Under colonial rule, Ghana’s multiple traditional systems of justice were replaced by a single, expensive, incarceration-based penal system. Now, 52 years independent and among the poorest 15 per cent of nations, Ghana is at the mercy of foreign countries for financial support in maintaining its overcrowded prisons, retraining prison staff and educating prisoners in an effort to upgrade a system of punishment that is falling into disfavour in the wealthier nations from which it originates.

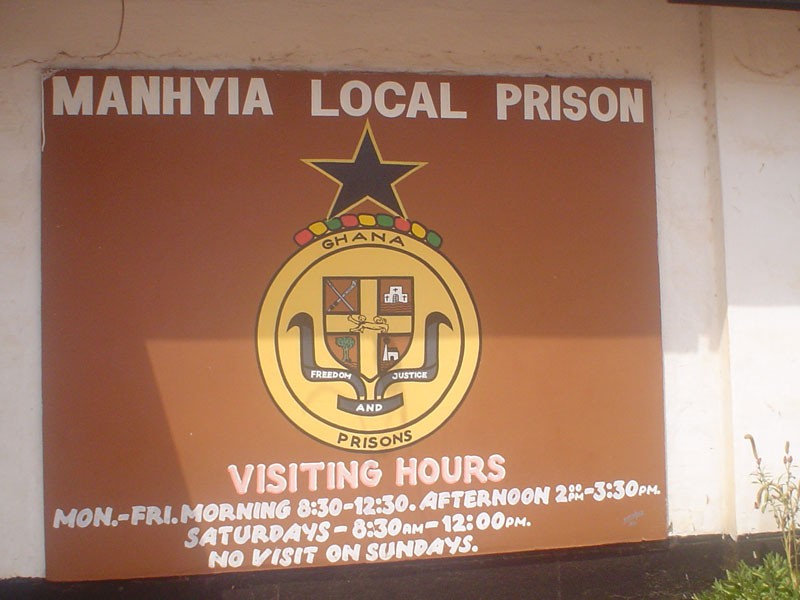

Robert Awolugutu wrote several books about prayer before he realized that many of those he thought might benefit most from his words, his prisoners, cannot read. As the Officer-in-Charge at Manhyia Prison in Kumasi, Ghana, he is responsible for the welfare of 193 men living in a prison built for half that number.

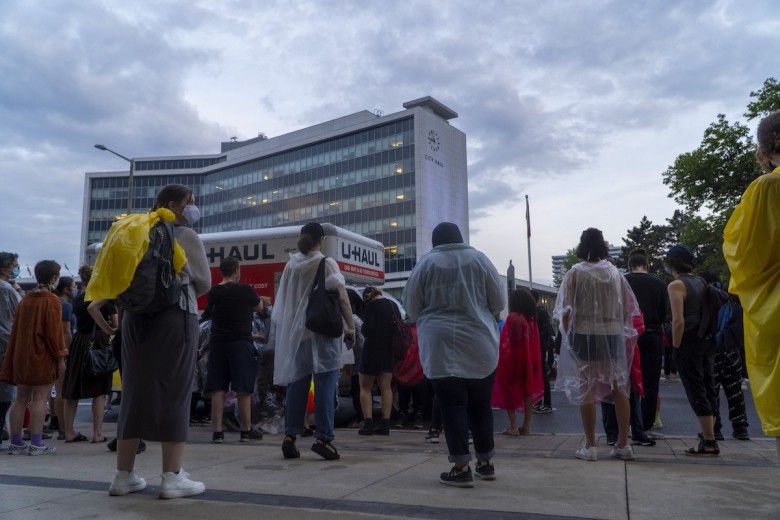

“They still have all their human rights, aside from their liberty,” Awolugutu told a group of visiting Canadians from the United Nations Development Programme. The Canadians were there to talk prison reform, including literacy training for prisoners and human rights training for prison staff. The Ghanaian state can’t afford to fund either on its own, despite seeing the value of both, which creates yet another international development paradox.

Were Ghana able to make use of its own abundance of natural resources instead of being at the mercy of multinational commodity traders, it could afford to properly educate and employ its own citizens, negating the extreme variances in wealth that usually cause crime. Were extreme poverty in Ghana thus eliminated, the crimes that would still exist could then be resolved in an expedited legal system that included fair representation for all, fully trained prison staff and a more effective restitutive and restorative justice system – without having to rely on international institutions like the UN Development Programme.

Ghana, like other poor countries, faces a Catch-22. As long as poverty and inequity remain, it is dependent on rich nations, each with a vested interest in maintaining its own wealth, to help it reform its key institutions, all of which are hampered by the poverty that was first created by the colonialism of those now-donor nations.

Nsawam’s prisoner-teachers

In spite of the extremely limited resources at his disposal, Awolugutu had already taken steps to improve the welfare of his prisoners. Disturbed by the two per cent literacy rate in his jail, he enlisted the help of two prisoner-teachers, Williams Apaabey and Christopher Tanye, and set up a prison literacy program. The program had 15 students and a chalkboard, but no chalk, books, markers or pens. One of the founding prisoner-teachers has since been released as part of Ghana’s 50th anniversary amnesty program. The other has experience teaching at the junior secondary level, but no training in adult education.

“There is nothing wrong with our program except lack of materials,” Tanye told me.

The guards in both the men’s and women’s prisons in Kumasi echoed that sentiment, as did senior staff members of the Ghana Prisons Service. The visiting UNDP staff were told that the idea of enhancing prison literacy was not new, just underfunded.

One of the first groups in Ghana to consider prisoner literacy programming was the discharge board of Nsawam Prison, Ghana’s largest medium-security jail. Nsawam was originally designed to hold 600 men. It now holds more than 2,700.

Nsawam’s discharge board is made up of volunteers, pastors and church congregation members as well as prison staff. In its work to prepare soon-to-be-released prisoners for life on the outside, the board concluded that illiteracy is a serious problem facing prisoners.

“Illiteracy kept the prisoners from participating fully in society in the first place,” Awolugutu said.

Literacy, crime and income inequality

While Ghana’s literacy rate is below 60 per cent, among prisoners the rate is considerably lower. Some of the Nsawam staff estimated the literacy rate in the prison to be less than 10 per cent, although no in-depth assessments have been made.

Nsawam’s discharge board convinced the Ghana Prisons Service that literacy training will reduce the crime rate. W. K. Asiedu, Director General of Prisons, and Israel Tsegah, Director of Human Resource Development, say that many of Ghana’s prisoners commit crimes because they lack education and have few opportunities to earn a living. The theory is that when unemployment and poverty increase, crime also increases. The statistical data supports this view.

The full story, however, is more complex. Recent research in Africa and North America has indicated that income disparity – the co-existence of extreme wealth alongside extreme poverty – is an even better predictor of crime than is poverty. A textbook example is found in Johannesburg, South Africa, where violent crime is most common just outside of gated communities. Drivers are often attacked and robbed as they stop to enter their security codes.

“It has to do with the distribution of poverty,” according to Professor Stephen Ayidiya, who explained his work to me in his office at the University of Ghana, Department of Social Work. He has observed that disparity breeds desperation and envy. “If you live in town and you don’t have a job to earn your daily bread, and you see people with nice big houses and cars and you feel they are no better than you, there is a factor of revenge to the crime.”

Some criminals believe that the wealth of their victims has not been acquired rightfully, nullifying their own guilt. “If they see a big house they think it must be a cocaine house, or bought with stolen money or by a corrupt politician,” Ayidiya explained. With Ghana performing below the international average in all corruption indices, this popular belief that wealthy people are dishonest is no surprise.

Recidivism and overcrowding

Literacy training alone, of course, will not solve the problems of Ghana’s justice system. But it may help reduce recidivism (the tendency of released prisoners to commit crimes again). In a recent report to the Ghana Prisons Service, it was noted that repeat offenders in Nigeria have considerably higher rates of illiteracy than first-timers.

Reduced recidivism in turn reduces overcrowding in prisons. Ghana has an approximate prison population of 18,000 living in facilities designed to accommodate 4,000. Incarcerating prisoners 40 to a cell is not uncommon.

At Manhyia Prison, the area designated as common space is barely big enough to host a table tennis game. The jail itself, like so many of Ghana’s prison facilities, was actually never intended to hold prisoners. The entire prison was originally a waiting room in the King of Ashanti’s palace, and became a jail only when the King changed residences.

This is typical of Ghanaian prisons, which have not been expanded since independence in 1957. They are not only overcrowded but in a general state of decay, with little expectation of infrastructure renewal on the horizon.

The Kumasi Women’s Prison is as overcrowded as the men’s prison. It too was built for purposes other than incarceration. And like the men’s prison, it also has an under-resourced literacy program.

The women’s program’s one advantage is that the women’s teacher, Second Officer Mary Uumadi, is a young and dedicated prison guard. As a full-time employee, she won’t likely be released from her teaching duties anytime soon.

Uumadi has taught at the Kumasi Women’s Prison since 2005. She has her hands full teaching basic literacy to 12 of the jail’s 55 prisoners. Her pupils have varying levels of education, but most cannot read at all.

“Mary makes it very interesting,” Josephine Fredua Agyemang, Officer-in-Charge at the women’s prison, told me. “They are learning and we are always taking in new students.”

But once these women are released from jail, most have little chance of attaining employment outside the informal economy of hawkers, hairdressers, bread-bakers and other low-paid service providers.

Still, Ghana Prisons Service consultant Miia Suokonautio, originally from Scarborough, Ontario, believes that the program itself enhances prisoners’ sense of self-worth. “Some studies suggest an increased knowledge of self can lead to reduced criminalized activity,” she explained.

Suokonautio helped develop a Ghana-wide literacy training program that will be coupled with human rights training for prison guards at all levels. The female and male guards I spoke with expressed eagerness for more training to build on what they had learned.

Disturbed by the two percent literacy rate in his jail, Awolugutu (centre) enlisted the help of two prisoner-teachers and set up a prison literacy program.

Human rights still apply

The human rights training that prison staff have already received, which encourages staff to see their work environment from a prisoner’s perspective, got guards thinking of ways to improve the lives of prisoners, such as establishing literacy programs. A few years ago, 16 senior staff from Manhyia attended a two-week human rights training program in Nigeria. “It helped us treat people better,” Awolugutu, the most senior of the 16, explained.

According to Awolugutu, there is an old belief among guards that prisoners forfeit not only their liberty, but all other human rights too. Because of training, this belief no longer applies at Manhyia. “We don’t allow beatings; being here is their punishment,” he said.

Agyemang and her staff also attended UNICEF-sponsored human rights training last year in the capital, Accra. “We liked it very much,” she said. “It was very interesting – mostly about child rights, but we learned adult rights too.” In Kumasi Women’s Prison there are three young children with their mothers. The prison allows children to stay with their mothers and promotes breastfeeding.

The most significant lesson of the training, according to Agyemang, “was learning how to put ourselves in prisoners’ shoes, understand that they are confused, disoriented, scared. It sensitized us, so we understood that prisoners have rights.” It was this training that got the guards thinking about how to help prisoners solve their problems before leaving jail.

As a result, the prison offers several vocational training programs, including hairdressing, bread-baking, crocheting, dressmaking, doormat making, and palm oil crushing. Women also have the opportunity to learn about sexual health from the Planned Parenthood Association of Ghana, one of few non-Christian volunteer groups working directly in Ghanaian prisons.

The Planned Parenthood Association of Ghana started teaching about self-esteem, sexual health, family planning, and STD prevention in the Kumasi Women’s Prison. The agency has since been admitted to speak with the men as well.

Planned Parenthood still faces significant institutional resistance, however, particularly in the men’s prisons. As Planned Parenthood Regional Coordinator Elsie Ayeh explains, “we run AIDS education but we can’t acknowledge sodomy. And we can’t distribute condoms. We can only focus on self-esteem and hygiene.”

Last year, Ghana Prisons Service finally did acknowledge that sodomy exists in its jails, but added that “severe sanctions” are applied to those involved, as part of the new focus on corrections over punishment. Homosexuality is illegal everywhere in Ghana. Same-sex partners in jails are offered counselling, but still no condoms.

The prevalence of AIDS in Ghana’s prisons, however, has never been denied. A recent series of tests at Kumasi Central Prison found seven cases of AIDS among the 57 prisoners. Four other men had died of AIDS in the previous six months. Yet Kumasi Central Prison, the largest in the region, would not allow Planned Parenthood staff to speak with its prisoners.

At the other two Kumasi jails, the Planned Parenthood Association of Ghana continues its use of HIV testing and education kits, training guards and peer educators to talk about the risk of AIDS, though they cannot distribute condoms. Some prison staff point out that had it not been for human rights advocacy, even these small steps may have been impossible.

Alternatives to incarceration

The focus on human rights training has led to a recognition of the need for deeper structural changes to Ghana’s justice system. The UN Development Programme and the Ghana Prisons Service received an important piece of feedback during a pilot two-day workshop for prison guards on human rights. More than 60 per cent of the guards expressed the belief that “more important than human rights training is providing prisons with adequate resources, such as staff and space.” Indeed, human rights workers agree that increased human rights sensitization of staff will accomplish little on its own if the acute overcrowding situation in Ghana’s prisons is not addressed.

Although the UN Development Programme is providing seed money for the literacy and human rights initiatives, improving facilities is not on its list of projects. Perhaps development experts fear the possibility that if more money goes into building and expanding prisons, more prisoners will be sent there.

If there could possibly be an upside to the overcrowding, perhaps it’s that it forces the courts to consider other options, such as restitutive justice or non-custodial sentencing. As a result, Ghana Prisons Service has increasingly focused on measures such as mediation between perpetrator and victim, as well as alternative sentencing options such as probation, community service and fines.

Despite these efforts, every few years the government of Ghana is forced to grant amnesty to some prisoners to alleviate overcrowding. Last year 1,000 were released; two years ago the number was 2,000.

Many of these freed prisoners receive amnesty for crimes for which they have not actually been convicted. Close to half of Ghanaian prisoners have never been convicted; they are still awaiting trial. Many others are serving multi-year sentences for crimes most Canadians would consider minor, like possession of marijuana.

Visiting lawyers from the Canadian groups Journalists for Human Rights and Canadian Lawyers Abroad were struck by the slow pace of the courts. Defence attorneys, who are not paid for by the state, require a transportation retainer (which one judge wryly called a “reminder”) in order to show up to a hearing. The poor are usually forced to defend themselves, and are generally ill-equipped for the task.

The Canadian lawyers also noted an abundance of prisoner rights advocacy groups, many of which are working in isolation. According to their final report, “Five organizations: Legal Aid, Legal Resource Centre, Prisoners Rehabilitation and Welfare Action, Centre for Public Interest Law, and Commonwealth Health Rights Initiative, are all organisations involved in separate yet extremely similar projects advocating for prisoners’ rights… . They are all asking for funding from the same donors and therefore have the inherent need to compete and succeed in their own independent projects in order to receive more funds.” The Ghana Prisons Service sergeants and visiting Canadian lawyers both recognize that resources could be better allocated to speeding court proceedings, fighting corruption in the legal system, and coordinating the efforts of prisoner rights groups.

If Ghana is successful in expediting its justice system, the number of prisoners could be reduced by more than half. However, that would still leave the overall population at more than double capacity. Despite reform efforts, prisons in Ghana, as in Canada, remain an expensive, unworkable non-solution to the complex societal desires of punishment, security, and reform – as Michel Foucault termed it, “the detestable solution, which one seems unable to do without.”