As I write this, the average market rent for a one-bedroom apartment in Toronto is $1,200. Nearly half of the city, 47 per cent, spends over a third of their income on rent, meaning that – without dipping into savings, which many don’t have – they are one missed paycheque away from losing their homes or going without food.

Of Toronto’s homeless population, over 11 per cent are two-spirited, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and/or queer (2S-LGBTQ). Among youth, that number ranges from 24 to 40 per cent, depending on which researcher you ask. Just about every report on the subject finds that poverty disproportionately impacts queer and trans people, especially when they are Black, Indigenous, or people of colour. Being poor opens them up to greater violence and harassment by police. It reduces their employment opportunities and access to health care. It pushes them into shelters or other unsafe living situations, where they encounter discrimination and sexual violence from straight and cisgender staff and bunkmates. In every sense that matters, poverty is an 2S-LGBTQ issue.

So why aren’t mainstream Canadian 2S-LGBTQ organizations treating it as such?

Of Toronto’s homeless population, over 11 per cent are 2S-LGBTQ.

Egale is Canada’s only nationwide 2S-LGBTQ charity. They helm an annual awareness and fundraising drive around the issue of 2S-LGBTQ homelessness that focuses nearly entirely on homophobia and transphobia as the causes of obscenely high homelessness rates among 2S-LGBTQ youth. Egale works on improving education and training among shelter staff and case workers, and it provides some support to individual service users who access the organization or its partners. It has also provided vital support to a small shelter specifically for 2S-LGBTQ youth in Toronto.

Beyond that, however, their strategy is remarkably apolitical. They offer information and resources but do not engage with 2S-LGBTQ homelessness as a problem of poverty, let alone with poverty as a political issue – one produced by and through various market and structural practices. In this way, Egale resembles many other mainstream organizations of their ilk, which across the board fail to articulate the risk of violence for 2S-LGBTQ people, both as a symptom of their intersection with poverty and as connected to specific policies and practices carried out in the interest of capitalists and capital accumulation.

Egale has fallen into one of the more common traps of 2S-LGBTQ non-profit organizing. While well intentioned and certainly useful, their activism primarily represents the perceptions and interests of more privileged members of the community – those who do not deal directly with homelessness, substance abuse, sex work, and other, more “unseemly” elements of 2S-LGBTQ life, which has historically largely been defined by its lack of access to capital.

What would a coordinated response to 2S-LGBTQ homelessness require? For starters, it would entail wholesale changes to multiple local shelter systems, consultation on a national housing strategy, advocacy against gentrification and predatory development, organizing alongside anti-racism and anti-poverty activists, protests against austerity budgets that reduce mental health services for those most at risk, staffing at overdose prevention sites, apartment-hunting training for youth and newcomers, and support for unions and striking workers – to name just a few key strategies.

In this way, Egale resembles many other mainstream organizations of their ilk, which across the board fail to articulate the risk of violence for 2S-LGBTQ people, both as a symptom of their intersection with poverty and as connected to specific policies and practices carried out in the interest of capitalists and capital accumulation.

All of this is political work, and it is revolutionary work. Serving and supporting these more marginalized members of the 2S-LGBTQ community requires a different approach than one resting on a shared queer identity. Instead, it demands a focus on shared experiences and connected causes – one that sees queer and trans people as part of a class, with common material conditions. It requires a queer anti-capitalism. And it asserts the need for strategic partnerships outside of the state, between and among communities, with a common goal of the reinvention of society. In short, it must be radical – defined, as Angela Davis does, in the sense of grasping things at the root; speaking to the source rather than the symptoms. Without this focus, and given their increasing coordination with the state or the private sector, the activism of these organizations will eventually align with the aims and interests of their more privileged members.

So if we can recognize the inherent limitations of activism that takes place solely on the basis of a shared 2S-LGBTQ identity, who is doing the necessary anti-poverty work by and for marginalized 2S-LGBTQ folks? And when 2S-LGBTQ groups that ally with the state and corporations have the easiest time getting money, how do other organizations stay afloat?

What’s in a community?

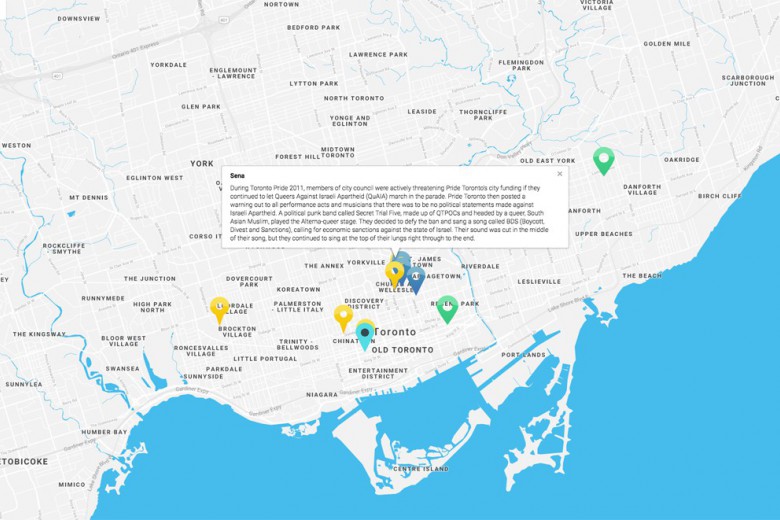

On January 23, 2019, the Toronto Life House of the Week was a $1.7 million property in Toronto’s Moss Park neighbourhood. The house is about a five-minute walk through Toronto’s rapidly gentrifying downtown east end from the John Innes Community Recreation Centre, the intended site of a massive development project headed by The 519, a local LGBTQ non-profit, with the goal of revitalizing the centre and improving its services.

Local opinion is divided on the John Innes Community Recreation Centre project. Though many Moss Park residents have told reporters that they welcome an updated facility, others are concerned that what was initially billed as a site “focusing on the LGBT sport community” would become a watering hole for the area’s wealthier residents while alienating the poor people – 2S-LGBTQ and otherwise – who live there. Absent from discussions of the site is commentary on the area’s worsening inequality, where a number of crisis service centres compete for space against condos with skyrocketing rents.

Activists argue that by viewing the “LGBT community” as a monolithic entity with an investment in a specific vision for the area, they are erasing the queer and trans people for whom poverty and gentrification are key issues.

For trans sex workers, for example, how might an influx of monied gay men bring more policing (and thereby harassment) into their lives? What will happen to homeless people, who rely on the park for spaces to sleep, during construction? How will the presence of security impact people of colour in that space?

In the wake of this shift, much of the vital work that keeps marginalized LGBTQ2S people alive is not done by explicitly “LGBTQ” organizations. Instead, it is done by queer and trans people like Monica Forrester, working in organizations that primarily serve sex workers, homeless people, low-income folks of colour, refugees, and incarcerated people.

Established and well-funded LGBTQ non-profits tend to focus more on issues of general LGBTQ education and legislative recognition rather than service provision or anti-poverty work (here, I deliberately exclude “2S,” recognizing that two-spirited activism is never truly undertaken or uplifted by organizations that collaborate with the colonial state). Mainstream LGBTQ organizing, with its emphasis on apologies, information, and police partnerships, assumes that the community has grown up and grown out of the extreme persecution and precarity that required its initial radicalism – “transcending basic issues of health, safety, economic security and social stability,” in the words of Colin Walmsley of the Huffington Post. In the wake of this shift, much of the vital work that keeps marginalized LGBTQ2S people alive is not done by explicitly “LGBTQ” organizations. Instead, it is done by queer and trans people like Monica Forrester, working in organizations that primarily serve sex workers, homeless people, low-income folks of colour, refugees, and incarcerated people.

Forrester is among the anti-poverty activists involved in organizing against Moss Park’s gentrification and has worked closely with The 519 as a consultant on trans-related initiatives. She is a program manager at Maggie’s: Toronto Sex Workers Action Project and also heads up the agency’s Indigenous programming. Maggie’s shares an office with the Prisoners with HIV/AIDS Support Action Network (PASAN).

“Maggie’s has always advocated for people who are most marginalized – not just within the LGBT community, but within all communities that have any sort of relation to sex work,” Forrester tells me over the phone. “A lot of our service users have multiple issues; for some of them, in their lives there may be homelessness, there may be drugs, street work, or conflicts with the law or with police.”

Maggie’s services far exceed the agency’s size. They have a staff of 16, run multiple weekly programs, conduct lobbying and training workshops, and directly intervene to protect and support their service users. When Alloura Wells went missing in 2017, for example, Forrester initiated searches, reached out to contacts, and informed other community organizations; she even helped secure funding for Wells’ family and funeral. Yet, for the most part, the agency’s funding is dependent on its ability to access specific and competitive grants and bursaries from the government – funding that is not guaranteed and represents only a fraction of the budgets of provincial or federal governments.

“Maggie’s has always advocated for people who are most marginalized – not just within the LGBT community, but within all communities that have any sort of relation to sex work.”

Forrester tells me about several experiences she’s had with organizations that ostensibly serve the 2S-LGBTQ community yet don’t recognize their own potential for improving services for more marginalized trans or queer community members – trans women, sex workers, homeless people, and low-income folks of colour, among others. As a result, they end up missing big opportunities to do good, despite having already secured funding that other agencies might desperately need. “Sometimes when you take money out of agencies that are really doing the work, it’s really problematic, because then these places are just kind of feeding into what they do to get more money within the agency. It can be a good thing, but it can be a bad thing,” she says.

Since Alloura Wells’ death, “now we have five trans women of colour groups happening, because an agency realizes ‘oh, we can get money for that,’” says Forrester. “How is that really playing out within the communities? How is that program looking for people that are actually homeless, or trans, or racialized, or sex workers?” she asks.

“What happens is usually that these agencies can get money, but it’s only for, like, a year. So they establish this program, and the program is successful, but then after a year they have no more programs. What does that mean for the service users?”

For other organizations, funding is even less secure. RaricaNow is an Edmonton-based agency that provides services for transgender immigrants and refugees of colour. They help trans newcomers navigate the asylum and immigration process, overcome isolation and language barriers, and access state services. As well, they advocate to stop deportations, contact health-care providers, and offer education and training for other community members who may be unsure of how best to meet the material and cultural needs of LGBTQ refugees and new immigrants. Yet they run almost entirely on donations and volunteer labour; most of their expenses are paid out of pocket, and much of their work is done pro bono to serve clientele who are among the most marginalized members of the wider 2S-LGBTQ community.

“Our work is pretty revolutionary. It is not being done in Canada or elsewhere, and it is led by trans refugees and trans people of colour.”

“At Rarica, we are a family,” says Adebayo Katiiti, the agency’s founder. As a transgender refugee himself, Katiiti understands that the services offered by RaricaNow are often a matter of life and death for their clients – in his words, “our work is pretty revolutionary. It is not being done in Canada or elsewhere, and it is led by trans refugees and trans people of colour.”

In 2018, RaricaNow joined several other members of Edmonton’s Black, Indigenous, and racialized 2S-LGBTQ community in requesting emergency financial assistance from the Edmonton Pride Festival. As Katiiti describes, they were met with hostility and diversion from the organization’s board of largely white, cisgender, and Canadian-born directors, who didn’t understand the stakes or consequences of RaricaNow’s work. The messy and months-long process of negotiating with the Edmonton Pride Festival culminated in the board of directors calling the police to escort RaricaNow organizers and other activists from a meeting.

According to Katiiti and his colleague V. Guzmán, who works with the racialized 2S-LGBTQ collective Shades of Colour, the money they requested from the Edmonton Pride Festival wasn’t simply a handout. They saw the Festival as the largest and most well-funded 2S-LGBTQ organization in Edmonton. They hoped that redirecting some of those funds would help improve the circumstances of non-white queer and trans people in a city where racism is a public fact.

Guzmán tells me that communication quickly broke down. The Edmonton Pride Festival is a non-profit corporation, meaning it has very strict rules about how it can and cannot use its funds. Getting around these barriers and identifying appropriate loopholes or partnership opportunities requires coordinated political will from within the organization. Put simply, if they don’t want to play ball, they won’t.

On another level, the funding and granting structure by which many community organizations run (including non-profits) limits their ability to divert money even as needed. According to the Edmonton Pride Festival’s 2018 annual report, only 11 per cent of their funding came from public coffers, while 61 per cent came from sponsorships. In most cases, private sponsors (many of them large banks, communications companies, and multinational corporations) indicate how their funds are to be used, earmarking them for specific events and marketing placements. This model also effectively reduces opportunities for larger organizations to pursue partnerships with more radical agencies.

Yet even when organizations are publicly funded, that money is rarely enough to fully cover costs – let alone to address the root of a social problem or sustainably improve the circumstances of those in crisis. According to Forrester, for example, funding for work at Maggie’s comes from the Ministry of Health, the Toronto Urban Health Fund, and the Public Health Agency of Canada. As well, the agency has specific funds set up in the name of Alloura Wells and Moka Dawkins, which go toward the community drop-in service and the legal fees for sex workers facing incarceration. Since 2016, the Public Health Agency of Canada has committed $26.4 million per year to community-based work on HIV-related issues; it sounds substantial, but that funding must be stretched between 123 organizations, which amounts to roughly $214,634 per organization if split evenly. In a city like Toronto, where office space is expensive even on a sliding scale, and for a program that would require at least one full-time facilitator and sufficient food, transportation, and materials for all participants, that’s barely enough money to run a workshop for a full year.

This piecemeal funding model also ensures that those working on the front lines are not able to earn a sustainable living through community work, and that organizations will increasingly look to private donors to cover costs.

Those with existing knowledge and a multi-talented team can stretch a dollar: PASAN and Maggie’s are both prolific and effective activist organizations by any measure. But as U.S. scholars Dean Spade and Hope Dector have pointed out, the competitive non-profit funding landscape often requires already marginalized activists to accept low payment for their labour and appeal to powerful institutions with little knowledge of their specific circumstances. Though it makes sense that those impacted by these issues be the ones entrusted to carry out relevant programming, this piecemeal funding model also ensures that those working on the front lines are not able to earn a sustainable living through community work, and that organizations will increasingly look to private donors to cover costs – a trend noticeable in the annual report of any LGBTQ non-profit like Egale or The 519. In short, it’s a mixed bag, and as Forrester argues, the ones who pay the price for these shortfalls are usually the service users.

In other cases, community organizations turn to fundraising to fill the gaps, especially if they are too small or new to be eligible for public grants. For example, Katiiti tells me that RaricaNow relies on fundraising to make ends meet.

Another option, practised in rarer cases, is turning a for-profit enterprise into a worker-owned one – Halifax coffee shop Glitter Bean did just that last year, when its queer and trans staff pooled their resources and coordinated with a local union to take over ownership of the shop after their employer allegedly refused to pay them fairly. While this isn’t a case of activist organizing per se, it does demonstrate the capacity of 2S-LGBTQ people to succeed when they organize together as workers and look out for their combined interests in coalition with other strategic partners. Recognizing the power of labour and collective action to address the most pressing issues for the most marginalized within our communities reveals just how much can be done when 2S-LGBTQ people work together as a class.

Cozying up to the state

The public funding that goes to organizations like Maggie’s, PASAN, The 519, and Egale creates both opportunities and constraints. On one hand, this capital enables agencies to carry out projects that will directly improve the lives of service users and community members, projects that the agencies can run and refine on their own terms and according to their own experience. On the other hand, this reliance on government grants and bursaries also comes with conditions. It necessarily erodes their capacity to develop parallel institutions – to provide services and resources outside of the state that exist by and for the communities themselves. Instead, by fostering closer relationships with the state, the agencies in question are required to accommodate and adapt to the needs of the state, rather than vice versa. Moreover, it prevents them from diverting funds to different causes as needed, or addressing the root of an issue rather than its symptoms.

Recognizing the power of labour and collective action to address the most pressing issues for the most marginalized within our communities reveals just how much can be done when 2S-LGBTQ people work together as a class.

“I live on Church Street [the heart of Toronto’s Gay Village], and I see a lot of queer youth that are homeless, sitting in front of stores. We have a few agencies on Church Street – why aren’t they doing outreach to those people? Why are we just walking past those people?” asks Forrester. Our interview is coming to a close, and I can hear the urgency in her voice. “These things aren’t gonna get any better. It’s gonna get worse. We live in a city that is expensive, where housing is next to nil unless you make over $4,000 a month. We need to really address that all community members matter. Until we address all these different things, things are just gonna stay the same.”

The author has chosen to use 2S-LGBTQ rather than Briarpatch’s house style of LGBTQ2S, in order to to foreground the unique experiences of Indigenous people and to indicate that two-spirited people stand outside of a colonial gender and sexuality framework.