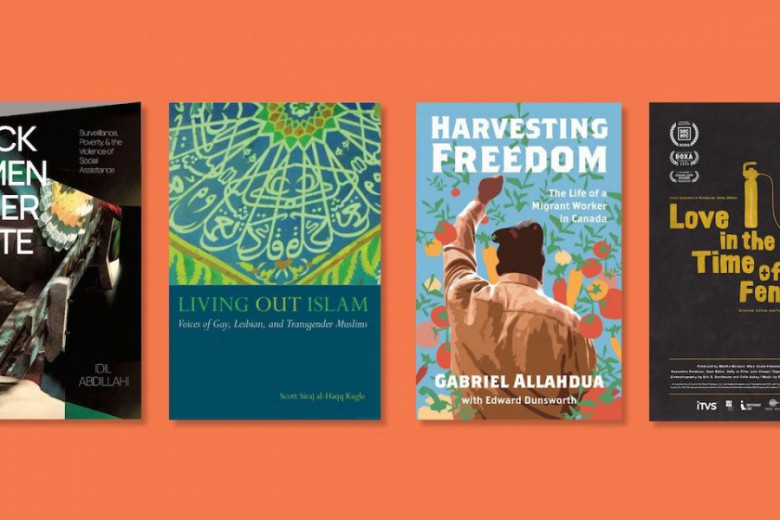

Photo by Alejandro Rodriguez.

On a late August day last year, under a hot clear sun, Ottawa’s queer and trans communities took to the streets with their kaleidoscope of flags and flooded the downtown core with rainbows.

But this year, at every step among them – up and down the march, and all along the rows of spectators – were Palestine flags and the iconic stripe-and-fishnet stitching of the keffiyeh.

To anyone who knows our communities, this isn’t surprising. For the vast majority of us, first-hand experiences of discrimination lead naturally to progressive values of social justice, anti-oppression, resistance, and solidarity. Since October 2023, many community members have marched and organized under Palestinian flags against Israel’s brutal genocidal assault on Gaza – sometimes as human beings of conscience, sometimes explicitly from a queer political identity responding to the calls to action of queer Palestinian organizations. The queer left tradition of Palestine solidarity has deep roots in the organizing of queer Palestinians and their allies, alongside a well-articulated set of critiques of Israel and of settler-colonial and imperialist power that long predate the current moment.

But in Ottawa, queer solidarity with Palestine wasn’t a counterforce on the outside of a business-as-usual Pride Week. Instead, many of the usual corporations and politicians stayed home while grand marshal Haley Robinson sported a keffiyeh, Queers for Palestine made up one of the largest contingents in the march, and solidarity politics permeated what Capital Pride volunteer Jamie* described to me as “a harmonious marching for queer and trans solidarity and celebration, as well as holding space for Palestine.”

The common aphorism that “the first Pride was a riot” was not a given; it was an achievement of gay liberation organizers, keen to write resistance into the mythology of our movement’s history.

This mass display of Palestine solidarity was anything but a thin gloss over an otherwise status-quo Pride. Rather, it was a genuine popular display of queer liberation – a remarkably successful experience in mainstreaming the international solidarity traditions of the queer left and queer of colour organizing. This unequivocal success of a truly political Pride suggests that now is the time for the queer left traditions of solidarity and coalition-building across communities under attack to move from an oppositional current in our spaces to being a long-term strategy for our communities in the face of existential right-wing threats to come.

The struggle for Pride

Pride in North America has always been contested, a terrain of struggle concerning our communities’ political horizons.

Following the bitter, bombastic June 1969 riots at Greenwich Village’s Stonewall Inn – a rare community space for working-class and street-involved queers, especially queers of colour – gay liberation organizers saw an opportunity for a new height of movement-building, and launched into action.

Keffiyehs and rainbow flags in downtown Ottawa during Capital Pride 2024. Photo by Anik Faisal.

Within a month, New York City’s newly formed Gay Liberation Front (GLF) – which inspired a wave of similarly named organizations across the U.S. and in Canada – had begun to build a legend and a new political practice around the Stonewall Riots. GLF members played a big role in organizing the first commemoration of Stonewall – the first Pride march – as the Christopher Street Liberation Day March of June 1970. The common aphorism that “the first Pride was a riot” was not a given; it was an achievement of gay liberation organizers, keen to write resistance into the mythology of our movement’s history.

Already in 1970, different political visions for the swelling movement had taken organizational expressions.

"It becomes clear that homosexual liberation cannot develop in a vacuum,” wrote two members of the leftist GLF. “We are one of many oppressed groups, the roots of whose oppression lies within a diseased capitalist system […] we must now join forces with our sisters and brothers in the Movement so that we can begin the struggle for total human liberation." For the newly organized queer left, our communities needed to claim their place among other oppressed groups and to commit to strategic coalition building and organizing for power in the streets.

On the other hand, liberal bearers of Gay Activists Alliance (GAA) banners interpreted their project much more narrowly. In a call for funding published in GAY magazine, the editors described the GAA as “not intend[ing] to ‘overthrow the system’ but to improve life for homosexual men and women.” This meant fighting for community-specific reforms within the framework of existing political and social structures, especially through a political strategy of visibility.

These basic schisms across political and strategic lines – and, inevitably, across race and class – have had long afterlives in the history of Pride, with the GAA’s liberal strategy and politics increasingly dominating Pride marches worldwide.

Pride in the Capital

Ottawa too has known Pride as a site of struggle. “No longer are we going to petition others to give us our rights. We’re here to demand them as equal citizens on our own terms,” declared Charlie Hill at the city’s (and country’s) first ever public demonstration for gay rights in 1971, at August’s “We Demand” rally on Parliament Hill. Although many key organizers, like militants from Toronto Gay Action and the Front de libération homosexuel, had coalesced and sharpened their politics and tactics in the wake of gay liberation’s post-Stonewall moment, the rally was not linked to the June commemoration and institutionalization of Stonewall as queer resistance. Its demands, too, reflected the narrower focus and liberal horizon seen from groups like the GAA.

In 2015, Capital Pride was refounded as a partnership with the Bank Street Business Improvement Area. Community members, especially queers of colour, responded with critiques about Ottawa’s Pride space as whitewashed, corporatized, and undemocratic. These critiques, and the relentless organizing of mainly queer Black activists that carried them forward, achieved at least one important gain: Capital Pride’s 2017 policy of excluding off-duty police officers from participation in the yearly march, unless they left their uniforms at home.

But that same year, coverage of Capital Pride was dominated above all by the news of Justin Trudeau’s participation, as the first sitting prime minister in history – flanked by Canada’s chief of the defence staff, in what the media hailed as Pride “flex[ing] its political muscle.”

“I think it sends a strong message about inclusion [...] I think we’ve come a long way,” said Capital Pride’s communications director, capturing the reaction and mood from proponents of the decades-long strategy of queer integration into dominant political and economic structures. “Today, Pride brings everyone together to celebrate our community.”

A very different note was struck by an organizer with the community group Reclaiming Pride, who spoke of a need for “holding Capital Pride accountable for the things they do and the steps they take to include community within their celebration. And changing the dynamic from this fun capitalist party to also focus on queer [and] trans liberation.” The 2017 march’s height of visibility and inclusion, welcomed by some, was arguably more removed than ever from the original vision of liberation for all, across lines of struggle for racial and class justice, and in coalition and relationship with other communities in resistance.

Moving the status quo

Flash forward to summer 2024, unfolding in the shadow of months of Israel’s genocide in Palestine. In Canadian cities and internationally, Jamie told me, “Prides were moving the status quo” – ignoring well-articulated demands from solidarity groups, and usually facing a mass reckoning on the day of the march in the form of a blockade or disruption. June in Toronto was typical: the Coalition Against Pinkwashing iced out by an undemocratic and immovable Pride Toronto pulled off a well-organized disruption, and succeeded in cutting Canada’s largest Pride march short by an hour. Similar scenes played out in Vancouver, Montreal, Winnipeg and elsewhere.

In some smaller Canadian towns, a different possibility emerged. More community-driven and democratic, Pride boards in Fredericton, St. John’s, Halifax, and Hamilton put out meaningful statements of Palestine solidarity and committed themselves to genuine divestment efforts, up to and including challenging the established role of the genocide-invested TD Bank in sponsoring Pride festivities across the country.

On August 6, a week and a half before Ottawa’s Pride Week, Capital Pride released a “Statement in Solidarity with Palestine.” In measured tones rooted in solidarity values, the statement named the genocide in Gaza and committed the organization to four relatively soft actions: recognizing the ongoing genocide publicly during the march; pushing for a ceasefire; hosting a queer Arab event; and integrating the Palestinian demand for boycott, divestment, sanctions.

These commitments fell well short of what queer solidarity organizers in other cities had demanded, but reactions from the powerful were swift and furious. Erstwhile allies in political office were soon to declare they would boycott: Ottawa’s mayor Mark Sutcliffe and the federal and provincial Liberal Parties were foremost among them. Along with politicians, major corporations registered the limits of their support for queer solidarity. Prominent among these was supermarket chain Loblaws, a leading sponsor of the year’s festivities (infamous for exploiting consumers through their bread price-fixing scheme.)

Giants of political and economic power in Ottawa may have thought that their loud retractions of support would successfully pressure Capital Pride to apologize for their statement. Instead, they galvanized their own constituencies and particularly their own workers.

The loud public withdrawal of politicians and corporations from the community’s flagship event raised questions about their pledged support to begin with.

“When I was hearing the mayor’s not coming to Pride, my instinct was, it’s not for you,” says Jamie. “Pride is not a place for allies in quotation marks.” They point out that as a community member, whether you agree or disagree with the “non-queer journalists and non-queer political actors going, ‘Pride has said something unacceptable,’ […] you’re [still] left asking, ‘why has a non-queer person decided what is and isn’t acceptable at Pride?”

As the weeks passed, solidarity with Pride and with the community came from wholly different quarters – particularly, organized labour. Along with politicians and corporations, major Ottawa-area public-sector employers had also withdrawn. These included giants of the city’s health and education sectors – university, school, and hospital boards – as well as the Public Service Pride Network (PSPN), a network that claims to speak for all 2SLGBTQIA+ public servants employed by the Government of Canada. Following the PSPN’s lead and that of the ruling Liberals, Ottawa's government departments cancelled their participation en masse.

A callback to Stonewall as a reminder of the roots of Pride and against its corporatization seen at Capital Pride in Ottawa, 2024. Photo by Anik Faisal.

But the space vacated by the city’s employers was readily filled by their workers, in a groundswell of popular and bottom-up support. Nearly 450 Ottawa-area health workers put out a solidarity letter, pro-Palestine education and university workers self-organized in support, and public service unions including the Public Service Alliance of Canada and the Canadian Association of Professional Employees headed a massive contingent of public servants flying union colours along with the rainbows and Palestinian flags.

Giants of political and economic power in Ottawa may have thought that their loud retractions of support would successfully pressure Capital Pride to apologize for their statement. Instead, they galvanized their own constituencies and particularly their own workers. Jamie’s concern was, “Are queer people still going? […] Is the queer teacher still going to go? The queer nurse? The queer public servant? Because queer people are part of these organizations that [institutionally] have power, and that are choosing not to participate, but are their workers going? And I think you saw in large numbers they still were.”

By Pride Week, Capital Pride had not budged on its statement. Many powerful actors did not show up, but plenty of the people they claimed to speak for did. Palestine solidarity was woven throughout a uniquely – although far from completely – de-corporatized Pride. As grand marshal Robinson breathlessly told reporters: "Thank you for having me here, thank you for allowing me to walk with my Two-Spirit and queer Palestinian folks […] Pride to me has always been about creating space and using voices to help marginalized people here and globally.” The tonal contrast to the much more apolitical festival criticized in years past was stark, as was the cross-section of our communities and allies at Pride’s heart. Both suggested a mass display in the tradition of queer liberation, loudly privileging and centring solidarities over single-issue politics and visibility in the eyes of the city’s power players. Along the way, Capital Pride may have shed light on which political horizon and which strategy has a future and which does not.

The future of Pride

The pro-Palestine political content hints at some of the concrete possibilities for a queer liberationist political project in cities like Ottawa. In spite of the capital’s reputation as a white government town, it’s also a rapidly changing city with large and growing Black and Arab communities and a uniquely large and long-established Lebanese diaspora. The strength, cohesion, and deep roots of these communities in Ottawa have not always translated to organized challenges to the dominant whiteness of many of Ottawa’s major political and cultural spaces and institutions – including Pride itself. But many aspects of the city’s culture, such as the historic and present strength of Palestine solidarity mass politics in Ottawa’s streets – including in August 2024 – can’t be understood without recognizing these communities, and their pride and endurance in resistance and anti-racist struggle.

Celebration, too, takes on a different meaning when it’s embedded in a politics of defiance and solidarity.

In recent decades, Arab and Muslim communities across Canada have been key targets of right-populist scapegoating and campaigns of sanctioned racism and discrimination. Over the last year, too, pro-Israel advocacy and public discourse has aggressively deployed the tropes of Islamophobia and anti-Arab racism – often, but not always, in the corrosive forms unique to anti-Palestinian racism.

Queer communities are not immune to being conscripted for and participating in these projects. Conversely, Arab and Muslim communities are not immune to being targeted by right-wing hate movements directed at queer and trans people, particularly those that rely on misinformation to win populations over to support for anti-trans policies in the name of parental rights. But the shared experience of scapegoating and persecution, by many of the same powerful societal actors, suggests an objective basis for deep and meaningful solidarity and coalition building.

Queer and trans Arabs and Muslims have been and will be at the centre and leadership of such projects. This is a key lesson from the long history of queer of colour organizing, which draws a line from complex lived experiences that can’t be understood through just one identity category to transformative political projects that leave behind a single-issue framework.

Celebration, too, takes on a different meaning when it’s embedded in a politics of defiance and solidarity. The week’s queer of colour programming – especially the Zaffa queer Arab drag showcase and a triumphant outdoor set by Arab/Southwest Asian and North African (SWANA) DJ collective Laylit – was framed by Palestine solidarity politics and suffused with an atmosphere of genuine political community building.

As a person with SWANA roots, Jamie adds, “It felt like the day and the weekend still had queer joy – I think Pride 2024 became so politicized in solidarity with Palestine, but it wasn’t just that. I think, had I gone to that as my first Pride ever, I might have been like, ‘whoa, this is so representative and so political’ and I think it might have changed what I as a young person saw Pride could be.” With this, we caught a real glimpse of what might be possible in refounding Pride on a politics of solidarity and coalition building toward what the GLF called total human liberation.

After Capital Pride 2024, Queers for Palestine declared that they had “witnessed a type of Pride that we haven’t seen in years. We witnessed a Pride that belonged to the people.” In context, this was no exaggeration; a pro-Palestine Pride was won and defended successfully in Canada’s capital. This experience can and should be a source of courage, hope, and inspiration for our communities as we face emboldened far-right projects that rely on division and scapegoating, and as we strategize and fight for a better future in times of global and national crisis. The apolitical celebrations of single-issue gay liberalism are behind us. Instead of fighting to get them back, we can choose to centre queer of colour politics, to untether ourselves from rainbow capitalism, and to reclaim the best of the queer liberationist tradition: its vision of interconnected forms of struggle and of liberation for all, and its strategies of solidarity, coalition building, and bottom-up organizing for the power to fight for ourselves and our communities.

To choose that, as Pride did for one beautiful summer week in Ottawa, is to honour and hold fidelity to queer love and queer community globally – but it’s also our best chance of building out our position to defend ourselves and to free ourselves.

*Jamie is a pseudonym and their role is kept vague due to privacy concerns.