Amita Bhatia, of Vahana Films, is an independent filmmaker. Briarpatch contributor Fathima Cader caught up with Bhatia to talk about Disconsolatus, a full-length science-fiction psychodrama that she wrote and directed. It was inspired by the poetry of Palestinian writer Mahmoud Darwish.

Why do you make films?

I write and make films that audiences will find both relatable and challenging. Technologically speaking, filmmaking has never been more accessible – it’s quite feasible these days to make high-quality, feature-length films on a micro-budget. This opens up the industry to stories and filmmakers like never before. A young director whose story doesn’t fit the status quo and whose uncle isn’t so-and-so in the biz might get a chance to sit in the director’s chair. Said director might be a woman (four per cent of feature-film directors are women in Canada), or even a woman of colour.

What’s Disconsolatus about? What’s the story behind the title?

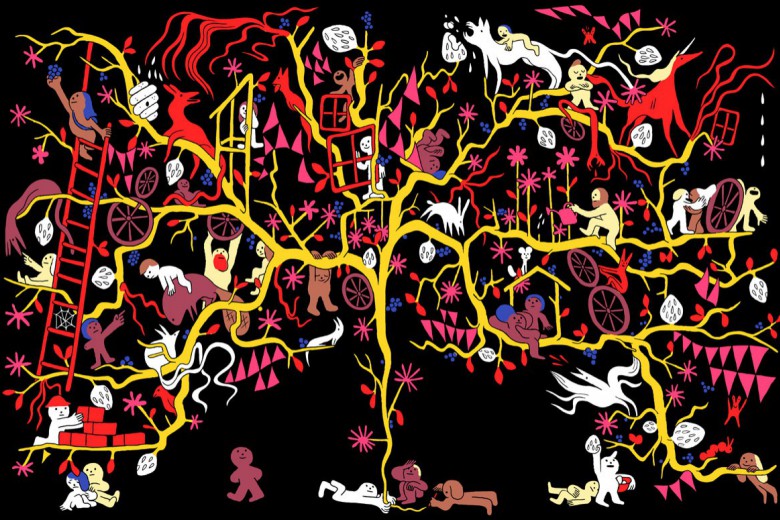

Disconsolatus is a semi-linear, poetic sci-fi that follows the subconscious journey of Dana, a Palestinian-Canadian artist who has become accustomed to popping pills to cope with her depressive state. With her family far away in occupied Palestine, the artist becomes increasingly isolated in her Toronto home. She learns of an outbreak of “Disconsolatus” in the city, which requires mandatory evacuations, medication, and quarantine. The symptoms of this bizarre infection coincidentally resemble that of Dana’s general depressive state. As the lines between her dreamworld and reality become blurred, Dana plunges into a mystical subconscious world riddled with poetry, the supernatural, and interdimensional portals. This subconscious journey ultimately leads to the critical moment of Dana’s personal awakening, one where she must choose between surreality and life.

“Disconsolatus” is a medieval Latin term for someone incapable of consolation. It is relevant to the predicament of our lead character, but it also sounds like an infectious disease, doesn’t it? I think the fictional disease that we portray in this film is something that all audiences can relate to, either directly or through someone close to them. Similarly, the film touches on the themes of the power of big pharma and the institution of psychiatry.

Rumour has it that you made the film in under a week with less than $10,000. How did you pull that off?

It’s true. People see the four-minute teaser we put online and don’t believe that we shot this thing for next to nothing. It definitely wasn’t easy. Once I had a screenplay, I was faced with the challenge of funding a Darwish-inspired poetic sci-fi with a Palestinian lead in Canada. After sharing a few laughs with myself, I decided to enlist some of the smartest people I knew, who were foolish enough to take on the task. We all volunteered our time and devoted funds from our personal savings, primarily toward equipment and location costs. We kept costs low by renting a single camera and some cool lenses, as well as minimal lighting equipment for one week at a four-day rate. We shot 24/7 so that we could complete all the scenes in the seven days. A lot of our scenes were shot between 3AM and 6AM, when we could use the empty streets of Toronto as our film set. Working with a microscopic film budget requires a whole other level of creativity. Our actors rehearsed for a month before shoot week. We planned and planned meticulously so that we could pull off this truly insane challenge. We were all zombies by the end of it.

Why does Darwish’s poetry play such a large role in this film?

In my opinion, the late Mahmoud Darwish possessed unparalleled artistry. Many of his poems utilize surrealistic imagery that blend the personal and political with fantasy. So it is no surprise that many artists have interpreted his work into different mediums. I came across “I didn’t apologize to the well” this summer and I read it over and over again. It moved me deeply and evoked some fantastic imagery: oracles, mystical wells, and gazelles. It inspired me creatively and I put on the hat of a surrealist writer and a couple of days later I had a screenplay in my hand. The only viable film genre that would satisfy this kind of storytelling was the sci-fi genre. So in Disconsolatus, we have a Palestinian artist who actually has Darwish’s poetry and imagery pop up in her subconscious world. This is presented through sci-fi staples like telekinesis, telepathy, and interdimensional travel. The poem, as I read it, also deals with a personal awakening, one that I connected with on many levels.

Why did you want your protagonist to be Palestinian?

It made sense, given the Darwish reference, but it was also a deliberate choice. When we are in times where the very existence of a Palestinian people is absurdly up for debate, it’s very easy for a filmmaker to make a simple choice that challenges such a ridiculous notion. Disconsolatus isn’t overtly political – it’s a sweet little science fiction film that takes a psychoanalytical angle, but organically embodies things that are personal and that I am passionate about. I should note that finding a Palestinian Canadian actress was not easy – hopefully films like this will change that.

What was filming this in Toronto like? Any memorable spots?

Perhaps the only people pleased with the ridiculous summer construction that plagues Toronto every year are guerilla filmmakers. We might not have big studios, but we can be assured that a few major streets will be closed off to traffic year after year, waiting to be filmed. _Disconsolatus_’ plotline involves an empty city under quarantine so we really needed the streets to be completely abandoned. We also shot in some unusual places in the early morning hours. Trinity Square, outside Eaton’s Center, has this beautiful historic well that is unbelievably cinematic, which we used as the mystical water-well from Darwish’s poem. The graffiti alleys on Queen Street West are like a labyrinth straight out of a graphic novel. For the scenes involving infected patients in the psychiatric complex, we used Toronto’s infamous “hedonist” club, Wicked, which just happened to host a number of caged beds. I guess you could say that was memorable.

What are the film’s next steps?

We have finished shooting the film and have put a rough cut together. Right now, we are working in the sound studio. We are looking to crowd-fund the next stages of post-production, which requires some technical expertise and costs that we can’t get around, like colour correction and pro sound. We want to continue the volunteer-based community feel by raising the money from the public to finally get Disconsolatus out to festivals and audiences around the globe. I encourage people who are interested in the film and this kind of filmmaking to contribute what they can to our Indiegogo campaign, even if it’s just coffee change. I’m not going to shock anyone when I say that the film industry in North America isn’t exactly gushing over a film inspired by Darwish with a Palestinian main character, so we are really relying on the support of individuals to help us bring Disconsolatus to the finish line. We can’t accomplish this without you. Fans and contributors can get regular updates off Facebook and Twitter pages.

Do you have any advice for other emerging filmmakers?

Put it on paper and then film it. Even if it’s with your iPhone. Even if your iPhone is 3G. Then make another one. And get used to eating canned beans, because some of your grocery money is undoubtedly going to pay for your film.