In front of the old Second Cup on Church Street, you could find the Steps. There, many of Tkaronto’s young queer and trans Black, Indigenous, and people of colour (QTBIPOC) gathered.

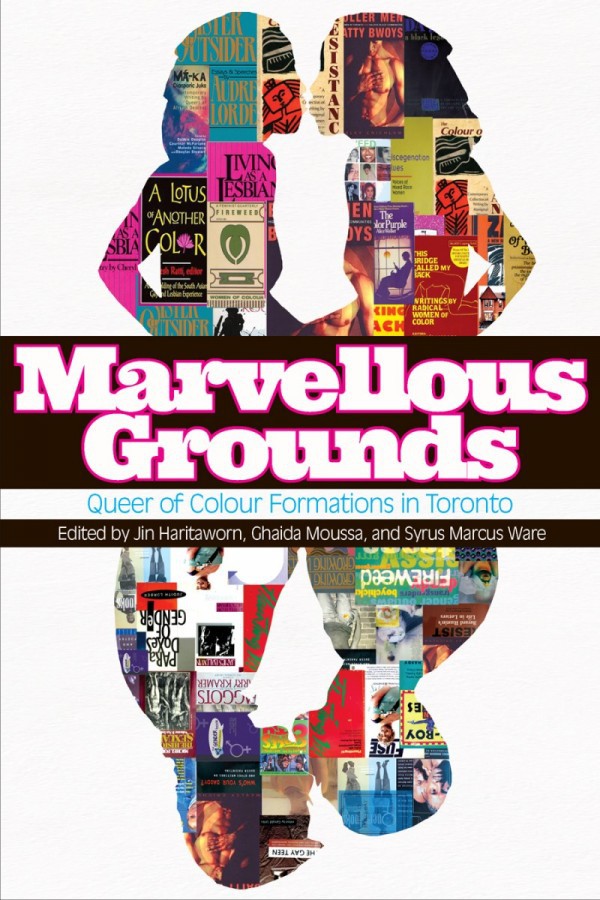

“The Steps were meaningful precisely because they existed without an imposed meaning. They functioned in the way they did because of who was using them,” writes Asam Ahmad, in his essay “Queer Circuits of Belonging.” At the time, city planners and politicians were biting off chunks of the Gay Village, chewing them up and spitting them out sanitized. In 2005, the Steps were demolished – they were one of the final holdouts against the gentrification that would reserve the Village for its “neoliberal white gay consumer citizens,” write the editors of Marvellous Grounds.

It is summer 2013. I am 21 going on lesbian lola, never having heard of the Steps. I am a Scarborough-born filipinx femme, glitter ready to gleam with the melanin queers of Tkaronto. I have discovered QTBIPOC scenes, but what I really seek is queer community and ancestors who share commitment to long-term, intergenerational care.

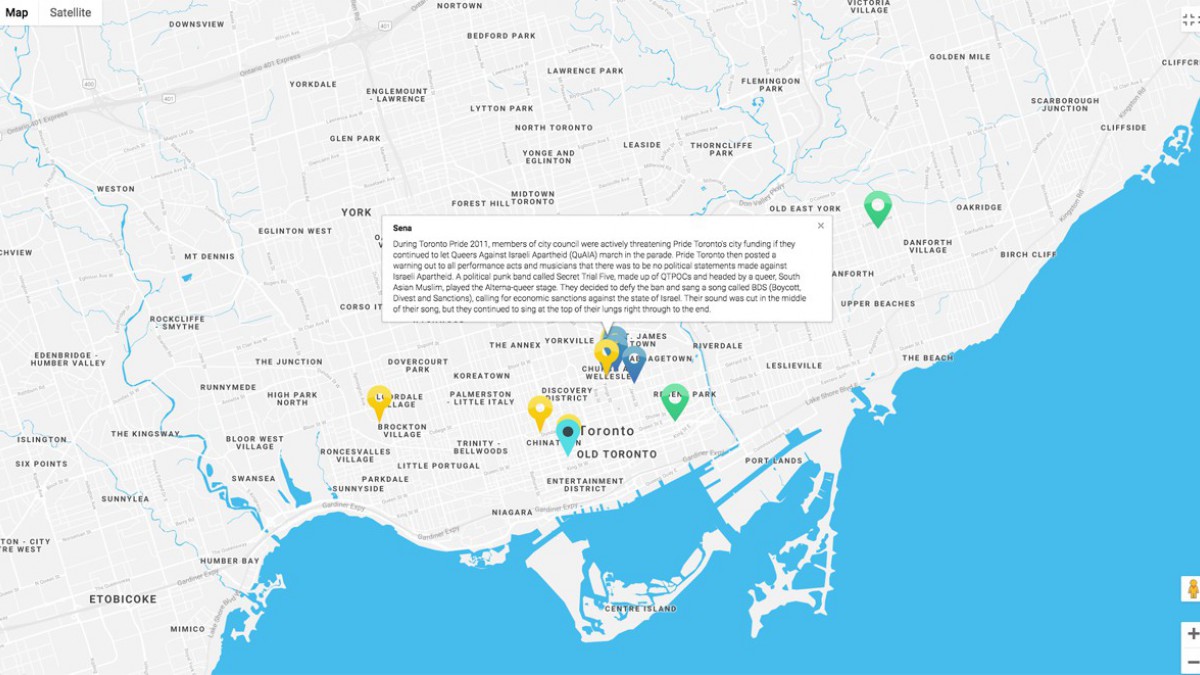

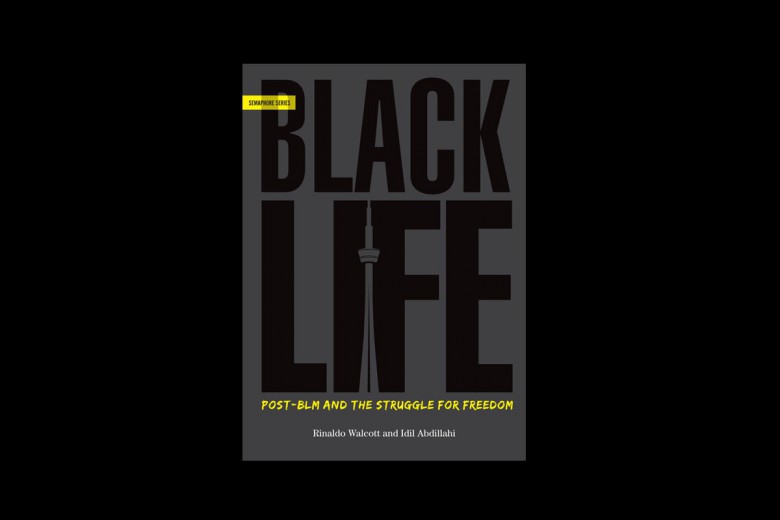

Marvellous Grounds is a map of queer and trans ancestry and freedom-making in Tkaronto that I would have loved to access back then. The book covers over four decades of QTBIPOC history in personal essays, interviews, research articles, and poetry organized into three key themes: counter-archives, cartographies of violence, and community healing. Authors offer snapshots of QTBIPOC movements, like those of trans women of colour and sex worker activism in the ‘80s and ‘90s; glimpses of revolutionary creative projects such as Colour Me DRAGG, a QTBIPOC cabaret-style showcase that ran from 2006 to 2011; they also pay homage to spaces such as Unit 2, a DIT (do-it-together) community hub for artists, performers, and facilitators. Alongside the book, Marvellous Grounds has a web-based component that allows users to mark their moments of QTBIPOC joy, grief, rage, and connection on an online map of the city.

Marvellous Grounds gifts readers with a rich archive of QTBIPOC stories of struggle, conflict, kinship, and care-making – offering a meaningful alternative to the “curatorial approach that ‘collects’ QTBIPOC objects and subjects for an ever more colourful archive whose foundations remain firmly white,” as the editors explain in their introduction.

What I really seek is queer community and ancestors who share commitment to long-term, intergenerational care.

Through the experiences of contributors such as Ahmad, who reflects on homelessness in Tkaronto in the process of navigating queer kinship and mentorship, we are reminded that while many QTBIPOC are invested in freedom-making, our bodies are often still dancing sites between choice and circumstance. Shaunga Tagore similarly reflects on the interplay between agency and inheritance in “A Love Letter to These Marvellous Grounds.” She professes, “I do not need to hold this trauma in my body in order to honour who gave it to me.” Her essay celebrates QTBIPOC bodies as placeholders of memory, where healing can occur not only through preservation, but also through movement. It reminds me of Palestinian filmmaker Nasrin Himada’s explanation, at a show this spring near Lansdowne, that nostalgia can be kinesthetic, transmuting memory into movement.

When I agreed to review Marvellous Grounds, I didn’t realize that I knew any of the contributors except Jin Haritaworn, one of the three editors. I met Jin at the Cutie.BPoC Festival in Berlin in 2015, where they were co-guiding a discussion on community care. Once I opened the book, I realized I’d met 15 of the contributors, all in the context of BIPOC community work in different parts of the world. For me, this is evidence of Tkaronto as a rich translocal hub for QTBIPOC community work.

As such, Marvellous Grounds is romantic, without romanticizing the struggle.

Amid all this richness, one thing deserves more focus in Marvellous Grounds: Tkaronto’s Indigenous her-stories. The editors note in the introduction that “it is impossible […] to read the current archive without investigating, in its creases, whose work has been pillaged, whose land has been stolen, who has been lost or left behind, murdered or displaced, erased or deemed disposable.” In a compilation so intimately place-based, there certainly could have been more space dedicated to the legacies and presence of two-spirited and Indigenous folks more broadly in Tkaronto, and to unpacking how anti-Indigeneity, settler colonialism, and Indigenous erasure exists within QTPOC communities.

More than simply a static archive, Marvellous Grounds is a call for QTBIPOC to step into a “permanent readiness for the marvellous,” a phrase the book borrows from Martinique-born scholar and activist Suzanne Césaire’s description of surrealism. This archive marvels not only at the love, generosity, and care between QTBIPOC folks of Tkaronto, but also on communal tears shed for lives lost at the hands of structural violence. As such, Marvellous Grounds is romantic, without romanticizing the struggle.