Picture a man in his late 40s, balding, bent over the telephone, the sun falling in slats across his sagging skin. Wisps of salt and pepper hair, unevenly cut but neatly combed, curl over his faded collar. He is staring past the kitchen counter, across an ocean only he can see. His hands rest on the chipped Formica, cupping empty air, still as dead birds.

The man has been awake since long before first light. He has taken his wife to work, packed lunch for the kids, guided them through morning prayer, and dropped them off at school. He has washed the dishes and put them away, folded the laundry, and made a list of household items in short supply. If by chance his gaze drifts over his fingers, he will feel tiny threads strain almost to breaking in his heart. It’s been years, and he wonders if his fingers still know how to cradle, to measure, to carve.

But such questions are worse than silence, so he will cast them into exile, again and again. There seems nothing to his body but the fickle allegiance of shadows. There is nothing now but the wait.

For seven years after our family emigrated from Indonesia to Canada, my father could not find employment. A dentist with two decades of experience, he failed the recertification exam due to language barriers, yet was deemed overqualified for menial entry-level positions. My father never stopped working – cleaning, washing, cooking, shopping for the family – and he even organized the few and scattered Indonesians we knew to found a new church. Yet in those years, before he passed away from cancer, I watched him unravel day in and day out on the edge of an abyss. He was a serious man of faith; he never smoked or drank away the pain. Instead it lived and took root in him, becoming his language and his most refined weapon.

As the oldest child, at age 10, the responsibility of writing my father’s resumés fell on me. Subsequently, I bore most of the brunt of his frustration and despair in the form of perpetual verbal violence. This period of my childhood and young adult life was dominated by feelings of entrapment, abandonment, humiliation, and powerlessness, magnified because they were not only mine but my father’s as well, a personal hell which continued to engulf me for years. Perhaps it’s no surprise, then, that in university I chose to specialize in political economy. Looking back, I think I was trying to understand how it was that human beings could lose their value. I wanted to be able to take the system that had victimized my father and smash it to pieces. And I needed, above all, a reason to forgive him.

Expanding cycles

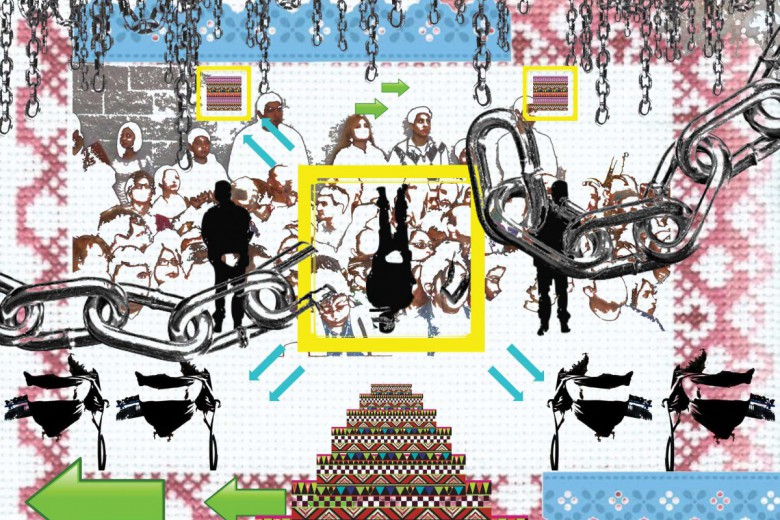

Capitalism was born when, through land appropriation, colonization, and slavery, a small group of people gained control over the majority of humanity’s means of survival. In so doing, they created a new relationship to organize the generation and fulfilment of human needs and desires, a mutual though extremely unequal dependence between the owning and working classes. The former came to control the means of production (land and factories) and the latter were forced to sell their labour in order to purchase the goods needed to live, which are simultaneously the alienated fruits of their own labour. This exchange is facilitated by an abstract value system – that is, money – imposed by the owning class to allow them to buy and sell disparate goods on a large scale.

In a barter system, a stack of firewood is worth whatever you might have to offer that is equally needed by the wood chopper. In a capitalist system, a stack of firewood is worth a certain amount of money relative to demand. The owning class applies the same principle to labour. The owner must keep the cost of labour low enough to be able to mark up and sell the finished good at profit, meaning retrieve all his costs and then some. Generally this means offering the good to consumers at a price and quality comparable to his competitors (or artificially raising consumer demand through brand advertising). The profit is then reinvested in ever-expanding cycles of accumulation: acquire more land, resources, and labour in order to make more stuff, sell more products, and generate more profit.

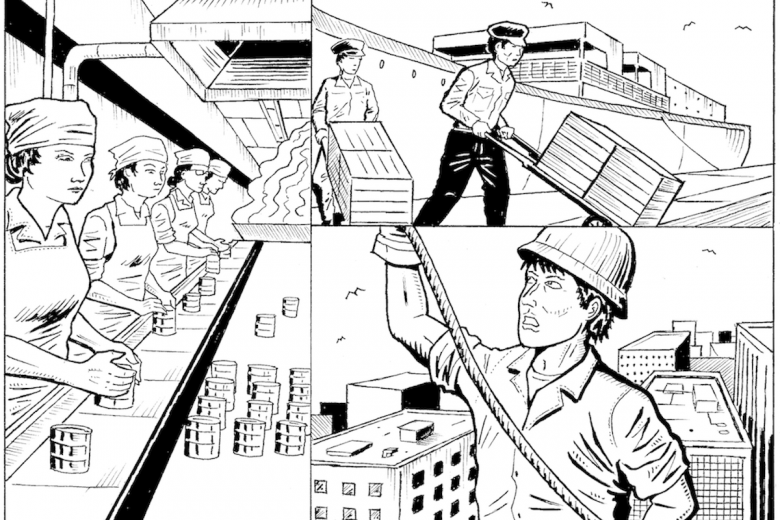

Unemployment is not an accidental byproduct. It generates a pool of desperate people that makes those with jobs more anxious about losing them and both groups more willing to settle for dismal wages. Particularly during a recession, it helps ensure the continuity of profit. However, labour value is also determined by other systems of social stratification. For instance, my mother, having been a housewife for over a decade, trained as a nurse in a so-called Third World country, and commanding very little English, became desirable as cheap labour to factory owners in the so-called First World who saw Southeast Asian immigrant women as docile, obedient, and unlikely to organize for their rights.

Worthy lives

This analysis helped me to locate my family’s experience within a bigger picture, but it could not repair the damage that had been done. The trauma resulting from my father’s unemployment goaded me into becoming a workaholic as an adult, and the fact that I was a young and broke single mother only made my addiction seem more justified. I understood that I was being exploited, but here is where armchair revolutionaries miss the point when they accuse workers of having false consciousness: feeling exploited, for many people, is preferable to feeling worthless. Very few of us have had lives that affirm our intrinsic value as human beings. More often than not, especially as women, people of colour, and immigrants, what we hear about ourselves is that we are stupid, wrong, weak, ugly, and undeserving. In Canada, I saw dogs in the neighbourhood around my elementary school that were better fed than I was.

Fast-forward a decade from my university studies, and I am in New Jersey, an immigrant again, and unemployed for the first time since I was 15. A few of my closest friends – very smart, talented, and experienced women – have also been seeking employment for months. Some of us struggle for enough to eat. Some of us stay in harmful relationships so our kids will have a roof over their heads. Some of us live in buildings that are falling down because we have nowhere else to go. Everyone is in a different position, but everyone is asking the same question: “What am I worth?” Words like “recession” do not provide an answer. We feel like we are wading through someone else’s nightmare; we feel weightless and heavy at the same time, a burden on those we love. Some days we feel like we cannot breathe, like we are treading water, our lives like a huge ship sinking below us as our bodies fill with bile and our hearts threaten to give out. We are afraid to hope; we are afraid to trust. We are afraid.

Lately, I’ve been considering what it means to shed my illusions. When I had a job, I could have all the radical politics I wanted without ever having to feel what my father felt in that kitchen, day after day, when everyone had left. Working in the non-profit industrial complex, I was getting paid to be outraged. I could move in and out of “empathy,” run a workshop, or throw out a lifeline without actually experiencing what it was like to be so close to drowning. I could pass out from exhaustion every night believing that I had earned my kid’s breakfast the next morning. Even now, I look at my hands and know that I can write, that someone will read my words. But illusion gets us only so far in our struggle for liberation.

Unmoored from the system, going for months without its recognition – that is, the value of a paycheque which reveals itself only when we have been cast (or kept) out – I sincerely wonder: Are we ready to unearth what we are truly made of? To resist the demons we have carried on our backs that would have us believe we are worth only what is in our bank accounts or what we can put on the table for our families? To confront ourselves without our illusory alter egos, our abstract values, the labels we have been assigned by a system which has thrived upon the theft of our lands, heritages, blood, and sweat? I don’t know. What I do know is that unemployment has shown me just how thoroughly and perfectly a subject of capital I am.

As we truly are

A theory of labour has been of limited use as an intervention in the way I name my predicament to others and myself. It would be a huge mistake, for one, to conflate labour – the commodified version of our time, energy, and skill – with work. I don’t know a single unemployed person who is not working as hard, if not harder, than they used to when they had jobs. In this limbo, there is no punching in and out. There is no one to quantify our performance and give us either a promotion or a warning slip. There is no one to punish us and no one to save us. There is only us, constrained by lack of autonomy and resources, distilled to our capacity to create what we need. “Be poor like that – as we truly are,” wrote the poet Rainer Maria Rilke. We must find a way to dwell in the eye of a needle.

To those readers going through a similar experience, I have no solution to offer, only these words to let you know that you are not alone. We are at the front lines of the fight for a just and humane world where everyone has the capacity to live with dignity, even if much of the time we feel like scattered bits of collateral damage. Paul Celan once wrote, “I hear that they call life our only refuge.” For some reason, this comforts me, to know there is no escape, that cowardice is not even an option. All we have are our words, our actions, and our intentions – the tenuous bonds that we sever or forge with each other.