From classic theoretical texts to the constant news cycle, leftists read a lot. While the reading is fundamental, it can be dense and time-consuming. Thankfully, there are so many ways to engage with leftist politics. Graphic novels provide opportunities for alternative leftist engagement. In this reading list, I recommend five literary graphic novels that explore urban dispossession, domestic labour, worker alienation, resource extraction, and social reproduction.

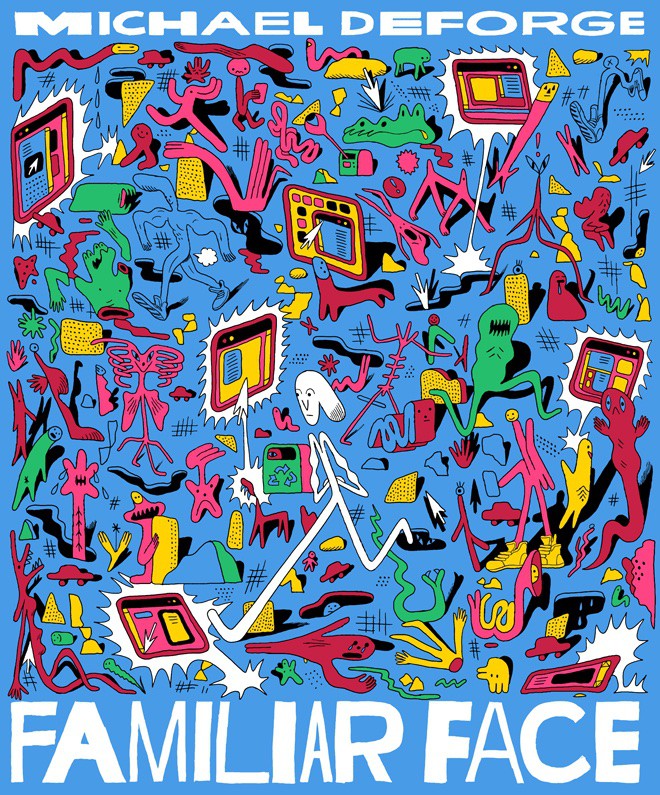

Familiar Face (2020)

Familiar Face illustrates the relationship between technocratic ideals and autocratic governance. In DeForge’s hyper-futuristic, interoperable city, nothing and no one is immune to the algorithm. Bodies and buildings change rapidly without notice or consent. Familiar Face shows readers what happens when we submit to unregulated automation: we lose recognition of and control over our communities and ourselves.

With loud colours and exaggerated proportions, DeForge cleverly satirizes the Corporate Memphis aesthetic. Tech companies use this cartoonish aesthetic to mask their role in creating inhospitable urban infrastructures and defunct social grammars. In doing so, DeForge invites deeply personal questions about the future. What does the future feel like? Does it feel good? Familiar Face brings readers back into their bodies, urging them to find both social and political connection.

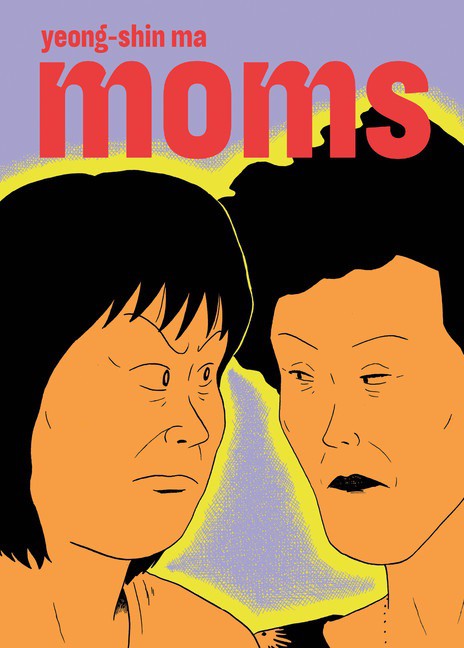

Moms (2020)

Ma provides substantial historical context throughout this fast-paced story. Reading Moms feels like watching a soap opera or a reality show – full of secret affairs and dramatic betrayals. The main mom, SoYeon, cleans public bathrooms to pay for her estranged husband’s gambling debts, her lover’s drinking habit, and her son’s musical ambitions. Throughout Moms, Ma ingeniously embeds wacky scenarios with critical insights into the everyday trade-offs for working women. Come for drama – stay for the astute feminist economic analysis.

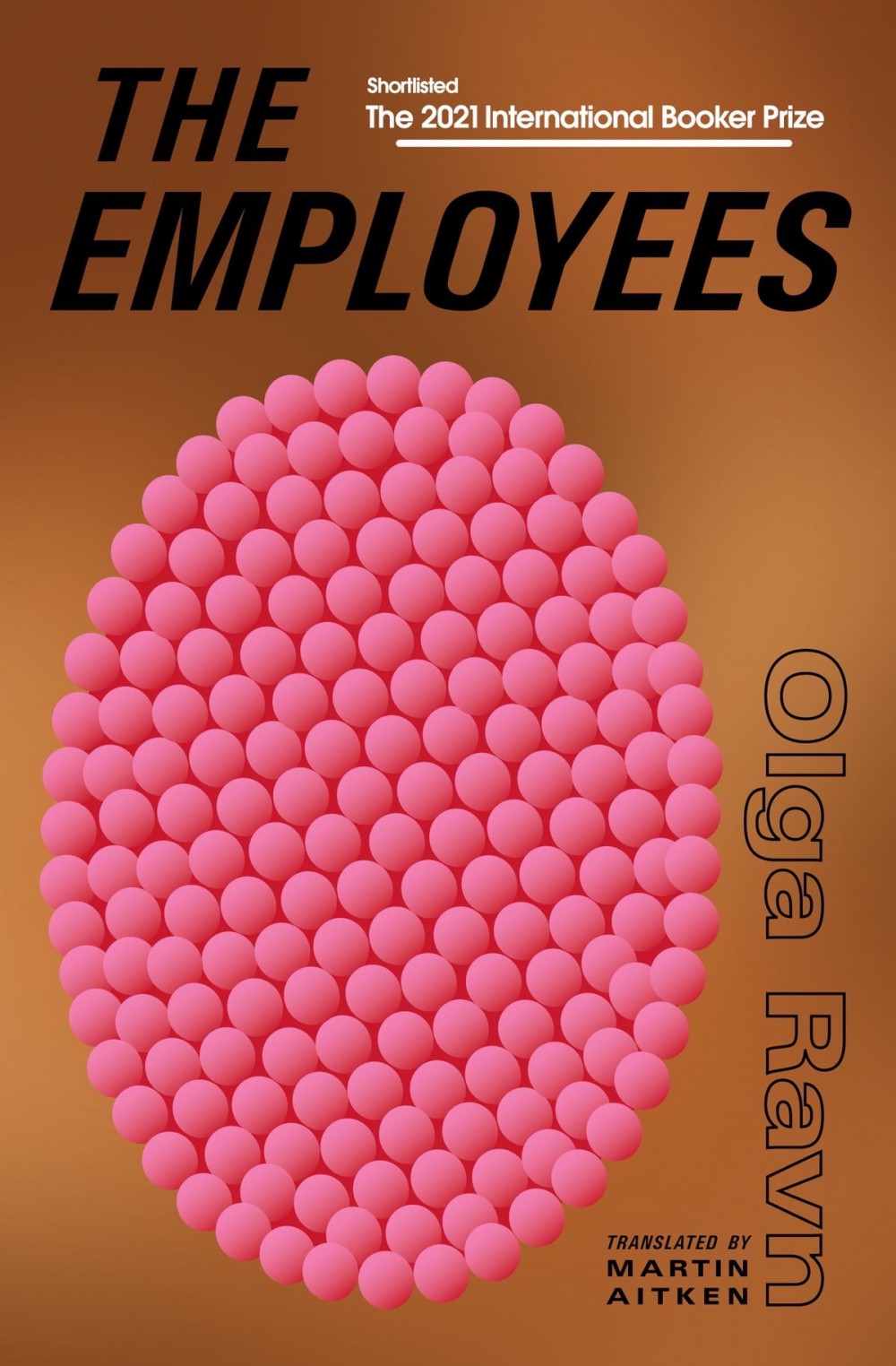

The Employees (2020)

Ravn emphasizes the affective processes underlying collective action, creating impeccably faithful renderings of the long-term and embodied impacts of the wage relation. The Employees compels readers to reflect inward. How does the working day make us feel? How do we identify with and organize around these shared experiences? Ravn connects individual emotional conflict with broader political struggle. The Employees is a powerful exercise in identifying shared experiences, naming complex emotions, and translating them into collective action.

Ducks (2022)

Beaton dissects institutional narratives that pit the environment against the economy. As Beaton reflects on her lived experiences, she understands this conflict differently – between those who reap the profits and those who bear the burdens of Canada’s resource economy. On one side there are oil executives conducting rare site visits in the most expensive protective equipment, and on the other there are Indigenous communities, Indigenous women, workers, and ducks on the front lines of extractivism. Beaton encourages us to interrogate these institutional narratives and work toward unlikely but necessary political coalitions.

Bastard (2018)

Amid all the R-rated action, de Radiguès poses timely questions about social reproduction under late capitalism. Bastard investigates the absurdism of our hyper-marketized capitalist reality, which conflates individual failures with systemic state and market failures, such as unaffordable housing, unemployment, and inflation (or rather “greed-flation”). Neoliberal justifications dictate that chronic socio-economic precarity is an outcome of individual moral failures. While this capitalist reality advocates for Protestant work ethics (and aesthetics), it consistently privileges and prioritizes social class. May and Eugene are skilled and capable workers. However, they continue to hop from job to job and from town to town. Bastard reckons with the paradoxical logics of these Protestant ethics: we make massive financial and emotional investments into working hard and making sacrifices, yet we continue to struggle to provide for ourselves and our communities. It takes a lot to realize that it’s not you. It’s capitalism.

_1200_675_90_s_c1_.jpg)