Postcards from the End of America

By Linh Dinh

Seven Stories Press, 2017

Bob, a 60-year-old Safeway employee from Florence, Oregon, is counting on the store staying afloat. “At my age,” he says, “it will be hard to get hired again. I don’t want to move to the city to find another job.” Before working at Safeway, he worked 31 years in a sawmill. Bob blames environmentalists on the east coast, trying to protect the endangered spotted owl, for the death of the industry that once employed his town. “Since our logging industry is mostly dead, we have to buy lumber from overseas, from people who really don’t give a hoot about the environment.”

Bob is one of the many disenfranchised workers interviewed in Linh Dinh’s book, _Postcards from the End of America_. The book contains collected essays and observations made through several years of domestic travel, originally published in various online journals, like long, descriptive letters home from towns of crumbling infrastructure as though they were tourist hotspots.

While there was widespread controversy in the 1990s about West Coast logging, Postcards analyzes Oregon and other former industrial and manufacturing centres in the U.S. that have been hollowed out by governments and corporate rule. Rather than pitting environmental justice against economic justice, Dinh impresses upon readers that environmental and other progressive movements need to accommodate and support workers of all industries; the common cause of both economic and environmental precarity is capital, Dinh points out, not social movements.

Across the U.S., cities that were once economic boom towns are now facing unemployment, poverty, homelessness, addiction, and crime. Places such as Trenton, New Jersey, one of many visited by Dinh, is famous for the Warren Street bridge over the Delaware River adorned with the lit-up phrase TRENTON MAKES, THE WORLD TAKES; it is a reminder that Trenton was once a manufacturing hub for products used around the world. A hundred years later, the slogan reads more like a bitter homage to trade deals that have left towns like Trenton in the dust.

Dinh travels by bus and train, stopping in former and current industrial metropolises such as Osceola, Iowa; Kensington, Pennsylvania; and Williston, North Dakota, snapping photos of individuals he meets (20 of which appear in full colour in the book), to survey the social landscapes. He often wanders to the nearest bar, for no matter the size or unemployment rate of a town, there is always a vendor of cheap alcohol that carries with it a rough but undeniable sense of community. These places are often the best indicator of the health and economic state of a society. In bars and on street corners, in buses and under bridges, Dinh interviews individuals tethered to the rising and falling industries that have ruled and abandoned their hometowns. Dinh gives voice to those who are rarely heard in mainstream journalism, sharing their stories of underemployment and struggle, occasionally offering simple context for how things got to be the way they are in each particular city. Many he meets blame governments for their hardships, while others, like Misfit, a bartender in Chester, Pennsylvania, believe reports that the country is in an economic recovery. Dinh lays bare pieces of their stories, at times abruptly, without forcing too much commentary, allowing the weight of their lived experience to be felt by the reader.

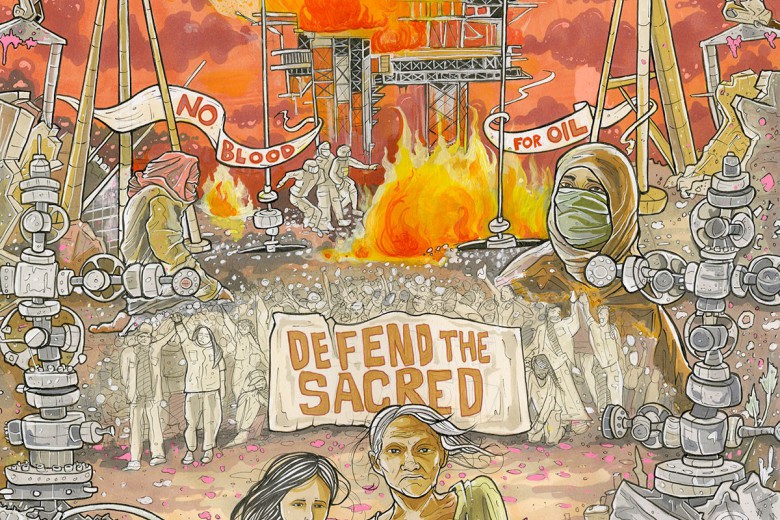

Dinh never makes his way to Canada, but his portraits of urban and industrial America could easily be those of Canada’s industrial and extractive regions. With Trudeau’s Liberal government approving pipelines and maintaining their commitment to the Trans-Pacific Partnership, Canadian communities are not immune from being wholly abandoned by both government and its corporate rulers, leaving the Canadian countryside filled with towns and social-scapes like those in Dinh’s postcards; in fact, this is already happening. The resource bust in Western Canada has left thousands of people without work and entire communities struggling to meet their needs, even while political campaigns left and right hawk promises of prosperity. When the industries dry up, the companies that once put towns on the map move off to exploit the land elsewhere, leaving the communities with skeletal social supports and no means of income. One admirer of Dinh’s writing, Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Chris Hedges, refers to these areas as sacrifice zones: places in which entire communities are permanently impaired by profit-chasing corporations that fatally ignore the effects of their decisions on human life, the environment, and communities. In selling off public assets to corporate control and privatizating once-public services, Trudeau and his provincial and municipal counterparts are in many ways propelling Canada into an economic situation mirroring the one described by Dinh.

Each entry was written in the final years of the Obama administration and the beginning of the Trump campaign phenomenon. Dinh’s purposeful portraiture of the financial ruin and the concurrent rise of Trump are not coincidental. Canada, with a shallow, amoral federal Liberal government that sold out its own citizenry to pipeline interests, and broke its own promises for economic and racial equality, is only setting itself up for a Trump-like oligarch to respond to the discontented masses whose employment situations will reflect those highlighted in Dinh’s prophetic book.

Dinh has no illusions about what has put so many Americans into unrecoverable poverty and poor health, and his exposé of the decline of the American empire is a call to Canadians to organize for real and lasting change in our own social, environmental, and economic landscape.