It was the most unusual town hall Toronto had seen in years. Even after the venue was moved to a 498-seat theatre to accommodate demand, registration filled up almost a week in advance and the rush lineup stretched around the corner. Yes, a rush lineup. For a community town hall. At the first Sidewalk Toronto Community Town Hall on November 1, 2017, the municipal was sexy again.

Inside, a veritable who’s who of Toronto’s urbanist, policy wonk, political, innovation, tech, and start-up scenes milled about. There was a hum of excitement as everyone prepared to hear about Sidewalk Labs’ vision for “the neighbourhood of the future.” And outside the glass walls of the St. Lawrence Centre for the Arts, activists from Toronto ACORN (Association of Community Organizations for Reform Now, a national organization of low- and moderate-income families) chanted slogans in support of affordable housing.

From the very beginning, Sidewalk Labs’ venture has been marked by protest. The project to build a so-called “smart city” on Toronto’s eastern waterfront has attracted considerable controversy and criticism since it was announced during a 2017 press conference featuring the prime minister, Justin Trudeau, and Eric Schmidt, the chairman of Sidewalk’s parent company, Alphabet. The project to be built at Quayside, a 12-acre slice of mostly undeveloped land, is unprecedented in its vision. Never before have so many elements of urban techno-utopia been assembled together in quite this fashion, at least in North America: self-driving vehicles, underground waste-disposal robots, “dynamic streets” with road markings that change depending on the time of the day, digital electricity systems. Given that Sidewalk Labs is a sister company to Google, the first set of concerns centred around data, privacy, and surveillance. Over the last year and a half, as the process has unfolded, a far more familiar yet even more complex set of concerns has emerged: governance, privatization, and gentrification.

The primary innovation in this project hasn’t been a smart device that improves the quality of urban life; it’s been the private-public-private partnership between Sidewalk Labs and Waterfront Toronto, itself a quasi-public corporation with limited accountability. The agreement, first signed in October 2017 and updated in July 2018, converts the role of Sidewalk from vendor to partner, with a wide-ranging mandate for issues such as economic development, housing affordability, environmental sustainability, and – perhaps most dangerously – privacy and data governance. In effect, this means that Sidewalk is helping develop the policies to which it is itself subject. This goes beyond a mere conflict of interest to a case of regulatory capture, where a private actor amasses considerable influence in directing the nature and function of regulations that should only be established through a public and democratically accountable process.

Over the last year and a half, as the process has unfolded, a far more familiar yet even more complex set of concerns has emerged: governance, privatization, and gentrification.

Sidewalk is also investing $50 million into this process, helping pay for Waterfront staff working on the file. This murky relationship between Sidewalk and Waterfront means that Sidewalk has a share in the intellectual property that will be developed through this project, and it is able to use Toronto as a testing ground for products and services that it will eventually market around the world. It means that Sidewalk has been able to drive the narrative about this project from the beginning. It means that Toronto’s residents get to see a new chapter of urban entrepreneurialism unfolding as the stewards of its waterfront welcome corporate capital under the guise of innovation.

This sleight of hand has not been missed by Torontonians who pay attention to such issues – it has been subject to vociferous critique and questioning by a slew of local residents and community groups who have pushed politicians and journalists to pay attention. In February, this resistance, led by open government advocate Bianca Wylie, materialized in the form of #BlockSidewalk, a group calling for a shutdown of the Quayside development project (I have been supporting the campaign from its inception). The project has also received significant international attention from urbanists, policy-makers, and academics around the world, becoming a crucible for concerns about smart cities and the potential for technology to become a Trojan Horse for privatization.

Indeed, the story of Quayside is only the latest chapter in a series of struggles between communities and Big Tech that are emerging in cities around the world. At the turn of the year, community groups in New York City, particularly Queens, rallied to fight against Amazon’s much-vaunted new corporate headquarters, HQ2, that was to be built in Long Island City, emerging victorious. In Berlin, locals successfully protested a new Google Campus start-up hub in the Kreuzberg district, forcing the company to give the space to two non-profits. This is to say nothing of the past five years of regulators’, tenants’, and workers’ struggles against the deeply pernicious effects of ride-sharing, short-term rentals, and the so-called gig economy. The battle against Big Tech has now decisively emerged as a new front in the fight for the right to the city.

Communities and corporations have been battling for generations, but this new round is remarkable because of both the nature of the corporate actors and their ambitions. Whereas urban activists have previously mostly contended with well-established actors like real estate developers or big-box supermarkets, now they face relatively young Silicon Valley technology giants: Google, Amazon, Airbnb, Uber, and more. These are companies defined more by their valuations than by their actual wealth; they are notable more for their intangible than tangible assets; and they are dominant in digital arenas first, physical arenas second. Their most loyal clients tend to be liberal-leaning urbanites under 35 who grew up with technology seamlessly stitched into their everyday lives.

The battle against Big Tech has now decisively emerged as a new front in the fight for the right to the city.

These tech giants are now encroaching on the streets in very tangible, but fairly diverse, ways. Uber and Lyft have undercut taxi industry regulations and driven people away from public transit; Airbnb has advanced gentrification by crowding out long-term rentals in squeezed housing markets; Amazon upended the economic development paradigm when it launched an auction for cities to compete to host its next headquarters; Sidewalk Labs wants to disrupt the neighbourhood itself.

This disruption looks like a deeper form of quantified technocratic governance, enabled by Big Data. By installing sensors across the urban environment, as well as by tapping into existing unprotected sources such as mobile phones, both public and private entities are able to collect and analyze unprecedented amounts of data. Beyond the privacy issues that this opens up, there is a broader concern about governments making decisions solely on the basis of statistics. As Lorraine Chuen writes in GUTS Magazine, data and statistics have long been used in urban planning for policing and surveillance of racialized people in Canada. Indeed, the Toronto police have already been using facial recognition technology for surveillance and profiling for over a year. And in 2018, Toronto police proposed the “ShotSpotter” system, which would install microphones around the city to detect the locations of gunshots. The Canadian Civil Liberties Association responded that “if placed in poor or diverse neighbourhoods, the new technology may be an unconstitutional sucker punch to racialized communities of Toronto.” The technology was eventually scrapped over concerns that it may violate Charter rights, as well as the simple fact that it doesn’t work.

Sidewalk Labs has already produced and implemented its own surveillance mechanisms, in the form of free Wi-Fi kiosks in New York City and London that feature cameras and microphones. Its current efforts in Toronto seem to be even more expansive, carrying out research and development so that it can become the market leader for managing information flows and deploying technologies, if not outright controlling the “digital layer” for cities.

Residents have been concerned about Sidewalk’s plans ever since the partnership with Waterfront Toronto was announced. They asked about the kind of data that Google expected to collect, the technologies it would use, and the privacy policies that residents could expect. They asked about the governance of the project and the business model, worried about the extraction and monetization of personal data.

Sidewalk initially promised openness, releasing a public engagement plan in February 2018 touting collaboration and co-creation to “imagine this new neighbourhood together.” Despite an impressive array of activities that included public roundtables, design jams, neighbourhood meetings, and a physical showcase for urban living technologies at its headquarters on 307 Lake Shore Boulevard East, however, it provided only carefully crafted messages and vague responses to questions. The company repeatedly told residents that the details were being worked out and that they should wait for the plan. As housing activist and #BlockSidewalk member Melissa Goldstein explains, “Sidewalk hasn’t presented anything concrete. How do you oppose that?”

Meanwhile, Sidewalk pushed forward its own agenda; instead of addressing data governance, it talked about parks and public spaces. When it did share proposals, it preferred to present already-fleshed-out ideas with little room for debate, leaving conversations with residents to be a largely performative exercise. A former Sidewalk Toronto employee, who asked that their name remain private, tells me this was intentional, and explains that facilitators at the 307 offices had expressed their frustration to senior management but were told to stonewall questioners.

As a result, Sidewalk’s “engagement” has felt one-sided and inauthentic to many residents, ranging somewhere between placation to outright manipulation in Sherry Arnstein’s classic ladder formulation of citizen engagement. In addition, and contrary to what was agreed upon, Sidewalk Labs has led most of the public engagement so far, with Waterfront Toronto often anonymous or muted.

“Sidewalk hasn’t presented anything concrete. How do you oppose that?”

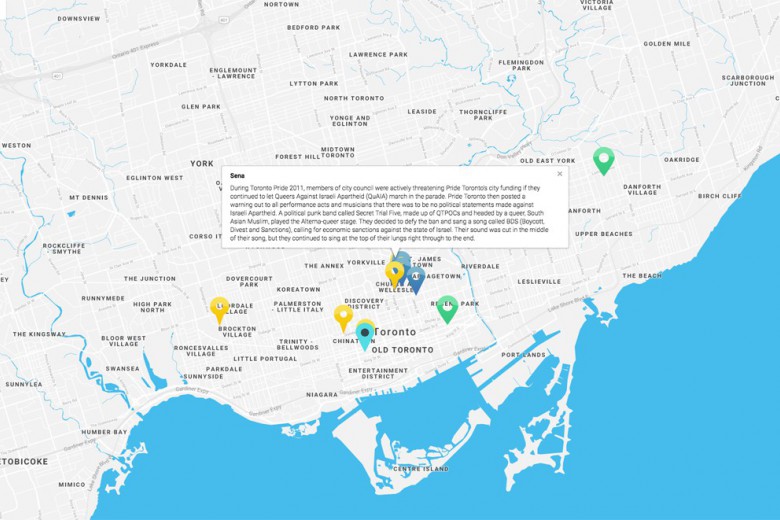

Take the example of CommonSpace. In October 2018, Sidewalk proposed the creation of a “civic data trust,” an independent entity charged with data stewardship. When it presented this proposal to Waterfront (featuring a Freudian slip about the role of the private sector in developing public policy), Sidewalk insisted that this was only a proposal and it wouldn’t actually carry out any data collection or test any technologies on Torontonians without sharing those plans in advance. Yet less than two months later, it was revealed that Sidewalk had in fact both developed as well as prototyped an app called CommonSpace, which collected data on people who visited R.V. Burgess Park in the Thorncliffe Park neighbourhood, where most residents tend to be Black and brown new immigrants. Sidewalk had worked with two local non-profits and had collected and analyzed data on Torontonians in violation of its own proposed protocols.

This dance has played out over and over since October 2017; as a result, an increasing number of actors have lost their patience with Sidewalk and, more significantly, Waterfront Toronto, ostensibly the protector of the public interest in this project. Julie Di Lorenzo, a real estate developer, resigned from Waterfront’s board due to concerns about Waterfront Toronto’s independence in July 2018, the day before the new “Plan Development Agreement” was signed; Saadia Muzaffar, of Waterfront’s Digital Strategy Advisory Panel, quit in October when she felt the organization was not taking concerns seriously, and joined #BlockSidewalk. Ann Cavoukian, Ontario’s former Information and Privacy Commissioner who had been working as an advisor to Sidewalk Labs, also quit in October when Sidewalk Labs refused to follow her recommendations to protect privacy. In December, Ontario’s Auditor General released a scathing report on Waterfront Toronto’s process of awarding the contract to Sidewalk and the mandate of the project, after which the Ontario government fired three board members from Waterfront, including the chair and the interim CEO. More recently, in April, the Canadian Civil Liberties Association launched a lawsuit against Waterfront and all levels of government, challenging the agreement between Waterfront and Sidewalk.

While governing bodies try to get their bearings in a regulatory environment where data, technology, privacy, and intellectual property policies are still open questions, and while residents are distracted by shiny demos, Sidewalk has been moving forward with its own plans. It has been engaging in a whirlwind of lobbying, with dozens of lobbyists registered at all levels of government – in April it was named the most active lobbyist in Toronto by a distance. Sidewalk’s delay in presenting the plan for Quayside has worked to its advantage, buying the corporation time to increase its influence. In an especially naked move, Sidewalk hired former city councillor Mary-Margaret McMahon as its “director of community,” presumably also putting up a “conflict of interest” sign on April Fool’s Day.

These events reveal a pattern of Sidewalk weaponizing ambiguity, playing divide-and-conquer, and co-opting critique, mirroring the strategies used by other tech giants such as Uber and Airbnb. Their strategic foundation places a heavy emphasis on marketing and direct-to-consumer public relations, relying on the halo of innovation and progress that the tech industry has long worn. As scholar Molly Sauter has described, Sidewalk’s charming, playful images of the future, released on a regular basis and republished with nary a critical eye by news editors across the country, function as “materials of persuasion, not collaboration.”

Sidewalk’s charming, playful images of the future, released on a regular basis and republished with nary a critical eye by news editors across the country, function as “materials of persuasion, not collaboration.”

These images have been accompanied by progressive language borrowed from revered urbanists like Jane Jacobs and Jan Gehl at every turn: “streets for people,” “human-centred design,” “public realm,” “neighbourhood well-being,” “social infrastructure,” “inclusive economic development.” Early on, Sidewalk emphasized its plan to build with “tall timber” – making load-bearing structures out of wood, not steel – while minimizing Replica, its tool to harvest location data from cellphones. This reflects a conscious effort by the company to shift the focus away from technology and bolster its credentials as a city-building force, not the sister company to Silicon Valley giant Google. To urban geographer Thorben Wieditz, who is part of the #BlockSidewalk campaign, this is deeply ironic. “Jane Jacobs was a critic of modern rational comprehensive planning techniques. If you think about what [Sidewalk Labs] is proposing, using big data, it is putting those people Jacobs was critiquing on steroids. We’re not engaging people anymore, we’re sitting on a computer and calculating sidewalk use.”

Relationships have been key. Since arriving in October 2017, Sidewalk has courted every imaginable demographic, using all of the earmarked $11.2 million budgeted for communications and a further $2.5 million budgeted for pilots “to familiarize Torontonians” – that is, press flesh across the city. There was the Sidewalk Toronto Fellows Program that took a dozen millennials on urbanist tours of cities like Amsterdam and Boston; the Residents Reference Panel with 36 participants engaging in regular meetings over nine months; six advisory working groups, each with about a dozen members; ten small grants to university faculty and graduate students in Ontario; and even a summer kids’ camp for children between the ages of 9 and 12.

Many of the Torontonians selected were not random; most members of the advisory working groups, for instance, represent celebrated urbanists and community builders from all walks of life, many of whom have remained silent as criticism of Sidewalk has grown across the city.

Wieditz also talks about how the financial clout of Alphabet has proven handy. “You’re not dealing with a rational opponent – they can lose millions of dollars if they want to.” By offering something to everyone, from construction jobs to affordable housing, “they can co-opt [dissent] in a way that traditional actors cannot,” he adds. “It takes a while for progressives to get a handle on these actors.”

It’s hard to shake the feeling that Toronto’s residents and institutions have been played. In return for engaging, Torontonians got their voices erased and literally minimized, with dissenting views dismissed as “minority reports” and placed in smaller font sizes in the report of the Resident Reference Panel. Waterfront Toronto, already struggling to fulfill its mandate, took a risk and has since found itself increasingly marginalized in its own smart city project as it struggles to be equal partners with the global technology juggernaut that is Alphabet.

All of this came to a head in February, when it was leaked that Sidewalk intended to develop a much larger chunk of land than the 12 acres of Quayside, and that it planned to recoup its investment in part by claiming a portion of the city’s property taxes. Not only did this galvanize a new round of community outrage and spark the interest of most Toronto city council members for the first time, but it also initiated the formation of #BlockSidewalk. With Toronto on a crash course with what the city manager called a “fiscal iceberg,” Sidewalk’s proposal to receive a cut of the city’s dwindling revenues in exchange for building a light rail transit line along the waterfront was a clear move toward privatization. “At the same time the city budget keeps shrinking, we’re inviting a trillion-dollar corporation to take over our land,” notes Wieditz.

“You’re not dealing with a rational opponent – they can lose millions of dollars if they want to.”

Over the past year, there have been a number of efforts to build public awareness of the project and coordinate the fragmented opposition that exists. Wylie has been tirelessly writing about the unfolding fiasco and helped launch groups like Tech Reset Canada and the Toronto Open Smart Cities Forum; a discussion on alternative urban futures organized by Nasma Ahmed of the Digital Justice Lab brought together community groups and academics to strategize about how Toronto could respond to smart city visions. While these efforts attracted limited attention from local media, they have mobilized dissatisfied Torontonians and paved the way for the creation of the #BlockSidewalk campaign, which provides a platform for residents to organize around, and has stated a clear goal: to shut down the project altogether.

#BlockSidewalk represents a break from traditional activism in the city. Its lead organizers, members, and supporters do not come from the left with a common language or a consensus on tactics. This isn’t a group of seasoned advocates with experience in political campaigns; this is a motley crew drawn from ordinary residents, technology workers, scholars, and policy analysts who are keenly aware of the threat of a wholly digitized public sphere. For a newly politicized group, questions of leadership and internal communication are as unresolved as grander questions of strategy and tactics. A few weeks after the campaign launched, Goldstein talked about the difficulties: “Everything was spur of the moment; we had no time to prepare before launching.”

The scope and issues at play also differ. The most successful urban campaigns tend to be local, grounded in neighbourhood-level issues like affordable housing and transit. In the case of Quayside, which doesn’t have any existing residents, organizers are confronted both with a new opponent and the lack of a natural constituency. “Nobody considers the Port Lands their neighbourhood. People aren’t personally invested in the outcome,” says Goldstein. Unsurprisingly, convincing existing organizations to join has been a significant challenge. As Ontario’s new Conservative government has battered the province with a series of cuts to social services and other government functions, most activists have been focused on protecting existing infrastructure.

While all organizing entails political education, #BlockSidewalk has the unenviable task of introducing and translating concepts such as public technology infrastructure and surveillance capitalism, and describing the dangers of handing private companies control over the “operating system” of the city. It has to focus the attention of Torontonians on the key issues, avoiding obfuscation and pushing back against the narrative that technology is inherently progressive. “It’s been difficult to convey how Sidewalk Labs may impact Torontonians and progressive space,” says Wieditz. Goldstein agrees: “It’s hard for people – unless they’re following the nitty-gritty – to understand what’s upsetting about this. To explain this is hard.”

“At the same time the city budget keeps shrinking, we’re inviting a trillion-dollar corporation to take over our land.”

Yet at the same time, #BlockSidewalk may point toward future directions for organizing, as the need to respond to Big Tech opens up both new questions and possibilities for progressive activists. There is the challenge of engaging existing communities on new issues, but also the opportunity of engaging new communities on some very old issues. For example, the question of how to challenge widely used service providers like Uber or Airbnb is the flip side of the question of how to build broad support for public transportation and residential housing stock while protecting the livelihoods of taxi drivers and hotel workers. The struggle over Quayside has also revealed fissures in the urbanist community in Toronto, a city that has experienced deepening exclusion, segregation and inequity in recent years. Presentations by prominent urbanists to the Toronto City Council in early June demonstrate strong differences in opinion regarding the Quayside project.

This is where unions, still the largest membership-based organizations in major North American cities, should play a more central role, says Wieditz. While local media focuses on data and privacy, Sidewalk Labs also creates issues that organized labour has traditionally pushed back against, like the privatization of future revenue sources, municipal services, and public land. These issues have powerful implications for workers and communities. As large collective actors, unions can help us to build the organizing capacity needed to deal with Big Tech and the questions it presents. There is huge potential in urban politics and community organizing for unions to matter outside of workplaces, for the labour movement to build density, and to renew itself.

In the case of Quayside, stopping Sidewalk’s smart city project could be the precursor to a larger conversation about the future of Toronto’s waterfront. Bringing together different groups that were formerly narrowly focused on their own issues – housing, transit, employment – to challenge a corporate utopia can lead to an exciting debate around what alternative urban futures look like.

For now, #BlockSidewalk is focused on lobbying Waterfront Toronto to cancel the project. “We’re not here to negotiate,” Wieditz tells me. “We have an uncompromising position against an irrational player: we want to send Google packing.”