“In my view the law plays a sufficient contributory role in preventing a prostitute from taking steps that could reduce the risk of such violence.”

With these concluding remarks by Justice Susan Himel, the laws that kept sex work illegal in Ontario were struck down in the fall of 2010. The ruling, however, has been stayed, pending an appeal by the federal government that’s scheduled to begin in June, 2011.

If the appeal is unsuccessful and these laws do indeed fall in Ontario, it would likely set off a chain of challenges across the country, which would be a major victory for sex workers and those advocating for their rights.

Decriminalizing prostitution in Canada

Prostitution itself has never been illegal in Canada, but almost everything that makes sex work possible is: Section 210 of the Criminal Code regarding bawdy houses makes it illegal to run, work in, or be inside of any building where sexual services are exchanged for money; Section 212 (1)(j) outlaws living off the avails of prostitution, thus barring prostitutes and their dependants from living off of their earnings; and Section 213 (1)(c) outlaws communicating for the purposes of soliciting, thus criminalizing any negotiation about rates and time of sexual services.

Based on extended research on the arguments both for and against the criminalization of sex work, Justice Himel ultimately concluded that these three laws disallow sex workers the freedom to negotiate the terms of their own safety, thereby enabling the violence that is often perpetrated against them by clients.

Many women’s rights organizations have denounced the decriminalization ruling, arguing that sex work is inherently violent, and that to decriminalize it legalizes violence against women.

But organizations comprised of women in the sex industry, who have experienced criminalization and violence first-hand, have generally been supportive of Justice Himel’s decision. Émilie Laliberté, director of Stella, a by-and-for sex workers’ rights organization based in Montreal, argues that the perspective of feminist organizations which view all sex work as abuse, coercion and exploitation is based on ideology rather than fact. And besides, she says, there are other parts of the Criminal Code that address these issues. “In the Criminal Code there are many other sections that fight exploitation, profiting based on coercion, and profiting based on juveniles. [Himel] kept these things in purposefully.”

Violence against sex workers is endemic, and nightmarish scenarios such as the Pickton murders in B.C. exemplify the social marginalization that makes sex workers’ lives seemingly more expendable. Laliberté argues that criminalization puts workers at particular risk of danger by imposing a structural vulnerability. “These women* get targeted for sexual assault because they are not protected, and do not have any rights. Just the fact that women are being seen as criminals sends a message to society that they are less than human.”

Criminalization of sex workers creates a perceived institutional impunity for those who perpetrate violence against them, and inhibits sex workers from reporting violence for fear of arrest. “We’ve seen too many times women in the industry subjected to mandatory arrest after reporting sexual aggression,” says Laliberté. Women are therefore doubly victimized, first by the perpetrator, and then by the criminal justice system.

This rights-free vacuum that sex workers inhabit is especially troubling for women and trans women, who already face a higher level of societal stigma for not conforming to gender norms. The history of racism and colonization that places Indigenous women at far higher levels of social marginalization also increases their vulnerability to violence both from clients and police officers.

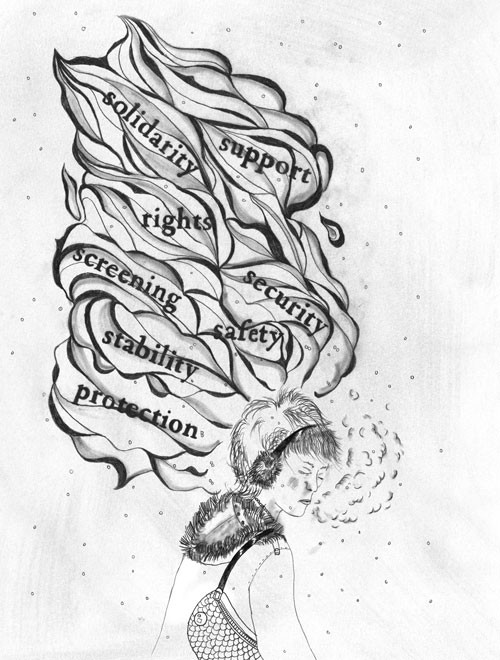

The fact that criminalization impedes women’s ability to reduce the risk of violence and aggression against them was Himel’s main reason for striking down sections 210, 212(1)(j) and 213(1)(c). Laliberté notes that indeed, with Himel’s ruling stayed, “All of the ways to increase your workplace security are illegal right now.”

Regarding the section outlawing bawdy houses, Himel stated in her ruling that “the evidence suggests that working in-call is the safest way to sell sex; yet, prostitutes who attempt to increase their level of safety by working in-call face criminal sanction.”

Laliberté concurs. “We see in putting together our Bad Tricks list [Stella’s anonymous list of abusive clients] that most of the aggression takes place on the streets. When you work from inside you control your environment and you can put in place more security measures.”

Though ‘living off the avails’ of prostitution might conjure up images of abusive pimps forcing women to work for them and living off of their money, this law also criminalizes common security measures taken by women, such as hiring drivers to take them from place to place, security guards for their workplace, or managers to pre-screen clients. Himel noted the danger of criminalizing security measures in her concluding remarks, arguing that “Prostitution, including legal out-call work, may be made less dangerous if a prostitute is allowed to hire an assistant or a bodyguard; yet, such business relationships are illegal due to the living on the avails of prostitution provision.” The abusive coercion and financial exploitation often perpetrated by pimps remains illegal elsewhere in the Criminal Code.

The successful removal of the third section, barring communication for the purposes of soliciting, would be a major cause for celebration for sex workers’ rights organizations. If removed, it would mean that women could negotiate rates without fear before agreeing to take clients. This is particularly significant for women working on the street, who already face the most violence. Presently, for fear of getting arrested, women often get into a vehicle without being able to first screen the client, negotiate fair rates and services, or discuss safe sex. According to Laliberté, “They just jump in, and then they go into back alleys and darker areas where there are less people around so as not to be seen by the police.”

“Because of this we see more STIs and more violence,” adds Laliberté. The World AIDS Campaign recently published a report which substantiates this observation, stating that criminalization increases women’s vulnerability to contracting HIV because they are less able to negotiate safe sex practices. Justice Himel’s concluding remarks concur and go further, stating that this section not only inhibits women’s capacity to protect themselves, but also undermines their right to freedom of expression guaranteed under the Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

Case Study: Decriminalization in New Zealand

“Because of decriminalization you have this expectation now that we should be safe. In a criminalized environment, if something disturbing happened, we had no choice, really, but to shrug it off. In a decriminalized environment, people can act, they can say ‘I deserve occupational safety and health, I’m not going to put up with this. Who can I ring?’”

—Catherine, member of the New Zealand Prostitutes Collective

In a landmark decision in 2003, the laws that rendered sex work illegal in New Zealand, nearly identical to those singled out by Justice Himel, were removed, making New Zealand the first country in the world to decriminalize sex work. At the same time, the Prostitution Reform Act was introduced to ensure sex workers’ rights and needs were being met. This act specifically bars managers from forcing sex workers to have intercourse with clients, bans any kind of coercion using financial or physical threats, allows women to work together collectively out of the location of their choosing, and provides sex workers with workplace safety benefits and the ability to file unemployment claims.

Catherine is a member of the New Zealand Prostitutes Collective, a sex workers’ rights advocacy organization that played a large role in the decriminalization of sex work and the introduction of the Prostitution Reform Act. When asked how decriminalization has affected her working conditions, Catherine states emphatically, “In my day of working it was common for us to be arrested, be publicly shamed, and to know that there was nothing we could do if we were faced with violence when working – all of those terrible things that happened in a criminalized environment. Have conditions improved? Short answer: enormously!”

Since decriminalization, if a woman is forced to have sex with a client against her will through the use of threats or fines, it is the manager or the client who faces criminal prosecution – up to 14 years of incarceration – and the sex worker can report this free from the fear of arrest. Recent studies demonstrate that women’s perceived levels of safety have drastically increased since 2003: before decriminalization, 37 per cent of sex workers felt they could refuse a client. This increased to 62 per cent within four years. According to Catherine, “It used to be common for clients to pretend to be the police and force people into things. Now sex workers can turn down requests and feel safe.”

Though local politicians are continually making notable efforts to re-criminalize sex work, the concept that sex workers, especially on the street level, should have rights is now widely accepted in much of New Zealand society.

Catherine explains that many basic exploitative workplace practices that were the norm under criminalization, such as unjust fining or forced 14-hour shifts, can now be challenged in much the same way as a parking ticket. “If your manager unfairly takes your money, you can fill out a form saying you’re disputing the [theft]. Your boss will talk to the adjudicator, and these adjudicators are generally in favour of the sex worker in those scenarios. It’s both practical and extremely empowering.”

The Prostitution Reform Act offers sex workers a variety of measures to ensure workplace safety, from mediation to pressing charges criminally, depending on the severity of events and the desire of the sex worker involved. Safe sex practices are part of the legislation, posters about safer sex methods are mandatory in all brothels, and brothel operators are required by law to support sex workers’ right to safe sex, rather than pressuring them into unsafe sex, refusing access to condoms, or hiding condoms in case of police raids, as happens in Canada.

Catherine notes that these new norms provide a level of self-determination to sex workers previously unheard of under criminalization. “People stand up to unfair conditions. They are now empowered to be appalled.”

In the lead-up to decriminalization, many New Zealanders feared a huge influx of sex workers into the country. Research commissioned by the Ministry of Justice in 2005, with participation from New Zealand police offices and the New Zealand Prostitutes Collective, demonstrates that there was in fact no influx. The city of Christchurch, which had large numbers of sex workers both prior to and following decriminalization, saw no increase in the number of sex workers from 1999 to 2006.

Upcoming Battles

According to an Angus Reid poll conducted for Maclean’s magazine in 2009, nearly 50 per cent of Canadians believe that prostitution should not be punished. While there are some calling for Canada to adopt the Swedish model, which criminalizes clients but not prostitutes, polling shows that only 8 per cent of Canadians support this option. Laliberté critiques this model, asking, “How can a worker work safely while she has to go on the black market to find a client? It’s not respecting the choice of women to do these exchanges. The police should be arresting assaulters and not consensual adults negotiating sexual services.”

With the appeal to Himel’s ruling set to begin in June, 2011, those in support of decriminalization face a difficult battle. These sections falling in Ontario would likely lead to their eventual challenging all across Canada, and the Conservative government and the mainstream feminist organizations that do not support decriminalization will no doubt do everything in their power to stop Ontario from setting such a precedent.

According to Laliberté, one of the upcoming challenges for sex workers’ rights organizations in Ontario will be to make interventions in the appeal. For Stella, this will mean focusing on educating both politicians and the public. To that end, Stella is currently coordinating a project titled Stella Deboutte, which involves collecting, transcribing, and publishing interviews with sex workers on how criminalization affects their lives.

Laliberté stresses that it is sex workers, and not those who claim to speak for them, who should be the ones determining the laws that govern their bodies. “It’s sex workers that need to be in control of their own destiny and not at the mercy of laws that endanger them. We need a consultation with sex workers in all sectors on decriminalization, from strippers to women working on the street, on how we can enable them to work in safety and in dignity. It’s been forever that we are criminalized so organizing will be quite tricky. But we’re looking forward to it.”

*This article is focused on sex workers who identify as, or conduct their sex work as, women. For this reason, the terms ‘women’ and ‘sex workers’ are often used interchangeably. Violence against male-identified sex workers is an under-explored topic that also deserves critical analysis but does not fit into the size and scope of this article.