On June 30, 2012, Citizenship and Immigration Canada (CIC) implemented cuts to the Interim Federal Health Program (IFHP), severely curtailing access to health-care services for refugee claimants and refugees. Many beneficiaries and practitioners were already critical of the original IFHP because it provided inconsistent access to health care and many services were not covered. The situation only worsened after the cuts.

Health-care coverage for medications, basic dental and vision care, and rehabilitation services was no longer available to any migrant in Canada previously covered by the IFHP. One uniform level of coverage was replaced by different levels of coverage based on immigration status and country of origin. Figuring out who was eligible for what services became a nightmare for even the most experienced health-care providers working with refugee populations across the country.

Loly Rico, a Salvadoran refugee who co-founded Toronto’s FCJ Refugee Centre in 1991, ran a clinic for the uninsured after the cuts. She noted that many of those who came had been turned away by institutions that couldn’t be bothered with filing complex paperwork for payment.

The Scarborough Volunteer Clinic for Medically Uninsured Immigrants and Refugees was seeing three to four times its usual volume within months of the cuts. Jennifer D’Andrade, lead nurse at the clinic, observed that migrants with chronic conditions had run out of medications. “Not only do we have an increased workload, people coming in now are definitely sicker,” she told the Toronto Star.

Children were not exempt from the IFHP cuts. Last year the Globe and Mail reported that Veronika, an adolescent Roma refugee claimant from Croatia, went to the emergency room because of profuse vomiting in the context of a flu-like illness. The visit ultimately cost hundreds of dollars, not easily affordable for her struggling family of six.

Veronika didn’t have access to publicly funded health-care coverage because Croatia is a “Designated Country of Origin” (DCO), deemed “safe” by the Canadian government despite violence and prejudice against the Roma population. According to Amnesty International’s annual report for Croatia in 2013, “Roma continued to face discrimination in access to economic and social rights, including education, employment and housing.” The IFHP cuts linked health-care policy to the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act, which was amended to adopt the concept of DCOs through Acts of Parliament in 2010 and 2012. Refugee claimants like Veronika, coming from DCO countries, became ineligible for health-care coverage unless they posed a threat to public health or safety.

Because the IFHP cuts were implemented through an Order in Council, there was no parliamentary debate. Health-care workers responded by mobilizing resources to provide health care for more uninsured migrants in birthing centres, clinics, and hospitals. The response also involved actively protesting the cuts by disrupting Conservative MP events, and staging office occupations and public demonstrations. Many of these actions were spearheaded by Canadian Doctors for Refugee Care (CDRC), a network of practitioners involved in providing health care to refugees.

In July 2012, the Montreal-based Health Justice Collective (HJC) initiated the “We Refuse to Cooperate!” campaign to encourage health-care providers across the country to defy the IFHP cuts by providing health care regardless of immigration status. One of the HJC’s goals was to underline the links between immigration legislation and health-care policy.

In 2013, Hanif Ayubi and Daniel Garcia Rodrigues, two people directly impacted by the IFHP cuts and supported by the CDRC and the Canadian Association of Refugee Lawyers (CARL), initiated legal proceedings against the Canadian government to reverse the cuts. On July 4, 2014, the Federal Court issued a scathing judgment, deeming the cuts to be “cruel and unusual” treatment as set out in section 12 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. The court gave the federal government four months to comply with the decision. The government has since issued amendments that soften the brutality of the initial cuts, but IFHP beneficiaries are still worse off than before the cuts were implemented, and confusion persists about who is eligible for which services. Not surprisingly, the Conservative government has appealed the Federal Court decision.

The IFHP cuts were the latest example in the long history of unjust treatment and contempt reserved for migrants by successive Canadian governments. They were a tip-of-the-iceberg phenomenon, offering a glimpse into the reality of tens, if not hundreds, of thousands of people who lack health-care coverage because of precarious immigration status.

The fact that some people are able to access certain types of health care while others can’t, based on immigration status alone, compelled Paul Caulford, the founding medical director of the Scarborough Community Volunteer Health Clinic, to suggest that Canada has “an apartheid health-care system.”

Living underground

Migrants fall into one of several categories of health care coverage depending on their immigration status. Refugee claimants and other migrants may benefit from IFHP coverage depending on a variety of factors, but, even if they qualify for it, that coverage is itself variable.

Meanwhile, landed immigrants (i.e. permanent residents) in several provinces must obtain private insurance or pay out of pocket for health care services for the first three months or so following their arrival until they are eligible for provincial coverage. This legislated delay, referred to as the Délai de Carence (DDC) in Quebec, is also in effect in New Brunswick, Ontario, and B.C. Those who can’t afford private health insurance can only hope that they don’t get sick or injured during this period.

A child I treated during an overnight shift in the ER during my pediatric residency in 2007 wasn’t so lucky. Recently arrived from North Africa as a landed immigrant with his family, the child fell at the park and suffered a blunt abdominal trauma. The CT scan revealed that he had completely fractured one of his kidneys, requiring admission to the pediatric intensive care unit. His hospitalization lasted over a week and was to cost the family tens of thousands of dollars because he was weeks shy of eligibility for provincial coverage and his family couldn’t afford private insurance in the interim.

With the support of Project Genesis, a community organization that was coordinating a campaign against the DDC, the family publicly denounced the harrowing situation faced by landed immigrants because of government polices. A year after the injury, the family welcomed news that they wouldn’t have to pay the costs after all. Most individuals and families impacted by similar policies, however, do not have such fees waived or covered.

The stated justification for the DDC policy is cost saving, including by deterring Canadians from travelling to other provinces to receive free health care services not covered in their own provinces. However, a recent report by the Commission des droits de la personne et des droits de la jeunesse (CDPDJ) suggested that recently arrived migrants bore the brunt of the policy: of the more than 50,000 people affected by the DDC in Quebec in 2012, 85 per cent were non-citizens residing in the province, with the overwhelming majority being permanent residents.

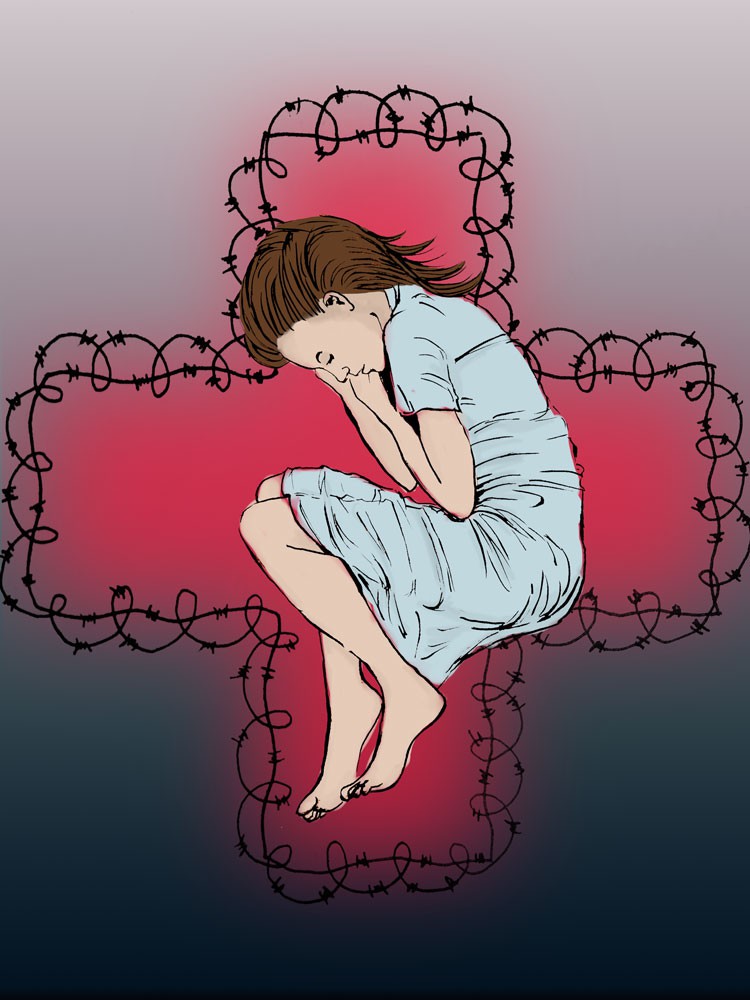

Finally, migrants forced to live underground because they have no immigration status – perhaps because of an overstayed visa or a refused refugee claim – are not entitled to access health care at all. They must rely on clinics for the uninsured, or on fragile, informal networks built by activists and sympathetic health-care providers. The sicker they are and the more dire their personal circumstances, the more challenging it becomes to provide appropriate and dignified care. Constantly under threat of detention and deportation, they face a revolting dilemma: delay seeking medical care or risk being picked up by the Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA).

Khurshid Begum Awan arrived in Montreal with her husband and grandson in 2011. The couple’s refugee claim was rejected in December 2012 and her husband was deported back to Pakistan in April 2013. Her application for a stay of removal was rejected and deportation proceedings against her were only delayed temporarily after she suffered a heart attack while in CBSA offices. Several weeks later, the CBSA sparked outrage when they attempted to detain Awan while she was in the hospital. Interventions by medical personnel, who argued that she was not fit to fly so soon after a heart attack, prevented the deportation temporarily. Ultimately, with the support of an ad hoc committee of migrant justice activists, Awan defied her deportation order and sought sanctuary in a church. The committee coordinated a group of volunteer physicians associated with Médecins du Monde (MdM) Canada to provide her with medical care during this time. Citing Awan’s case specifically, the president of MdM Canada publicly denounced the disastrous consequences of these immigration policies on people’s health.

In December 2014, Sanctuary Health, a health justice group in Vancouver, cited several examples of people staying away from emergency rooms for fear of the CBSA’s actions. Situations like these have compelled groups like Sanctuary Health, the Solidarity City Network in Toronto, and the Hamilton Sanctuary City Coalition to push for policies (“sanctuary city”, “solidarity city”, “don’t ask, don’t tell”, or “access without fear”) under which municipal governments would ignore immigration status for city residents accessing services. Such municipal policies may at times be only symbolic (health care, for example, is under provincial or federal jurisdiction), but these initiatives can nevertheless foster a culture that dissuades public service institutions from collaborating with the CBSA, which is an important step in ensuring safe access to health care.

Immigration policies that kill

In medical school, we now learn about the social determinants of health – how asbestos mining puts workers at risk for mesothelioma and how maternal education level is inversely proportional to infant mortality rates, for example. We learn less about the role of structural determinants of health: the systemic forces that frame people’s lived realities. We are certainly not taught how immigration policies may result in illness and death.

Precarious immigration status results in constant stress and worry about what will happen if one is injured, receives a life-altering diagnosis, or tries to ensure proper follow-up for ongoing medical care.

In December 2007, Quebec coroner Jacques Ramsay submitted a report outlining the deaths of four migrants with precarious immigration status.

One of these migrants, Monique Jean-Baptiste, was a 38-year-old Haitian woman living in Quebec without provincial health care coverage because she had an expired visa. Despite experiencing severe lower abdominal pain, she delayed calling emergency medical services. A friend eventually called 911 on her behalf, but the paramedics were unsure how to interpret Jean-Baptiste’s state, attributing it to anxiety related to a late menstrual period rather than physical pain. While being transferred to the ambulance, Jean-Baptiste went into circulatory shock and ultimately died in hospital. She had had a ruptured ectopic pregnancy, an almost universally fatal condition unless identified early on.

It is perhaps predictable that precarious immigration status impacts people’s ability to access dignified health care, but it should spark outrage when such status results in illness and death.

Beyond the obstacles in accessing health care due to immigration status, immigration policies that lead to detention and deportation have consequences on the health and well-being of migrants.

In 2013, almost 10,000 migrants were detained by the CBSA. That same year, a study published in the Canadian Journal of Psychiatry concluded that for “asylum seekers, even brief detention is associated with increased psychiatric symptoms.” The authors recommended that supervised residential facilities be used instead of prisons and detention centers. Meanwhile, the June 2014 report issued by the End Immigration Detention Network called for the abolition of immigration detention altogether.

If such calls had been heeded, Lucia Vega Jimenez might still be alive. Jimenez migrated here from Mexico and continued working precarious jobs after her refugee claim was rejected. In December 2013, she was stopped by Vancouver transit police for an unpaid fare and handed over to the CBSA after being racially profiled. While in detention and with the threat of deportation looming ominously, she attempted suicide by hanging herself with a shower curtain. She died of her injuries several days later in hospital.

Deportations themselves can also result in death. We have no reliable way to monitor what happens to those deported by the CBSA (including more than 15,000 people in 2013 alone). Many deportees are forcibly returned to places where their lives are threatened.

Migrants leave their homes amidst great difficulty to build new lives in a foreign land. Many are refugees of political, social, and economic violence, and can never return to their previous homes. In some cases, being sent back is a death sentence.”

Consider refugee claimants from Mexico, a DCO deemed safe like Croatia. Grise (whose last name is not public) fled violence in Mexico and first arrived in Canada in 2004 with her mother and sister. According to the Toronto Star, her applications to obtain protection in Canada were rejected and she was ultimately deported back to Mexico in 2008. In June 2009, she was found murdered with blows to her body and a bullet in the forehead. A coroner’s report suggested that Grise had given birth about a month before she was killed, and the fate of the baby was unknown.

Such deaths are a direct result of Canadian immigration policy.

Health care for all … and status for all

As groups like No One Is Illegal have highlighted, Canada is active or complicit in producing conditions that result in displacement and forced migration on one hand, while preventing immigration of the displaced to Canada on the other. This hypocrisy is all the more stark considering Canada’s foundation in violent land theft and the genocide of Indigenous peoples. The Canadian government’s attempts to dictate who can come to live on this land extend from the injustices that underpin Canada’s existence as a settler state in the first place.

If we care about the health and well-being of those who migrate here, we must confront the systems that produce displacement and those that manage migration in a way that causes untold suffering and death. Once these systems are identified as fundamentally unjust and violent, it becomes possible to take positions – including against all detentions and deportations – that straddle both health justice and migrant justice, while supporting Indigenous struggles for self-determination.

The banners of “Health Care for All” and “Status for All” must be raised if we value the well-being and dignity of all.

This article has been adapted and abridged from an article first published in French in the Fall 2014 issue of Les Nouveaux Cahiers du Socialisme. The print version of this article in the March/April issue of Briarpatch contains several editorial errors that are not the fault of the writer. They have been corrected for online publication.