“I was one of those people who fell through the cracks,” J.D. tells me.

J.D. grew up in Cape Breton, Nova Scotia. He came out as a trans man in his early 20s. At the time, there was only one endocrinologist – a doctor specializing in hormones – in the province who worked with trans patients. She worked part-time, and the waiting list to see her was between 18 and 24 months.

After he finally got the referral, J.D. spent several months being bounced from doctor to doctor. His files were lost, his appointments weren’t booked. These are the kind of clerical errors that seem to happen an awful lot to trans people, because endless referrals mean endless opportunities for human error and casual transphobia to collide.

In the meantime, J.D. tried everything he could to fill in the gaps. He researched testosterone-rich foods and changed his diet. He started exercising to redistribute his body mass into a more recognizably “masculine” shape. In 2012, a year after he got his referral, J.D. finally had a prescription for testosterone.

These are the kind of clerical errors that seem to happen an awful lot to trans people.

J.D.’s initial testosterone prescription was an unreasonably low dosage of 0.25 mg administered every week and a half. But increasing it involved another round of blood tests, and because his doctor didn’t set the customary checkup appointment, the endocrinologist’s office considered J.D. out of their system. Neither he nor his pharmacists nor his family doctors could seem to get anyone at the office on the phone. If he wanted to get proper gender-affirming medication, he would have to restart the entire process all over again.

“I got tired of the waiting. I got tired of not receiving care that was either culturally competent or medically adequate,” says J.D. “So I took matters into my own hands. I started self-medicating.”

Using this first prescription to gain access to testosterone, J.D. began gradually upping his intake. He’s been self-medicating with testosterone ever since.

On paper, Nova Scotia uses a model of informed consent, where family doctors are able to prescribe hormones or other gender-affirming medications to transgender patients, provided that patients have realistic expectations around results and risks. This is similar to the practice in Ontario and other provinces – in theory, it allows trans patients to open up to their doctors, access information, follow up with blood tests, and start a program of hormone therapy.

Yet, in trying to access transition-related care, trans people regularly encounter unsustainably long waiting lists for trips to far-flung offices. Whether or not you’re able to access hormones is often up to the discretion of individual practitioners, who can simply decide they’re not comfortable writing a prescription. Beyond that, many jurisdictions don’t offer health coverage for transition-related care, and costs can be prohibitive.

Whether or not you’re able to access hormones is often up to the discretion of individual practitioners, who can simply decide they’re not comfortable writing a prescription.

According to a study by the Trans PULSE Project that focused on transgender health care in Ontario, self-medication with hormones is surprisingly common. Though their sample size is small, the results are still illuminating: of the 433 study participants, one-tenth reported using hormones they’d gotten from friends or from the Internet; 14 reported currently taking non-prescribed hormones; five participants had even attempted or performed surgical procedures on themselves, such as a DIY orchiectomy (removing the testicles) or mastectomy (removing breasts). Many participants cited a lack of money and past negative experiences with providers as causes for taking their transitions into their own hands.

Where we come from

Medical professionals tend to view being trans as a mental health issue. This was the logic underpinning the first gender identity clinics (GICs) in the 1960s – medical centres where sexologists and psychiatrists would study and assess incoming transgender patients. There, patients would receive counselling and/or a referral to an endocrinologist, provided they fit the diagnosis of something called gender identity disorder – which effectively classified being transgender as a medical condition. The label has since been scrapped, replaced with an expanded entry for “dysphoria” in the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) in 2013.

Since the 1990s, GICs have fallen by the wayside — where many people believe they belong. Though they’ve now been largely superseded by an approach based on informed consent, GICs once opened important doors for people to medically transition safely. They also, predictably, became sites where narratives about who and what a trans person could be were solidified.

Because of the diagnostic model GICs rested upon, and the costs associated with transition-related health care, they tended to reproduce a very specific image of what a transgender patient could and should look like: white, heterosexual, binary, and able-bodied. Often, people were turned away if they couldn’t fit the narrow criteria of these clinics. Two and a half years after the first gender-affirming surgery clinic in the U.S. was opened at the Johns Hopkins Hospital in 1966, it had performed gender-affirming surgeries on only 24 of 2,000 applicants.

They also, predictably, became sites where narratives about who and what a trans person could be were solidified.

That image has persisted, and shaped the common understanding of transitioning as a passage between two poles. Deviation from that script could mean the end of your journey. For example, patients had to prove that they were fully presenting as their gender in their social lives, including proving that they were employed as their gender; if you were masc (transmasculine), you had to be masc at all times, and be dating heterosexual women, or else you’d be dismissed as a confused lesbian.

The idea of being a gay trans person was almost unheard of. GICs had a strict policy forbidding treatment of queer trans people, with gatekeepers insisting that the two worlds should not collide. Lou Sullivan, a gay trans man based in San Francisco, had to fight with GICs across the U.S. for years before he found someone willing to prescribe him testosterone in 1979. Even then, it was considered scandalous within the medical community.

Sullivan was diagnosed as HIV-positive in 1986. Before dying in 1990, he wrote: “I took a certain pleasure in informing the gender clinic that even though their program told me I could not live as a Gay man, it looks like I’m going to die like one.”

Navigating gatekeepers

My friend Faith is a Black trans lesbian living in Toronto. She told me about her experience at CAMH, the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, which houses Ontario’s only GIC. There, she met with Kenneth Zucker – the doctor who helped create the definition of “dysphoria” for the DSM-5.

“After I explained to the doctor that I identified as a lesbian and played with feminine toys as a child, despite me repeatedly telling him about my dysphoria that’s spanned my entire life and [my] lack of attraction to men, he then proceeded to claim that I was most likely a ‘gay male in denial about his sexuality,’ and told me that he didn’t feel comfortable referring me to an endocrinologist,” Faith recalls. “I ended up breaking down in front of him and literally having to beg him to still refer me to an endocrinologist, which he eventually gave in to.”

The endocrinologist that Dr. Zucker sent her to suggested she start on a regimen of 100 mg of a drug called spironolactone. After three months on spiro, Faith would start her estrogen.

Spironolactone is an anti-androgen that reduces testosterone so that the body is more receptive to estrogen. But Faith’s blood work suggested that her baseline levels of both testosterone and estrogen were already quite low. Anti-androgens can cause side effects ranging from liver damage to weakness to mood swings – taking them without any other primary sex hormone in one’s system, some trans folks say, exacerbates these symptoms.

“I took a certain pleasure in informing the gender clinic that even though their program told me I could not live as a Gay man, it looks like I’m going to die like one.”

None of this information was shared with Faith, however. And even after increasingly higher doses of spiro, multiple blood tests showed that her estrogen levels continued to be low. “When I saw him three months later at the next appointment, he prescribed me 2 mg of estrogen,” she says. “Then I did some blood work, and my estrogen levels were low, so he decided to bump up only the spironolactone to 200 mg, then later up to 300 mg.”

Faith says she started feeling very weak and fatigued. She didn’t understand why her doctor had her on this dosage, and he didn’t explain it to her. The only forthcoming source of information was from other trans people. “I talked to my transfeminine friends on HRT [hormone replacement therapy], and they told me about and sent me research that showed that this was a dangerous decision by my doctor,” says Faith.

“At this point, I decided to take matters into my own hands and bump my estrogen dosage up to 4 mg and my spiro down to 100 mg without consulting the endocrinologist until our next appointment together,” Faith says.

The only forthcoming source of information was from other trans people.

This would not be the only time that Faith’s endocrinologist fought her, instead of listening to what she was telling him about her body and her needs. The second time concerned a request for progesterone, which many transfeminine people insist helps to increase breast growth and improve their sex drives. To a doctor, these things sound more like “wants” than “needs” and aren’t considered important. And because the research on HRT overwhelmingly deals with menopausal women, many doctors doubt the validity of giving progesterone to transfeminine people. Faith’s endocrinologist dismissed claims about its effectiveness as “solely anecdotal.”

“It was becoming increasingly obvious that I knew more about my body and that I’d done much more research on HRT than my doctor,” says Faith.

The unfortunate fact is that many doctors are deeply undereducated on trans health care. That puts the onus on trans patients to keep a close eye on their own health and mitigate any potential risks. As a result, many trans patients have done more research about trans health care than their doctors have, developing networks of shared information about hormones and specialists.

“Doctors don’t know anything about hormone shots,” says my friend P.J., a non-binary person living in Toronto. I was sitting at his kitchen table with him and my friend Nasash, a trans woman, eating strawberries. “They’ll tell you to inject in the hip, or the thigh, or the belly, and they don’t tell you how to stop leakage,” he says. “So for a lot of people, the shots are just not as effective.”

He tells me that he found out the best protocol by doing his own online research: shots should ideally be administered to the hip muscle, with the skin pushed together in one direction to prevent leakage.

“My current issue is that I don’t have a doctor and haven’t been able to get one for a year,” says Nasash, who lost health coverage after graduating from university last year. “I want to do investigations into my cortisol levels, to see if my organs are getting jumbled around by fat deposits that shouldn’t exist, which is a possible complication of spironolactone.”

The unfortunate fact is that many doctors are deeply undereducated on trans health care.

Nasash has an almost encyclopedic knowledge of hormones, and she knows exactly what she wants. But at this point, she’s less concerned with being restricted by her doctors, and more worried about her ability to even access the medical system to transition safely. “I’ve gone on and off these things unmonitored, but now I’m in a position where I need more medicine to do all the things I want, but I can’t really get any of it because I still need a family doctor and I can’t seem to get one,” she says.

Faith is in a similar boat. Due to scheduling conflicts, busy workdays, and financial obstacles, Faith missed her next appointment, and thus, her next prescription. Faith then turned to her community, borrowing hormones from friends and adjusting dosages as needed to help her achieve her personal transition goals.

Clinical courage

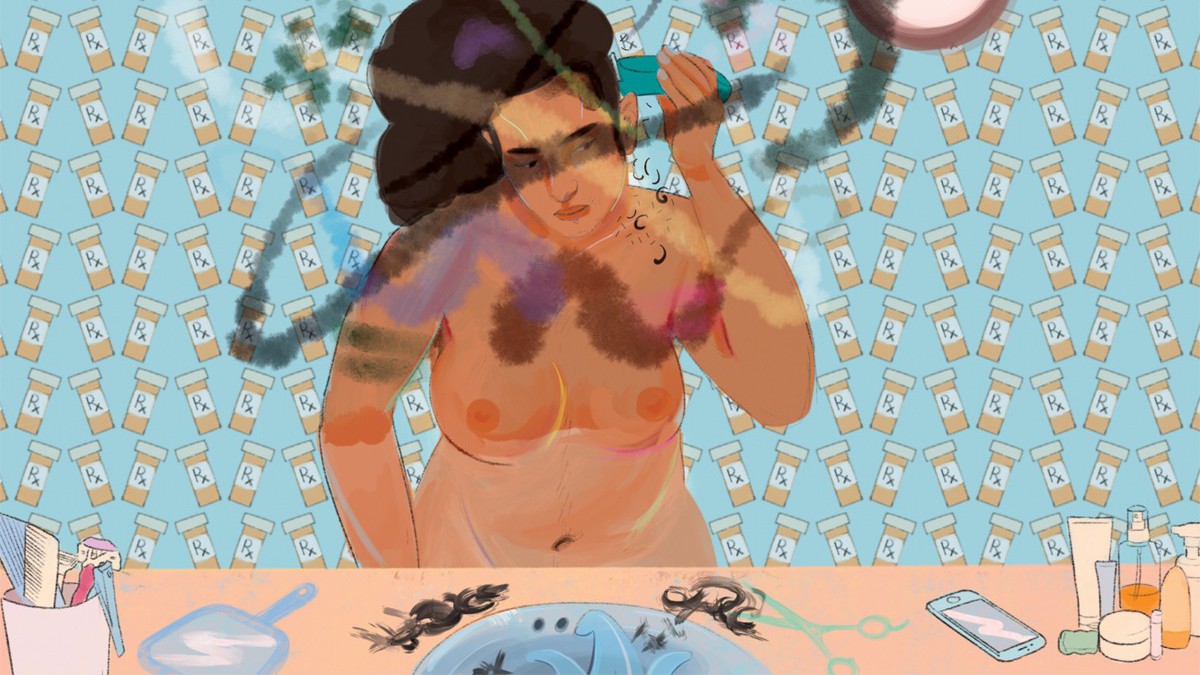

About two months into HRT, I began to lactate.

Nasash told me it could be a symptom of some larger chemical imbalance, and to keep an eye on it. My doctor said I shouldn’t worry. It went away the next day, but the damage had been done. I felt like a freak. A couple weeks after the lactation incident, I gave my hormones to my weed dealer — she loved them.

I stopped taking hormones because changes were coming too quickly, and I was scared for the future. I was cute as a boy, so was I really ready to become an ugly girl? When did I need to buy new clothes, and when would I find time to improve my makeup? Did I need a new name? When would my tits come in? How long did I need to be on hormones before I had to stop dating gay men, before I had to come out to my family, before I had to start saving for surgeries? Where was I on my “timeline,” and how would I know when I’d hit the point of no return?

I’m non-binary, but on paper, I was transitioning male to female. However, the times I felt most feminine, my most intuitively, inherently, absolutely a woman, were when I wore sweaters and caps, pressing flat what little chest I had, clean-shaven and barefaced, undeniably butch. I joked that I was transitioning into a trans man, but while transmasculine friends of mine were struggling with testosterone’s twin children of jawline acne and patchy peach fuzz, I was glowing. Estrogen does wonders for your skin.

I stopped taking hormones because changes were coming too quickly, and I was scared for the future.

One of the funny things about transitioning is that every doctor has a different opinion and is utterly confused by this when you bring it up. We’re in the age of the transsexual science experiment, as much a modern marvel of medicine as an act against god or a circus freak show. For a long time, what little scholarly information was available in the area of trans health care was limited to discussions of white subjects by white authors, which spawned a flurry of theorizing by social workers, psychologists, sexologists, and any other kind of cisgender thinker over what gender really meant, and what transition really entailed – a discourse that lives on and infects all forms of transgender health care, from psychotherapy to phalloplasty.

I talked about this with Cat Haines, a genderqueer trans woman based in Regina, whose activism focuses on harm reduction during transition. Speaking over the phone, Haines described doctors’ lack of “clinical courage” – the willingness to provide treatment even when it might be uncomfortable to do so. For cisgender practitioners, providing transition-related care – especially to someone who appears young or mentally ill – can feel like a huge transgression.

Depending on the context, doctors are balancing everything from their personal hang-ups and transphobic biases to a general lack of education on trans health care. There’s also the recent pearl-clutching in the media around de-transitioning, where one-off misrepresentations of trans people who regretted or reversed some aspect of their transition are used to imply that trans identities are flimsy and risky. As a result, doctors may worry about lawsuits or defamation. In short, clinical courage is hard to come by.

“Not treating a patient can cause more harm than treating a patient when you feel uncomfortable,” says Haines. “There are going to be times when you will be uncomfortable. You’re going to have to work through that discomfort in order to ensure that you’re providing care, because you’re the only doctor around.”

In short, clinical courage is hard to come by.

Haines tells me that in places like Saskatchewan, clinical courage is especially necessary because access to care is so sparse. “There are very few general practitioners who are prescribing hormones, and very few who are culturally competent – I can think of maybe three or four throughout the province,” says Haines.

Beyond a binary

Everyone that I talked to for this article considers themselves to be non-binary or genderqueer in some way – either as a label on its own, or as a description of their relationship to transmasculinity or -femininity more broadly. Which is interesting, because the idea of a non-binary transition is somewhat new to mainstream discussion, though people have been expressing genders in complicated ways for millennia.

There’s this idea that non-binary people don’t transition, or that being non-binary is a phase on our way to “man” or “woman.” It’s obviously untrue. But all the same, I’ve been having trouble thinking about what transitioning might look like for me as a non-binary person – figuring that out is part of what brought me to write this article.

At the time of writing, I’ve been back on estrogen for about three weeks. My doctor is working with me, according to goals we discussed together. This way, I can go slowly, and gradually make changes as I feel I need to.

There’s this idea that non-binary people don’t transition, or that being non-binary is a phase on our way to “man” or “woman.”

I spoke on the phone to a non-binary person in Toronto named Kat – their relationship with testosterone is similar to my relationship with estrogen. “I’m not trying to transition all the way,” they say, “I just want to feel more like myself.”

Kat got their testosterone prescription as treatment for low sex drive – or at least, that’s what they told their doctor. Kat told me that they found they needed to lie because their doctor was unwilling to consider administering testosterone to someone he perceived to be doing perfectly fine living as their assigned gender. “I look like an attractive woman, and people say to me, ‘why would you want to give that up?’” says Kat. “I’ve gotten it so many times, including from a doctor once. He said, ‘why would you want to change anything? You look very good.’ The doctor basically implied that I was ‘performing’ well as a female.”

Kat’s experience is not unique. In fact, many people told me about incidents of lying to doctors in order to get treatment for a fictional “need” when they were denied treatment for their actual “want.”

Winnie Wang also identifies as non-binary, and menstruation makes them dysphoric, so they use birth control to suppress their periods. Birth control is hormone-based, and relies on a cycle of hormones and placebos. If you only take the hormones and not the placebos, you can effectively skip your period. Wang got birth control through their doctor, but said they needed it for cramps and heavy flow.

According to Wang, lying felt like the only sensible option. The clinic had given them significant cause for apprehension. “I was scared of them being judgmental, or not prescribing me the meds at all. I had an unrelated visit with another doctor at the clinic who mis-gendered me, and asked me if I was schizophrenic because I wanted to use they/them pronouns,” says Wang. “So after that, I was definitely never going to tell the truth about why I wanted birth control.”

According to Wang, lying felt like the only sensible option.

Wang has been lying ever since, both about their need for birth control and about their dosages. “After I told one doctor that I was using it to skip my periods, she said it was ‘unsafe’ and ‘unnatural,’ despite me not experiencing side effects,” says Wang. “It felt more unnatural to me to have a period.”

I brought this up with another non-binary person named Fable, a New Orleans-based mechanic who gets their hormones from the Internet. For them, self-medicating was an opportunity to connect more deeply with their body – what they wanted, how they were feeling, what worked for them, what felt right. They described a sense of groundedness and autonomy that they’d never achieved through the medical system. It was a homecoming.

There are all kinds of reasons people step away from the medical establishment. Most of them are rooted in necessity – issues of finances, discrimination, limitation, and access. We lie to our doctors because that’s what they understand. People are more comfortable assessing our degree of suffering in our bodies than they are acknowledging our potential to expand beyond what we’ve been given: that you can want to be a woman, or want to be a man, or neither, or both – or, shockingly, that you might know what you want better than they do. That you might not know what you want, but you’re discovering. That you can be anything and anyone, and that you deserve to be able to do so safely – not because you’ve passed some test, but because you are alive. Because you want it.

Some interviewees asked to change their names to protect their privacy. J.D. used his initials, and Nasash used a pseudonym. In all other cases, the names used are the names the interviewees provided, some of which included surnames and some of which did not.