As both an organizer and participant over the years, I have long seen the need for social spaces but find there is a lack of support and dialogue with others working on similar projects. When I learned that a Social Spaces Summit was being organized by the Purple Thistle Institute in Vancouver, I was excited to make the trip. According to the organizers, “the summit was intended for members of radical social centers, info-shops, libraries, student resource centers, co-ops, artist-run spaces, anyone who works in a physical space that aims for radical social and political justice.”

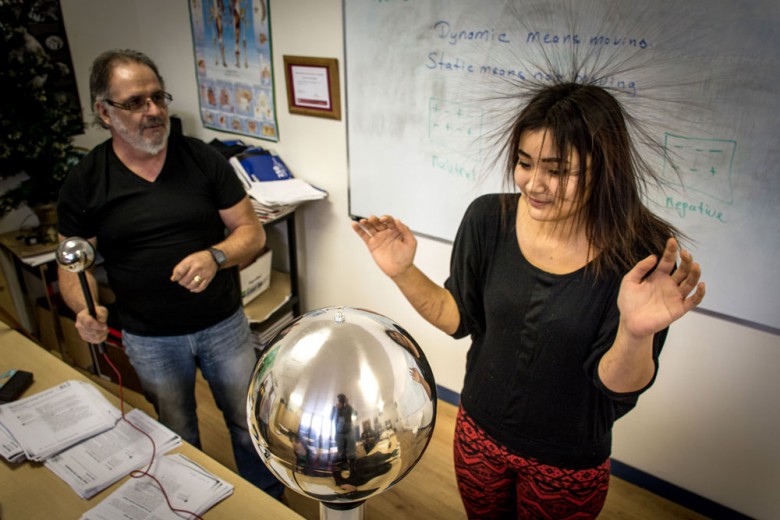

The Summit was based on a popular education framework, the belief that we are all learners and we all have knowledge to share. Workshops were proposed by anyone who was interested and drew on the collective wisdom of people who work in radical social spaces all over the country. A whiteboard in the main hall had a schedule drawn on it with empty time slots where people could spontaneously add a suggested discussion topic and location throughout the weekend. This way, many of the participants were also facilitators, which made for lots of dynamic exchange.

With over fifty of us from places including New York State, Seattle, Portland, Victoria, Salt Spring Island, Guelph, Winnipeg, Calgary, and from various projects in Vancouver, it was evident that there are many people reflecting on social spaces, questioning the meaning of our work as organizers and wanting to explore how we can do it better. Workshops happened simultaneously at different “social space” venues throughout the weekend, including Rhizome Café, The Dogwood, The Stag Library and Toast Collective Space. It was great to showcase examples of spaces in Vancouver, while evoking the complex reasons why these spaces exist and why organizers pour their energy into creating and sustaining them.

Anti-Oppression and decolonization in social spaces

Along with conversation about the nuts and bolts of creating and maintaining spaces, discussion throughout the weekend of the Social Spaces Summit often returned to decolonization and resisting gentrification. Since physical location and social interaction are so integral to the work of radical social spaces, deconstructing larger processes of colonization and systemic oppression framed the content of the Summit.

Collectively organized “social spaces” often function as a place where we can apply our theory, test our analysis, and develop skills to work together on projects and campaigns for social change. Our centres interface with neighbourhoods and people, ecology, and habitat. Physical place connects with history, human habitation, colonization, gentrification, and the complex processes of development and displacement.

“Wandering Through Colonial Space” was a walking tour led by Cole Smith, a participant of the summer 2011 Purple Thistle Institute program, who explained that “this method is primarily informed by the Dene First Nations and how they map through story. Also by concepts that originate with European thought: the situationalist practice of psychogeography and Henri Lefebvre’s concept of the production of space.” The walk explored the East Vancouver neighbourhood of Strathcona, where five of the social space venues featured in the summit are located. Participants examined the surroundings, noticing traces of colonization, deconstructed settler colonialism, discussed what decolonization actually looks like, and became aware of our places within the framework of decolonization and anti-oppression.

“Keepin’ It Real: Learning to face ourselves for stronger communities,” a workshop at the Summit facilitated by Ruby Smith Díaz, was based on the premise that “oppression can be hard to unlearn, and sometimes even our biggest efforts to be anti-oppressive can still be hurtful to others.” At another workshop called “Control of the Commons”, concerned with how gentrification affects neighbourhoods and the role of social spaces in this process, Smith Díaz contributed recommendations for how spaces can be more inclusive in the form of a poster titled “Solidarity > Integration.” Her message was: “Many radical/anti-capitalist spaces are often very white or ‘sub-culturey,’ leaving many to wonder, ‘Why aren’t they coming to our events?’” Instead of this phrasing, she suggested, “Try asking yourselves, ‘Why aren’t I supporting other peoples’ events?,’ keep a gentle and open heart, and be willing to look critically at historical/generational trauma that still has a very real and present effect on relationships between white folks and Indigenous and people of colour.”

Purple Thistle, a place to root ourselves

Because the concept of social centres can be somewhat amorphous and difficult to define, due to the diverse contexts in which they arise, it helped to have the Social Spaces Summit based out of such a strong and well established centre as the Purple Thistle. Talking with one of the core organizers, Carla Bergman, shed light on the long term strategy involved in operating a social space.

The Purple Thistle Centre is a youth-run community centre for arts and activism. Tucked into the landscape of concrete and metal warehouses in the industrial area of Strathcona in East Vancouver, “The Thistle” is a colourful hive of activity, arts and crafts, guerrilla gardening, workshops and self-publishing. According to Bergman, “The centre is a physical space to root ourselves, a place to work together, and a site to learn new ways for radical organizing for social change.” The Purple Thistle Institute, a radical collective interested in building counter-institutional space and horizontal relationships around learning critical social theory and praxis, is an offshoot of the Centre and was responsible for making the summit happen.

According to Bergman, “framing the Purple Thistle as an arts based project has done it’s purpose of keeping it going (and fundable!) for a dozen years.” She says it particularly supports their desire to invite youth from all ideological backgrounds. Bergman says, “Being explicitly anti-capitalist and anti-authoritarian offers up a different way for youth, who run the day-to-day operations of the centre, to engage together while at the same time learning organizing skills and many other skills.”

In describing the Thistle’s approach, Bergman said, “One of our goals is being a truly convivial space and really striving to connect to the folks who live near and around the centre. We do pretty good, especially with our drop-in participants, but the core collective is often made up of folks who are a lot alike in their predilections. There’s lots of reasons for this and I think a lot of it has to do with the explicit radical way in which we organize. We like to say we are politically overt but not ideological pure – we are always looking at and reworking this.”

Beyond the summit

If the goal of the Summit was to cross-pollinate, share resources, challenge our praxis, and gain skills, then it was successful. Working on sustaining a space financially, physically, and collectively can be frustrating and exhausting. It’s affirming to know there is a network of people working towards similar goals, overcoming challenges and finding fulfillment in the work.

We ended the last session of the weekend summit sitting in a circle, and then started stacking chairs and cleaning up the space. Everyone pitched in to wash dishes, mop the floor and haul boxes out to the van. We were all familiar with this routine, chatting while sweeping up, and acknowledged that the best conversation usually happens in the kitchen, doing the work, making things happen. Exchanging email addresses and hatching plans for future get-togethers, the space was alive with the buzz of “social spaces.” We asked each other questions: “Who will take the initiative to organize the next summit? How could we make it better?” We came away with tools, insights and contacts to supplement our practice beyond the summit.

The Social Spaces Summit was a kind of meta-social space, trying out the many principles and practices used in DIY and radical communities. These are places where the messy, dynamic process of community converges with radical analysis of social and environmental justice. Through the intersections, strategies for change emerge. By drawing attention to their role, self-managed radical social spaces might be better able to function as strategic infrastructure in larger social movements.

_780_520_90_s_c1.jpg)