Ask my son what he wants to be when he grows up. Today, he’ll tell you he’s going to be a spy. Six months ago he was going to be a superhero. Ask my three-year-old daughter and she’ll tell you she wants to be a “sister-spy,” still looking up to her six-year-old brother and believing they will never be separated. As adults, we swoon over these answers and say, “Oh, you’ll make a great spy,” or we just melt over my daughter’s cute naiveté. At a certain age we all believe the future holds limitless possibilities.

I remember answering the “when you grow up” question. Nine or 10 years old, with a few years of community soccer under my cleats, “I wanna be a soccer player,” I said. “Oh, that sounds awesome,” said my teacher, but she fiddled with her chalk a bit, then said, “But there aren’t actually many people who make a living playing soccer.” I was upset about giving the wrong answer, but I also remember being determined to prove her wrong. I still believed my future to be limitless, even if she was less hopeful.

Eventually, though, a person reaches high school, where there are more important things than soccer, and teachers make you take aptitude tests that tell you where to work – as a lumberjack or a janitor or a king crab fisher, a doctor, a lawyer, whatever else – and the world starts asking you, instead of what you would like to be, what you are planning to do with your life, which really means: “How are you going to make money?”

As a university student, I worked as an English tutor and writing instructor. Today, I work as an English and social studies teacher at an adult learning facility. Before that, I worked as a youth care worker at a group home, where part of my responsibilities included helping teenagers with homework. I’ve been studying and helping others with their studying all my life, and the most common complaint I hear among those frustrated with learning is: “Why do I have to learn this? I’m never gonna use it in the real world.” I’ve heard it from 14-year-olds studying the Confederation of Canada, from university students writing essays in English 101, from adults learning comma usage for their GED essays, even from arts-education students in an aesthetics class (and I might remember expressing the sentiment myself once upon a time learning algebra).

But what are we talking about when we say “the real world”? Inevitably, we mean the career we see ourselves in once we’ve finished this pesky task of learning. That is to say: the moment one has answered the question “What are you going to do?” in a society that equates that question with making money, it becomes hard to value learning anything outside of one’s career path.

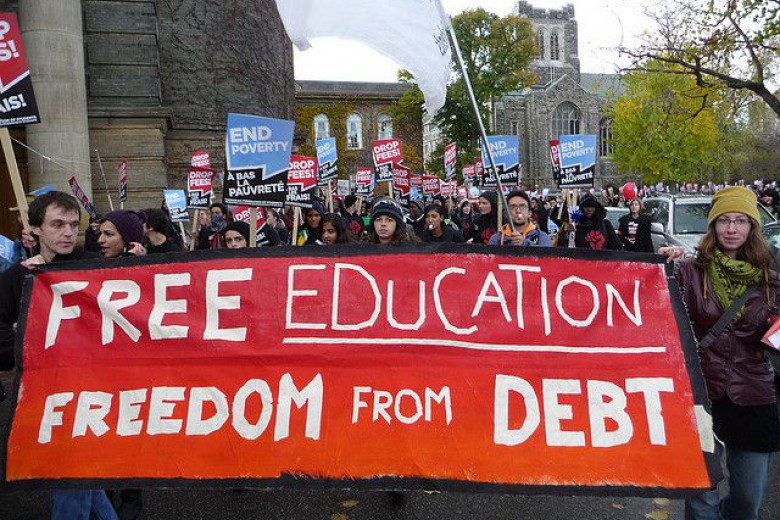

Anyone within earshot of a university will hear one student or another talking about BS’ing their way through essays, midterms, or even finals. “Four years of busting my ass just so I can hang a piece of paper on the wall,” goes one refrain. “You need a degree to make money these days,” goes another. I think of those arts-education students – who will eventually be charged with teaching our children to create art – questioning if they should think about why something is considered beautiful. What student doesn’t have that hard-working but skeptical uncle whose advice is always, “Just figure out what your prof wants and spit that back to him on the exam”? We have turned earning a degree into “an investment,” and that mindset has trickled down to our high schools and elementary schools, where a teacher feels she needs to tell kids they can’t make money playing soccer.

We ought to be asking students – of all ages – not what they want to be, but how they want to be when they grow up. One can answer either question a hundred ways, but where high-school kids can’t say, “superhero” (the what), they can answer, “brave and adventurous and courageous” (the how). They can’t say, “sister-spy,” but they can say, “I want to be close to the ones I love.” They can say happy, free, healthy, energetic, funny, safe, secure, whatever. Each question leads to the same follow-up of “What are you going to do?” but each has an entirely different motivation behind the question. “What are you going to do to be happy?” vs. “What are you going to do to make money?”