To hear Saskatchewan’s agriculture minister tell it, it’s all about the cows.

Announcing the end of the Saskatchewan Pastures Program (SPP) just five years short of its hundredth anniversary, Minister of Agriculture Lyle Stewart says, “Managing private cattle is no longer a core business function of the government.”

The decision was one of several major program cuts announced in March with Saskatchewan’s 2017 budget. But this cut was not about implementing austerity. A backgrounder to the government press release says, “There are no budget savings at this time from the transformational change decision to end the SPP.”

Still, the government’s timing and tone implies its intent is to stop wasting resources on an outdated program, and let ranchers look after their own cows.

Trouble is, a pasture is not a herd of cows. It’s the place where they graze – a place that requires care and attention to sustain it. The pastures in the SPP include 780,000 acres of land in 50 places across the province, from the Dixon and Mankota pastures flanking the Grasslands National Park at the U.S. border to the Smoky Burn Pasture on the edge of the northern forest east of Prince Albert. They’re community pastures, meaning they host mixed herds of cattle from multiple owners in the surrounding areas. Each of these 50 pastures has a name and staff with local wisdom about the land, and a yearly community gathering at the fall roundup where pasture patrons help sort out their own cattle to go home for the winter.

More than just grass

These pastures are not just any land. According to an influential 2001 report by the Native Plant Society of Saskatchewan, nearly 80 per cent of the grassland within these pastures is “native dominated,” meaning it hasn’t been plowed up and seeded to a simplified mixture of non-native plants. Instead, the cattle eat the same types of plants that the bison grazed before colonization.

Grassland grows much more than just grass. When Eric Lamb takes his plant sciences students out to the Kernen Prairie on the University of Saskatchewan’s crop research farm in northeast Saskatoon, they are amazed to see so many species in one place, he says. Numerous grasses and grass-like sedges coexist in prairie. Hundreds of other plants add value, such as low shrubs sheltering small birds, or legumes (pea-family plants) hosting rhizobium bacteria – nature’s nitrogen-fertilizer factories.

With diverse species thriving under different conditions, prairie can continue to produce through wet years and droughts. As climate change brings wider swings in weather, prairie may become crucial to carry cattle producers and their communities through the extremes.

Not only that, but prairie can help resist climate change itself. Deep-rooted grassland plants store carbon underground, safe from the wildfires that release carbon from forests.

It’s easy to overlook the contribution prairie makes to biodiversity. To a prairie dweller, a forest can seem like an oasis hosting an abundance of life. But prairie hosts a different kind of richness: grassland specialist species found nowhere else.

Hidden mandates

Announcing the pasture program cut, Minister Stewart mentioned the need for “continued environmental stewardship.” As background to the government’s online survey about the pastures’ future, a “pastures education document” outlined measures to identify and protect “ecologically sensitive lands.”

But none of this acknowledged any ecological role for the pastures program itself. The consultations were not to address the program cut itself, but only the future of the “affected pasture land.”

Consultations with First Nations and Métis communities were limited to next steps, rather than the use of the land more generally. As Crown land on Treaties 4 and 6, the pastures offer some protection of traditional territories, and could also offer opportunities to fulfill the Treaty Land Entitlement framework – land debts left outstanding since the treaties were signed.

But this government didn’t want to discuss the pasture program and any functions it may have acquired since its inception.

Pastures as Prairie conservation

In 2012, the conservative Saskatchewan Party government decided not to take over the care of another 62 community pastures from a similar system cancelled by the federal government. That system, formed in the 1930s under the Prairie Farm Rehabilitation Administration (PFRA), always had an explicit conservation mandate, starting with soil protection.

As climate change brings wider swings in weather, prairie may become crucial to carry cattle producers and their communities through the extremes.

But over the decades, both pasture programs evolved, quietly becoming the second- and third-largest conservation programs (by area) for native grasslands in Saskatchewan.

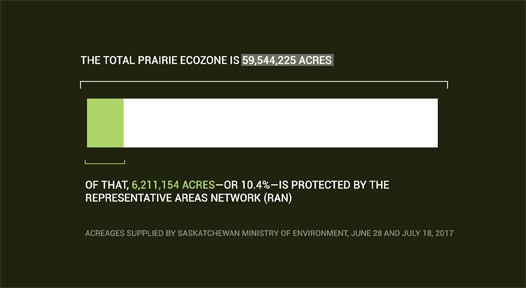

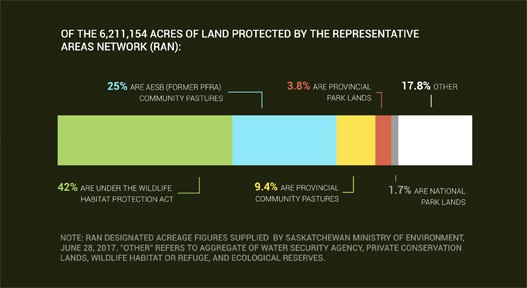

You wouldn’t know it from the agriculture ministry’s statements, but both sets of pastures are formally designated in Saskatchewan’s Representative Areas Network (RAN) as ecologically important land. The provincial pastures make up 9.4 per cent of the land the province reports as “protected areas” outside the forests of the North, and the PFRA pastures constitute another 25 per cent.

And now both programs are on their way out.

A pretend program

The RAN is Saskatchewan’s contribution to Canada’s conservation efforts under the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity. Established in 1997, the network of protected areas is still short of its 12 per cent land area target set in 1992. Meanwhile international targets have moved higher, to 17 per cent.

And yet the current government is giving up its direct management of one-third of what little grassland it has protected, without discussing the impact on the RAN. It has even proposed selling some of the land, underscoring the weakness of the RAN. Rob Wright, a former government scientist who spent 15 years in Saskatchewan’s forest services and 10 years in parks, said of the RAN, “It’s a pretend program.”

The current government is giving up its direct management of one-third of what little grassland it has protected.

The official story from the environment ministry is that nothing has substantively changed. In an emailed response to my request for an interview, a representative said, “The federal transitioned (PFRA) community pastures and provincial community pastures make an important contribution to the Representative Areas Network (RAN) and although the community pasture programs are being discontinued these lands will continue to be recognized in the RAN.”

It’s a bold non-move, but perhaps not surprising given the position the ministry is in. Without the community pasture lands to boost the RAN’s numbers, there would be no way to disguise Saskatchewan’s failure to protect prairie.

Protection that isn’t

In a 2005 report – the most recent update available on the province’s RAN website as of this writing – Saskatchewan’s Ministry of Environment acknowledged it had a problem finding land to protect. One of its two grassland ecoregions was already 80 per cent cultivated, and less than six per cent was protected. And that’s while using a very loose definition of “protection.”

When the PFRA land was added to the RAN in 1998, Wright says he argued, “The pastures should not be in the RAN. They’re not protected; they can be withdrawn. It’s just policy.” But the province designated the land anyway, and further added its own pasture system as part of the RAN in 2002.

In 2012, a federal omnibus bill confirmed that even the venerable PFRA would be cut, returning the land to provincial management. By this time, the Saskatchewan Party was in power. Passing up the opportunity to absorb the PFRA system and reinvigorate its own community pasture program, the province said it would lease or possibly even sell the land under “no break, no drain conservation easements.” Thus we learned what the current government considers adequate protection for prairie: a restriction on the land title saying, basically, you mayn’t plow it up or drain its wetlands.

After public outcry, the province withdrew the proposal to sell and said each pasture’s patrons would have to form a business unit and lease the land.

Now, touting the still-in-progress PFRA transition as a model, the province is terminating its own pasture system. The government even suggested again that some land could be sold.

But in the consultation process, respondents to an online survey made their objections clear. Nearly 60 per cent opposed selling the land. Three-quarters said ecological preservation should come ahead of economic opportunities, rather than both being equally important. The survey did not offer an option to continue the existing pasture program, but many respondents used the comment boxes to ask for this.

After public outcry, the province withdrew the proposal to sell and said each pasture’s patrons would have to form a business unit and lease the land.

With the release of the survey results in June, the province said it would roll the community pastures into its existing grazing lease program, where land is managed by individual ranchers, grazing co-operatives, and now the patrons’ new business units.

In the grazing lease program, pasture land will have the protection of the Wildlife Habitat Protection Act (WHPA). Like the Conservation Easements Act, this law prohibits “alteration” (such as plowing) of habitat. And, following amendments to both acts in 2010, some WHPA land can be sold.

There is already a lot of land designated under WHPA – enough to make it the largest category of conservation land in Saskatchewan’s prairie region, larger than both pasture programs combined. And WHPA land is also part of the RAN.

If the remaining pasture transitions go ahead, Saskatchewan will be relying on Crown agricultural land under WHPA to account for over 75 per cent of its protected grasslands. And it will be expecting all this protection to happen without the resources of the former pasture programs, including the ecological specialists providing oversight on the leased lands. In the lease program, protection is complaint driven, activating only after significant damage is done.

What prairie needs

Land protection takes more than legal designations. By dismissing the need for public management, the Saskatchewan Party government is treating “ecological value” as if it were a static, fixed thing, needing nothing from us except to keep the plows away.

Lamb says he often has to explain to people that prairie is “a human landscape,” shaped by people deliberately setting fires and shifting bison grazing for thousands of years. At the Kernen Prairie, he and his team graze cattle and burn small areas to mimic that process, creating patchy habitat where a greater variety of plants, birds, and other wildlife can meet their needs.

Prairie needs disturbance, and ranching offers that. Still, fenced-in cows are not a perfect substitute for free-roaming bison herds. Grazing patterns, intensity, and timing are all important, and extra measures may be needed to protect sensitive areas or control invasive plants introduced from Europe.

Ranchers want their land healthy to support livestock production. Many go to great lengths to protect the land they love. But federal management of the former PFRA pastures consistently promoted biodiversity. Anecdotally, many people have told me this is the healthiest prairie land remaining in the province. And in 2014, a researcher published definitive evidence of the PFRA’s achievement.

For her PhD study in southwest Saskatchewan, Allison Henderson compared pastures under private, provincial, and federal management. At 140 different sites, she and her assistants checked grassland health and counted songs of three grassland specialist bird species whose numbers are in decline. “You’re standing there listening to these birds, and in that moment it’s very clear how important these pastures are beyond livestock and beyond economic gains,” she said.

Henderson is now adjunct faculty with the University of Saskatchewan’s school of environment and sustainability. In an interview, she said private lands actually got better health scores overall than the provincial pastures. But unhealthy, overgrazed pastures, although rare, were always privately managed. And neither private nor provincial pastures were as healthy as the then-PFRA lands.

The well-resourced, biodiversity-oriented PFRA approach will be gone, leaving any variations in management approaches up to the choices of private ranchers.

Henderson observed that different management approaches produced a mosaic of different grass conditions, which supported different birds. In her thesis, she argues the variation in goals and grazing strategies has been beneficial, but should be created more consciously. She writes, “I advocate for a ‘mosaic by design’ rather than a ‘mosaic by default’ approach to native prairie management.”

Instead, we are moving from “mosaic by default” to “mosaic by accident.” The well-resourced, biodiversity-oriented PFRA approach will be gone, leaving any variations in management approaches up to the choices of private ranchers.

A simplified system

With its steady refrain that “ranchers are the best stewards,” the government has made its position clear: they won’t put money into pastures. The land and its ranchers should take care of themselves.

But all along, government has put large amounts of money into other aspects of agriculture, often driving conversion of grassland to crops. For example, in a 2017 research report, Branimir Gjetvaj anticipates a perverse effect if biofuel subsidies encourage new fibre crops that farmers can grow on marginal land they previously didn’t try to cultivate. All of these programs undo the carbon sequestration provided by deep-rooted prairie plants.

Gjetvaj said climate change may be driving some conversion as well, since a spell of wet years can tempt a farmer to break some more land. And then in dry years, that land may lie useless, since it takes decades to recover.

The community pasture systems were an exception, where government resources helped keep prairie intact and, in the case of the PFRA, outstandingly healthy. With so little prairie left, we urgently need strong protection, not just for its existence, but also for its health.

And that will need a public vision for the prairie that’s about more than just cows.