signals one of the central contradictions of capitalism: its uneven expansion. Despite capital’s need to “nestle everywhere, settle everywhere, establish connexions everywhere,” to use Marx and Engels’ words, it also creates barriers that choke off the power of labour.

As the garment industry intensified, the tyranny of the church as well as ethnic, linguistic, and religious divisions prevented solidarity and collective action within the labour force.

The divisions cut across gender lines as well. The subordination of women in the family set the mould for subordination in the factory. In garment factories, men worked in “the aristocracy of the trade” as cutters and pressers, while women were employed as sewing machine operators. Heavy machines required skill and dexterity to manoeuver – a supposed deficit among women. Of course, these categories were meaningless, as they had no relation to actual strength, dexterity, or skill capacity. One factory inspector conceded that although women’s work was “generally regarded as light,” in reality it was “hard and most exacting. Women engaged in it are liable to have to work overtime more frequently than in other trades.”

Labour leadership itself was dominated by skilled male workers who were often English-speaking and Jewish. Although rank-and-file female union members were expected to participate in workers’ strikes, they were often excluded from decision-making. These union leaders saw themselves as “father figures” for union activity in the garment industry – not as peers or comrades.

The paternalism reflected a deep division between the skilled male union leaders and the “unskilled” female base. Unsurprisingly, many women were skeptical about joining the union. As historian Mercedes Steedman points out, “[T]he union offices were places for men to gather, play cards, and talk politics. Only at strike time did the union halls open up their doors to women workers and provide gathering places and social activities that women were able to plan and participate in.” These regular reminders that organizing was not for them did the work for manufacturers of keeping the workers divided.

——

“The dressmakers needed a woman’s approach,” Pesotta insisted when she arrived in Montreal in the fall of 1936. She corralled a team of francophone women to help lead the union. Léa Roback, a renowned feminist syndicalist fluent in Yiddish, English, and French, served as the director of the educational department and trained the midinettes in union activism. As part of the education strategy, the organizers offered the dressmakers language classes, as well as courses on a wide range of subjects including journalism, music, public speaking, and the history of the Canadian labour movement.

Drawing from her experience organizing in Puerto Rico and Los Angeles, Pesotta created a coalition across gender, ethnic, and religious lines in Montreal. ILGWU became a cultural hub for social activities such as a choir, orchestra, theatre, sports, as well as parties and festivals popular with French Canadians. With Pesotta’s strategic framing and education, this cultural infrastructure cemented the understanding that, as one garment worker put it, “the enemy is never another worker, it’s the factory, the boss.”

In January 1937, the dressmakers received their first charter, authorizing the creation of ILGWU Local 262. On their agenda was to form a contract with manufacturers that ensured union recognition, and better hours and pay.

Five thousand mostly French-Canadian female dressmakers brought the Montreal garment industry to its knees in the most momentous strike in Canadian dressmaking history.

But the Montreal Dress Manufacturers’ Guild – an association of factory owners – refused to recognize the union. On April 15, 1937, mere months after organizing, the local, demanding recognition of the union, a 44-hour workweek, and time-and-a-half overtime pay, triggered a surprise general strike. Five thousand mostly French-Canadian female dressmakers brought the Montreal garment industry to its knees in the most momentous strike in Canadian dressmaking history.

In response, manufacturers, the church, and the government colluded to crush the women. Montreal’s high clergy called for the deportation of Pesotta. The Duplessis government’s ferocious anti-communist campaign criminalized any form of labour activism. And the rampant red-baiting of the day often took the form of anti-Semitism, as newspapers such as La Nation and Le Devoir condemned ILGWU organizers as “la juiverie internationale” or “the international Jewry” – a label reflecting the long history of anti-Semitic representations of Jews as a menace proliferating globally through finance or, contradictorily, communism.

But the midinettes maintained their solidarity. As one picketer’s sign declared, “nos races sont multiples, notre but est un” – “we are many races, but our aim is one.” Unified, they deprived the manufacturers of their labour power, forcing them to finally enter into negotiation with the strikers. And on May 10, after 14 hours of negotiation, the strikers won.

This year marks the 80th anniversary of the ILGWU Local 262 strike – an event that historians continue to laud as a milestone in Canadian women’s history.

But these tributes often fail to mention that soon after the workers returned to work, employers began to ignore the new contract. The ILGWU was weakened by its own internal anti-communist purges, which pushed out both Roback and Pesotta in an effort to preserve its social democratic politics and appease the red-baiters of the day.

——

In the years since, the garment industry’s exploitative factories have not been abolished – they were merely exported to the Global South during the deindustrialization of the 1960s. Today’s midinettes are the egregiously underpaid young women in countries like Bangladesh, Cambodia, and Haiti, where Canadian corporations exploit weak labour rights and jeopardize the health and safety of workers.

A century and a half after Confederation, the Canadian state remains committed to elite economic interests. Canada has signed trade deals that undermine labour rights abroad and deregulate labour laws at home. Eight decades after the midinettes took to the streets, women continue to face distinct precarity as they shoulder reproductive labour, unequal pay, and sexual harassment or abuse at work. As the country celebrates its 150th birthday, we would do well to remember that our most enduring bonds lie not with the nation, but with workers around the world.