It’s a warm September night, and tenants are piling onto the pavement behind the Citizen Action Committee of Verdun (CACV). The sound system is pumping music and someone’s firing up the grill. It feels like any other community barbecue, with people chatting over hot dogs and beers. But there’s a bigger reason everyone’s here tonight: Verdun is being swept by a wave of evictions and these tenants are fighting back.

“Verdun’s hit hard by the housing crisis,” says Lyn O’Donnell, a community organizer and intervention worker at the CACV. By the CACV’s estimates, the Montreal borough has lost over 2,500 low-income households in the past five years. “Evictions were never good, but before, at least you could theoretically find another apartment,” O’Donnell says. “Now, you get kicked out and you are totally screwed.”

It’s the same story across the province. In the past five years, rents have been rising at breakneck speed, giving landlords the incentive to kick long-time tenants to the curb. According to the Regroupement des comités logement et associations de locataires du Québec (RCLALQ), forced evictions more than doubled in 2023 alone. All levels of government could do more, O’Donnell says, but instead “they just throw the ball to each other, blaming each other.”

The Quebec government has proven itself hostile to tenants’ interests, backtracking not just on tenants’ rights but also on social housing.

Enter Bill 31, the Coalition Avenir Québec (CAQ)’s new response to the housing crisis. Passed in February 2024, the bill aims to “re-establish balance between renters and landlords and increase housing supply,” according to Housing Minister France-Élaine Duranceau. To say it’s been unpopular would be an understatement. Quebec’s tenant movement has fought hard against the bill since it was introduced last June, circulating petitions and holding frequent protests and occupations.

The bill has some provisions for renters: procedural changes at Quebec’s housing tribunal relating to evictions, as well as new compensation and damages for eviction. But those gains come at a steep cost: the end of Quebecers’ right to transfer their leases. It’s this, more than anything, that has renters in the province up in arms. Lease transfers aren’t just an early exit from your living situation. Absent proper rent controls, they’re a last-ditch tool to keep landlords from hiking rents between tenants.

“We’re talking about the first removal of rights from tenants in over 45 years – probably ever in the history of tenants’ rights in Quebec,” RCLALQ spokesman Cédric Dussault says. But this battle is about more than just lease transfers. Organizers say the CAQ has proven itself hostile to tenants’ interests, backtracking not just on tenants’ rights but also on social housing. Now Quebec’s tenant movement is faced with a new struggle: how to change course and find momentum in defeat.

“The devil is in the details”

It’s early December, and a couple hundred people have gathered in Montreal’s Parc-Extension neighbourhood for one of the last big protests against Bill 31. There’s a familiar face from September’s barbecue among the crowd: Nicholas Harvest, an organizer at the Regroupement Information Logement (RIL), a non-profit tenants organization in the city’s Pointe-Saint-Charles borough.

Harvest places low-income tenants into social housing in Pointe-Saint-Charles, but there’s always more demand than supply: “I have a list at work of [around] 1,200 people that are waiting,” he says, as the protest snakes its way through the streets. The Point, along with the two other neighbourhoods that make up the Sud-Ouest borough, have over 14 per cent of Montreal’s social and community housing stock, more than any other Montreal borough. “We’re noticing that people from across Montreal are coming to the Point to find low-income housing, because we have it.”

It’s thanks to a strong tenant movement that the Point has the social housing it does. In the 1970s, through groups like Loge-Peuple, the community mobilized to buy up and socialize residential units, but it wasn’t until the creation of the RIL in the late 1970s that the Point’s social and co-op housing really took off. By the end of the century, the Point was home to thousands of units of social and community housing, according to a 1999 report co-authored by Quebec’s housing society (SHQ).

Legal protections for renters, government funding for local tenant committees, and the ability to represent renters collectively at the National Assembly were all won by a strong tenants movement.

Their housing stock and continued activism still give the Point an edge in the fight for social housing today. But getting projects off the ground isn’t easy. With vacancy rates in the city hitting 1.5 per cent in 2023, buying and converting residential units is difficult to pull off. The City of Montreal’s bylaw to add social and affordable housing to new builds has been an abject failure, with almost every developer choosing to pay a fine instead. If community groups put up enough of a fight, they can get the City to buy and donate old buildings, often non-residential ones. Still, it typically falls on the groups to do the work of converting the buildings into livable social housing. Without provincial funding, it can be tough to actually see these projects through.

It's been just over a year since the CAQ axed Quebec’s social housing fund, AccèsLogis. For the tenant movement, AccèsLogis was an imperfect program but a victory nonetheless. After the federal government stopped funding social housing in 1994, Quebec was one of the provinces to create a replacement, with a push from tenants’ groups like the Front d’action populaire en réaménagement urbain (FRAPRU).

When tenants’ groups speak about the current approach to social housing, it’s with immense worry. The CAQ’s replacement for AccèsLogis, the Programme d'habitation abordable Québec (PHAQ), helps facilitate the creation of not only “social” but also “affordable” housing. The difference is significant: social housing is administered by governments, nonprofits, or co-ops, whereas affordable housing is typically just discounted private market housing. Although private developers are largely not biting – they’ll create a mere 7 per cent of PHAQ-approved affordable units, according to recent data – critics say the PHAQ’s whole structure is built with them, and not community groups, in mind.

Much of Verdun's new market housing are "regular apartments, but they’re at luxury prices.”

Bill 31 takes things a step further. The bill allows the Société d’Habitation du Québec (SHQ) to isolate and sell off parcels of social housing land. The proceeds can subsidize more social housing, but are more likely meant to incentivize the market-based “affordable” units that the PHAQ has made their focus. (After all, “it’s not social housing that’s going to solve the housing crisis,” according to the housing minister.)

“The devil is in the details with this bill,” says Lyn O’Donnell in her offices at the CACV. Much of the community she works with in Verdun are holdouts from a pre-gentrification era. For them, any housing that’s tied to the market is affordable in name only. “We’re going to have a bunch of luxury homes,” she says, then stops. “They’re not really luxury homes. They’re just regular apartments, but they’re at luxury prices.”

Jean-Vincent Bergeron-Gaudin, a doctoral student researching the history of tenant activism in the province, says one of the strengths of Quebec’s tenant movement is the political legitimacy that it’s enjoyed since the 1970s. He argues the victories activists won then – legal protections for renters, government funding for local tenant committees, and the ability to represent renters collectively at the National Assembly – have supported tenants for decades.

“Evictions were never good, but before, at least you could theoretically find another apartment. Now, you get kicked out and you are totally screwed.”

For many years, explains Bergeron-Gaudin, you could find tenant rights’ groups meeting with the housing minister one day and occupying their office the next – an approach better known as “conflictual cooperation.” He says it’s exactly as it sounds: “we’ll cooperate, we’ll consult,” he explains, “but we’ll remain in conflict with the state.”

That system is changing. “10 meetings with landlords, none with community groups,” disruptors told a crowd who had gathered last fall to hear Duranceau speak at a business summit in Montreal’s east end.* A month later, the minister would receive a slap on the wrist from the ethics commissioner for favouring an old developer friend and former business partner in an “abusive” fashion.

The status quo, in which tenants fought but were at least heard and recognized by the government, has broken, Bergeron-Gaudin says. Bill 31 has made headlines for the end to lease transfers, the first major tenant’s right to be lost. For tenant organizers, the province’s changes to social housing show an equally worrying willingness to dismantle and defund the infrastructure supporting tenants writ large.

“We’re talking about the first removal of rights from tenants in over 45 years – probably ever in the history of tenants’ rights in Quebec."

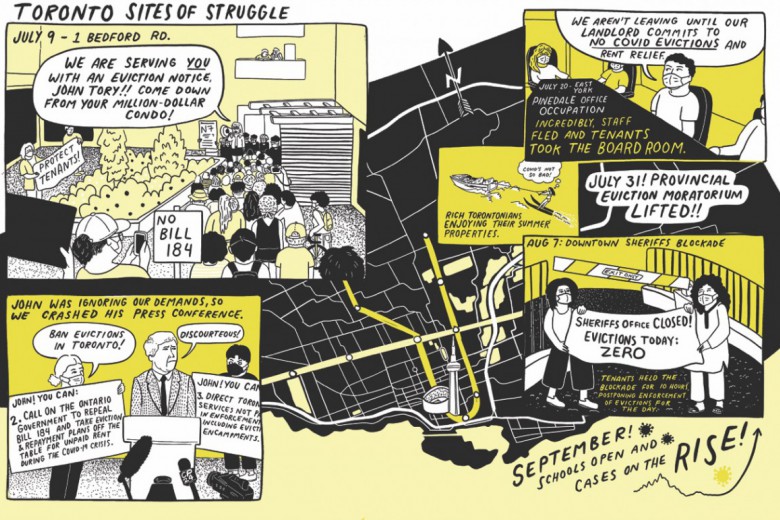

If that sounds dramatic, just look to Ontario to see what can happen under a hostile government. “The differences between Ontario and Quebec are pretty much decided by money,” says Geordie Dent, executive director of the Federation of Metro Tenants' Associations (FMTA). Dent says the province used to have more tenant organizations like the Federation of Ottawa-Carleton Tenants Associations, but that changed after Mike Harris became premier. “Harris came in and gutted all of that, and that’s why things went in different directions.”

Dent says that once government funding is gone, it’s often gone for good. Other levels of government or even foundations may fill in the gaps, like Toronto, where Dent says the municipal government steped up and saved the FMTA when the province cut funding. “Most often though, it just disappears,” Dent explains, and most people don’t even know what’s been lost. “If you talk to tenant groups, very few of them are calling for that money, because very few even remember that it exists.”

“The CAQ, François Legault, and Duranceau are creating a pressure cooker that they themselves cannot diffuse,” Harvest says, back at the protest in Parc Ex. But where will this pressure, this organizing capacity, be applied now that Bill 31 has passed? Dent’s words come to mind, a warning: “some people might hope it will go to a more radical type of organizing, but I think as everyone knows who studies politics, sometimes it doesn’t get funneled there. Sometimes it doesn’t get funneled anywhere.”

Taking back tenants’ rights

It’s a late November evening at the Cinémathèque québécoise, and Mathilde Capone’s Éviction has just premiered to a full house. Funny and intimate, the documentary chronicles the last days of a queer collective whose building on Rue Parthenais has just been sold. Now organizers and old members of the collective are taking the stage for an open mic.

There’s poetry in memory of old apartments, old neighbourhoods as they once were. There is, of course, gossip. “I will be spilling the tea,” promises our emcee, himself an old roommate at Parthenais. But first there’s a call to action, one that’s been present in some form at practically every housing-related event over the past six months.

Sofiane* has come to rally the audience against Bill 31 on behalf of the Front de Lutte pour un Immobilier Populaire (FLIP). An autonomous group, FLIP came together soon after the bill was introduced, and has undertaken much of the direct action against it. The group operates at different scales: disruptions of the housing minister by core organizers, open-invite demonstrations every week, and a few big street protests – the first of which was one of “the largest protest for the right to housing in Quebec’s history,” he tells the audience.

“What does it take to build communities and neighbourhoods that are ready and united to defend themselves when these things happen? It takes tenant organizing everywhere, in every neighbourhood.”

Tonight, it’s another protest that Sofiane is here to promote. Before he does, though, he talks about the film to explain why the FLIP was started. “There’s a moment when Marine,” one of the roommates in Éviction, “says it’s hard to organize as tenants, to have a tenant movement, because we’re so often isolated.” It’s not just the bill, but the isolation tenants face, that the FLIP is trying to overcome in their organizing.

Pierre*, also at the open mic, has seen firsthand what tenants can do when they act together. Formerly a volunteer at a nonprofit fighting houselessness, Pierre was unsatisfied with the scope of what she was able to achieve there. Now, she works with the fledgling Montreal Autonomous Tenants’ Union (MATU). Founded in Milton-Parc, where tenants’ fights in the 1970s won them the largest co-operative housing park on the continent, MATU is introducing a new generation of Montreal tenants to collective action against a housing crisis.

Organizers like Pierre work with interested tenants directly, giving them the tools and the training to form tenant councils in their buildings. A council might come about in response to an existing issue, but once formed, can act to prevent abusive rent increases and evictions – “so we’re not always on the defensive in these emergency situations where we don't have much power,” Pierre says.

Last summer, MATU tried a different tactic, putting out the call for a city-wide rent strike against Bill 31. If they got 5,000 tenants to sign on, the signatories would all refuse to pay rent until the bill was scrapped. In the end, only about 200 committed, and the strike was called off. It was always an audacious campaign, asking people to put their necks on the line for something bigger than a personal, immediate threat.

In the summer of 2023, the Montreal Autonomous Tenants' Union called for a rent strike in protest of the government axing tenants' right to lease transfer. 200 tenants pledged to strike.

Even so, Bill 31 has galvanized the public to act, Pierre says. “Bill 31 has mobilized a lot of people – it makes people responsive to [MATU]’s approach. A lot of people are thinking, maybe it does make a difference being together.” Even the rent strike campaign, though a failure on the face of it, locked in 200 tenants willing to organize with their neighbours, strike or no strike.

Soon after dropping this banner, this wall of the tenant's apartment was fixed.

You can see that in the crowd at the open mic. The community around the Parthenais collective includes tenant organizers and community workers, queer artists and performers, neighbours and friends. If Êviction seems to ask, “what do you do when you lose your home?,” their answer is clear: you come together and you organize.

On a rainy Friday evening in November, the Tenant Power Choir sets up in front of the offices of the Cucurulls, a landlord with a reputation for bad-faith evictions.

“What does it take to build communities and neighbourhoods that are ready and united to defend themselves when these things happen?” Pierre asks the crowd at the open mic. “It takes organizing. It takes tenant organizing everywhere, in every neighbourhood. That can be door to door, that can be tenants’ meetings, that can be flyering. Make a group chat, host a block party, meet your neighbours and learn about their problems. That way when things happen” – whether an unjust eviction or a chance to take back tenants’ rights – “you’re already united.”

It can feel bleak to stare down the loss of a right, as Quebec tenants are, but “the worst thing that we can do right now is to be pessimistic and to be defeatist,” says Nicholas Harvest, in the middle of the Parc Ex crowd. It’s a cold Saturday morning, and still hundreds of protestors have come out to make their voices heard. As Harvest speaks, in the background, a megaphone calls out a familiar chant.

“Tenants’ rights under attack – what do we do?”

“Stand up, fight back!”

*Pierre and Sofiane have requested to use pseudonyms for privacy and safety reasons. Pierre, Sofiane, and Bergeron-Gaudin’s quotes have been translated from French by the author.