Fatima was quick to find another townhouse for her family when her landlord – the multinational, multi-billion-dollar, Toronto-based Timbercreek Asset Management – issued eviction notices to dozens of families in the southeast Ottawa neighbourhood of Heron Gate in September 2015.

Fatima (which isn’t her real name) was living in one of the 83 townhouses that sat on a parcel of land that developers, speculators, city councillors, and urban planners were salivating over as the prime location for a new “resort-style apartment” complex. She and her neighbours were told they had until February 29, 2016, to leave. Aside from the trauma of displacement, the dead of winter is not the greatest time to be moving in Ottawa.

City parcel by city parcel, Timbercreek is evicting us and our neighbours, and demolishing family houses. Over 400 residents were served eviction notices this spring. In an interview with Muslim Link, Fatima, a member of the Heron Gate Tenant Coalition, described the pain of coming to realize Timbercreek’s ultimate goal of erasing Heron Gate.

“Losing my house was less important than my fear of losing my community.”

“Losing my house was less important than my fear of losing my community,” she says. “Timbercreek thinks because we are a majority immigrant community, they can take advantage of us, and because we are mainly low-income families that we do not know our rights – but they are wrong.”

Living with Fatima was her husband, their six children, and their granddaughter – nine people in a four-bedroom home. At the end of 2015, when she found another townhouse across the street in another parcel of the Timbercreek-owned property, she was denied the $1,500 promised to evicted tenants. Timbercreek told her she was disqualified because she found a place on her own, rather than through the proper “relocation process.” She fought back, but Timbercreek refused to give her the money.

Now, two and a half years later, Fatima and her family are being told for the second time they are being evicted, as Timbercreek now wants to demolish the houses on the parcel of land she moved to. They are being offered three months’ rent, as per Ontario’s Residential Tenancies Act, and $2,000 – though this time the money is being called a “moving incentive.”

“Timbercreek thinks because we are a majority immigrant community, they can take advantage of us, and because we are mainly low-income families that we do not know our rights – but they are wrong.”

But this round of evictions is different – tenants are organized across Heron Gate and we are ready to fight to save the neighbourhood. Fatima is standing alongside her neighbours to say, “WE ARE NOT MOVING.”

Video: Ikram Dahir has lived in Herongate for 27 years. Her family is facing eviction for the second time in two years.

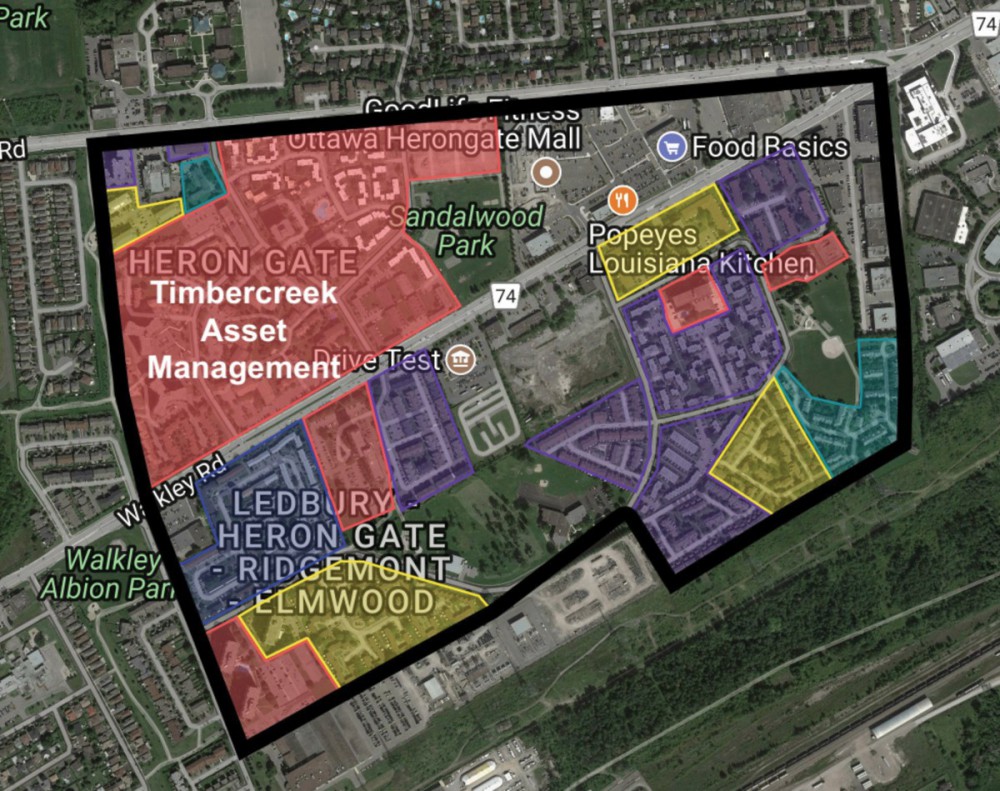

Mapping Heron gate

Timbercreek controls the housing of around 4,000 people in Heron Gate – one of the largest clusters of residential rentals owned by one landlord in Canada. The neighbourhood is split right down the middle into two wards, making collective organizing very difficult. The north side of Heron Gate – almost entirely owned by Timbercreek – has the highest level of core housing need in Ottawa. It is the neighbourhood with the most Brown and Black residents by far, and is one of the poorest. Structural inequality and racism are alive and well in Canada’s capital – and we are its prey.

Timbercreek’s Heron Gate is large enough to be its own census tract, so specific data is available on poverty, housing, and immigration through the 2016 Statistics Canada Census. One of the most significant tasks we undertook was a highly localized census of the 105 townhouses currently facing eviction. It turns out 44 per cent of the residents are of Somali descent, while 89 per cent of all residents are people of colour.

There are five and a half people per home, accounting for hundreds of children, and many of the households are led by single mothers.

These are working class families, and many of them are already struggling financially. But they have their community. Heron Gate is a phenomenally tight-knit neighbourhood, where doors are always open, where many members of racialized communities don’t feel like the “Other” and don’t have to live always braced for being told to “go back to your country.” The demolition of such a racialized community sends a larger implicit message: we don’t want you here.

Property record searches at the Ontario Land Registry office in Ottawa offered a lot more insight into the insidious ownership schemes behind this massive piece of real estate.

The demolition of such a racialized community sends a larger implicit message: we don’t want you here.

The properties in Heron Gate began to decline into squalor in 2007 when TransGlobe, one of the worst corporate slumlords in Canada, bought the properties from Minto, which began developing the land in the 1960s. TransGlobe was owned by Daniel Drimmer, who oversaw the financialization and commodification of housing by pooling capital from large investors and forming real estate investment trusts (REITs);

TransGlobe has since morphed into Starlight, Northview Apartment REIT, and a number of other monster landlords. There are YouTube videos from tenants and news articles dating from 2006 showing the neglect wrought almost overnight by TransGlobe on properties across Canada – roaches, mice, mould, leaks, foundation problems, broken and missing doors and windows, and more. Heron Gate appears to be part of a larger national campaign to slumify people’s homes, with the long-term goal of redeveloping neighbourhoods, turning housing into investment funds, and pushing working-class folk out.

Timbercreek has deliberately neglected Heron Gate homes for so long that, in the minds of most Ottawans, the neighbourhood has become synonymous with squalor. And they’ve been programmed to misunderstand the decay of homes in Heron Gate as the fault of the poor and Black and Brown residents – it’s chalked up to “laziness” or “cultural differences.” In reality, the neglect is the direct result of the racist, capitalist, and neocolonial structures of real estate and city planning that implicitly subject the poor to subhuman conditions while seeking high returns above all else. All our lives, we have seen the onus wrongfully placed on the families of Heron Gate – our families.

Timbercreek has deliberately neglected Heron Gate homes for so long that, in the minds of most Ottawans, the neighbourhood has become synonymous with squalor.

The responsibility to maintain livable conditions has always been and remains the landlord’s responsibility, set out in the provincial Residential Tenancies Act. However, through all the legal loopholes, the reciprocal back-scratching (Ottawa’s mayor and the local councillor received campaign donations= from Timbercreek in 2014, while the previous councillor is in business with a former vice-president of Minto), and the bureaucratic languor, this purposeful neglect is now the very thing being weapon-ized to displace over 400 people.

Eviction after eviction, parcel by parcel

Many tenants who are now organizing to save Heron Gate have known each other for years. Others only came on board in the past few months. But we all share a common struggle as we come from low-income families. We also know our neighbourhood inside out, so we’re miles ahead of any upper-crust Ottawa developers, let alone executives from Toronto.

The Heron Gate Tenant Coalition formed a few days after the current phase of evictions was announced on May 7, 2018. But preparations started months before, in fall 2017. Community dinners, public meetings, and walking tours were organized to start discussing housing affordability, displacement, and the power of the community to shape our neighbourhood. What emerged from this initial groundwork is the jaw-dropping insight that one company – Timbercreek – is monopolizing half our neighbourhood.

There are no tenant associations in Heron Gate. No social service provider was challenging these evictions in any capacity – we haven’t had any help from our community legal clinic or our community health centre. With the first wave of evictions in September 2015, tenants were left scrambling on their own. Many moved away, but some stayed in Heron Gate – which is why so many families are now facing a second eviction.

In reality, neglect is the direct result of the racist, capitalist, and neocolonial structures of real estate and city planning that implicitly subject the poor to subhuman conditions while seeking high returns above all else.

There was no precedent to follow in organizing to stop the evictions, so most of the tenants moved without a fight.

Many community support services have claimed “neutrality,” at best, in this fight, suggesting that tenants immediately look for homes and abandon their community. Tenants have the choice to stay and challenge the evictions or leave voluntarily. It has often felt as though the institutions entrusted with being an aid to the community have actually worked in service of the very people hurting the community. In comparison, the Parkdale Neighbourhood Legal Clinic actively helped tenants in Toronto fight above-guideline rent increases in 2017.

Unbeknownst to most people, Timbercreek has had a redevelopment plan for the area in place for years, which makes the continual shuffling of tenants from property to property that much more sinister. On May 7, 2018, tenants – many of whom have lived in the neighbourhood for decades, and others who are just finding their footing in the country as newcomers – were called to a meeting with Timbercreek and councillor Jean Cloutier. They were handed a cumbersome package, containing a plethora of documents explaining what was happening, and told they only had four months to leave their homes.

Imagine being a single mother of three or four kids, and having to figure out where to go in a city where the lack of affordable and suitable housing has been deemed a crisis. Imagine owning a private business, like a daycare, where all of your clientele is from the neighbourhood, and having to move, which would put you out of a job. Now factor in being the sole provider for your home.

The fight to stay in our neighbourhood has been a multi-generational effort. The elders have the social capital to reassure the younger, more timid, and vulnerable tenants that they do have the right to adequate housing. Tenants say that Timbercreek has tried to push them out by telling them that their locks will be changed and their belongings thrown out on the street if they do not voluntarily move by September 30. In turn, the youth in the community have done more of the physical work of canvassing, providing the community with daily updates, filling out work orders, and mobilizing on social media.

Social media has allowed us to connect with organizers and supporters from around the world. However, absolutely nothing can replace face-to-face interactions, tenant meetings, and personal connections with allies. Our most heartfelt work is in building relationships and opening space for sincere discussion on home turf – which gives us a leg up over developers, who use “community visioning” sessions as an opportunity to co-opt our desires and as a convenient public relations prelude to evictions.

It has often felt as though the institutions entrusted with being an aid to the community have actually worked in service of the very people hurting the community.

After putting a call out through our artist networks, Montreal-based photojournalist Neal Rockwell came on board to help us create our own videos and audio interviews, so we could control the message and encourage tenants to open up without the pressure of speaking to what is often (though not always) an insensitive, uninformed, and preoccupied mainstream media.

There is no one “best practice” in collective organizing – which is why making connections across cities and movements is so important, to learn as many skills and tactics as possible. From the Parkdale Organize! rent strike last summer and the East Hamilton rent strike this summer, to the 1970s battle for Milton-Parc, working-class people have come together to fight and win against plans by massive landlords and governments to raze our neighbourhoods. Drawing inspiration and strength from these struggles, we, too, are certain we will win.