As I drive the 20 kilometres through farmland and small towns north of London, Ontario, to visit O’Shea’s Farm, I realize early on that I am not visiting an ordinary farm. GPS devices don’t generally recognize family farms by name as mine does. Roadside signs also assure me that O’Shea’s Farm is mere kilometres away.

O’Shea’s Farm, near Granton, Ontario, is and is not extraordinary. The barns are painted classic white and green; it’s neat; and, on first glance, it seems to be a quintessential Ontario farm. A mixed farm known for its produce and the famous O’Shea Irish pickle, it raises pigs and sheep and harvests cash crops like corn and beans. But O’Shea’s Farm, which has been in the family since 1832, is also now a tourist attraction.

I am greeted at the end of the laneway by a towering straw-bale man. Later, proprietor Jeremy O’Shea shows me around the land and tells me about all the attractions his farm boasts: wagon rides, winter sleigh rides, an enchanted forest, a Junior Farmers’ training centre for toddlers (with toddler-sized tractors), a bale pyramid for climbing, a corn maze, a bunny hutch and more. When I mention that my favourite thing about growing up on a farm was playing in the barn loft on the Tarzan-style rope, O’Shea smiles and leads me to his barn loft, which is called Play in the Hay and features slides, climbing tires and a rope.

Rise of Agri-tourism

Having grown up in rural Ontario with an understanding of the economic difficulty of pursuing farming as a full-time occupation, I have been impressed by the number of my friends with agricultural roots who have remained committed to farming. Operating within a global food system that favours cheap imports over quality, local produce, local farmers are turning to all kinds of creative endeavours in order to supplement their farm income and remain financially viable.

Agri-tourism includes a variety of tourist practices and types of agriculture. Across the country, agri-tourist destinations and events include rural festivals like the Pumpkin Festival in Smoky Lake, Alberta, the Apple Blossom Festival in Nova Scotia’s Annapolis Valley, and the Fall Flavours Festival on Prince Edward Island. There are also organized farm tours, like Manitoba’s Open Farm Day and the circle farm tours in British Columbia’s Fraser Valley. Agri-tourist destinations also include small town fairs and large agricultural exhibitions like the Western Canadian Agribition in Regina and the Royal Agricultural Winter Fair in Toronto.

The O’Sheas aren’t the first in their region to incorporate tourism into their farming practice. Within Middlesex County in southwestern Ontario, agri-tourist destinations include apiaries, maple sugar bushes with seasonal pancake houses, pumpkin patches, corn mazes, haunted houses, horse-drawn wagon and sleigh rides, and berry farms. Other well-developed agri-tourist destinations in the O’Sheas’ neighbourhood include Apple Land Station, an apple orchard in Thorndale that offers educational programs for school children and a plethora of tourist activities, and the apiaries at Clovermead Adventure Farm in Aylmer, which offers birthday parties, bee barrel train rides, go-carting, zip-lining and educational programs on beekeeping.

While there is a long history of some agri-tourist ventures like pick-your-own fruit farms, contemporary agri-tourist ventures like O’Shea’s Farm are responding to specific contemporary realities: urban ignorance about food production and the economic need to instill a love and appreciation for local food in local customers.

Fields of splendour

Agriculture is generally not understood to be spectacular. People don’t often stop to admire cornfields, wheat fields or pastures unless aliens have landed in them or a man builds a baseball diamond to conjure ghosts (as in the 1989 sports drama Field of Dreams set in the middle of an Iowa cornfield, which, incidentally, became a major tourist attraction after the release of the movie). University of Alberta philosopher Allen Carlson calls these endless monocultures “blandscapes.” How does tourism become appropriate within these familiar, seemingly unspectacular landscapes?

Sociologist John Urry argues that things become subject to the tourist gaze through difference. In a context where fewer and fewer Canadians have direct access to farms through grandparents or other relatives, living and working in agriculture seems to have become a distinctly peculiar way of life. Ignorance of agriculture seems to suggest an intense disregard for the basic workings of life, which is understandably frustrating for farmers. But many farmers are beginning to subvert and tap into urban ignorance and disconnection through agri-tourism.

Agri-tourism is a perfect articulation of what tourism scholar Dean MacCannell terms “alienated leisure.” MacCannell uses this term to describe phenomena like visiting factories and other forms of industrial tourism. For MacCannell, alienated leisure is a symptom of a society in which work is no longer of primary importance. That people are willing to pay to pick their own strawberries or to visit an agriculture museum for a chance to milk a goat demonstrates how alienated we are from these basic forms of labour and food production.

Nostalgic or political?

Critics might argue that agri-tourist destinations risk contributing to romantic and nostalgic notions of farm life, with urbanites visiting farms for brief periods of time to get their rural fix before returning to their comfortably disconnected lives in the city. If visitors to O’Shea’s Farm perceive this farm to be the norm in contemporary agriculture and their experience of playing in the hay or picking strawberries as kin to agricultural labour, they would be mistaken. However, the intent of many agri-tourist ventures is political rather than nostalgic.

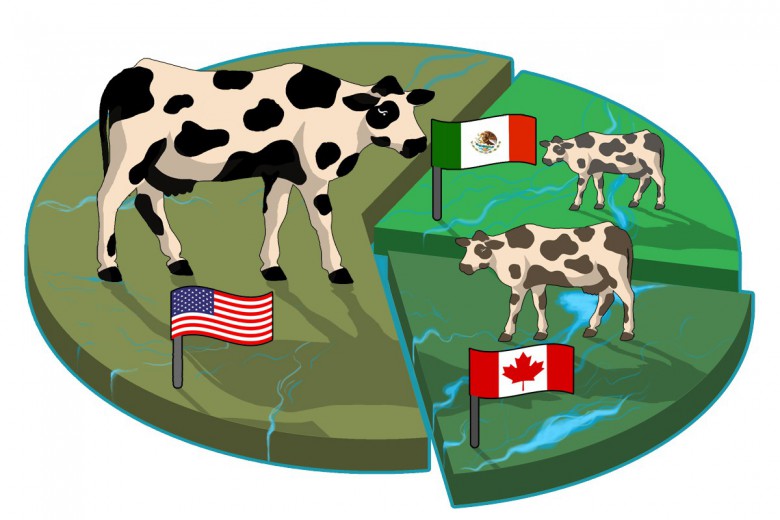

O’Shea cites Wal-Mart as the biggest threat to Canadian farmers. The current industrial food system – characterized by large grocery store chains flooded with cheap American and Mexican produce, grown under lax or absent labour and environmental legislation, and corporate control over seeds and fertilizers by agribusinesses like Monsanto – threatens the autonomy of small-scale Canadian farmers and puts them at a severe economic disadvantage.

In this context, small-scale farmers like O’Shea need the support of urban communities in order to survive, and agri-tourism offers them not only a means to supplement their farming income but also to influence the politics of the urban public.

Part of the agri-tourist agenda is to highlight how small family farms like O’Shea’s respond to the critiques of mainstream agribusinesses. Visitors learn how small yet conventional farms like O’Shea’s are deeply committed to soil, air and animal care. Here the strawberries are grown on raised beds and sheets of plastic, allowing the O’Sheas to avoid using pesticides and fungicides. Unlike factory farms, the pigs are bedded down in straw rather than on concrete slats. Visitors also learn that farms are part of broader community ecologies. For example, bees from a local beekeeper are housed at O’Shea’s to pollinate their plants. The farm uses minimal chemicals and employs fairly compensated labour. All of these qualities are, paradoxically, the same factors which make local produce less competitive in local grocery stores.

‘You could call it education, or you could call it marketing’

Agri-tourist destinations are nodes in a more complex infrastructure of initiatives that promote and educate the public about local agriculture. Farmers’ markets, agricultural museums (like the Canada Agriculture Museum in Ottawa) and the classic fall fair have all historically offered non-farm folk opportunities to learn from farmers about farming. What is distinct about agri-tourist destinations is that visitors are afforded the opportunity to understand food production in situ – not just the prize show heifers but actual supper in the making.

At O’Shea’s Farm, school programs operate all school year. Developed to correspond with the school curriculum, the programs introduce children to the care and importance of farm animals. Students are introduced to various species of trees in the forest and they play a grocery bag game to learn about where their meals come from. In the spring, children on class trips plant pumpkin seeds and are given Junior Farmer certificates that they can redeem in the fall for a full-grown pumpkin.

Visiting O’Shea’s Farm is unquestionably a fun experience. Children love all of the attractions and seeing the protagonists of their favourite barnyard storybooks alive and well and chewing their cuds. Meanwhile, their parents and other adult visitors can be assured of food production practices that subvert dominant agribusiness models.

O’Shea has a pragmatic approach toward the educational elements of his farming business: “You could call it education, or you could call it marketing.” Educating children about local food is one key way to sustain local agriculture. Agri-tourist attractions like this farm are attempting to make the significance of buying local produce very clear.

Farmers have intensely reverent relationships with their land. Farmers do slow down and admire fields: their fields, their neighbours’ fields, beautifully abundant fields and tragically frostbitten fields. It’s called crop touring, and it is good Friday night fun. Agri-tourism allows farmers to share their appreciation of agriculture, at least for an hour or two, with non-rural folk. With the lack of awareness about the logistics of food production bringing detrimental consequences for local farmers, agri-tourism ventures have become an important means of marketing local food. Alongside farmers’ markets, community-supported agriculture and other local food movements, agri-tourism is part of a response to the environmentally and socially devastating globalization of food production.