The power of Anishnaabe stories is rooted in our ancestral knowledge and thrives in the places from which we reclaim our power. Stories have helped to guide Anishnaabek since the days of our earliest fires. We share stories to remind us of our responsibilities, to instruct and entertain, and to remind us of danger, spiritual or otherwise.

Nanaboozhoo is an Anishnaabe protagonist of legendary proportions. Half human, half spirit, he is vividly alive through our stories and our continued acts of resurgence. His experiences as one of the first Anishnaabek on Turtle Island provide life lessons for us. His stories make us laugh, and sometimes they make us cry. But most often, Nanaboozhoo’s contradictions show us ways toward balance, truth, and power.

We also remember our stories about Windigo, monstrously tall and hideously lanky, hunched over from the weight of the rotten flesh hanging from the shadows of his bones. Windigo haunts Anishnaabek, feeding on fear, disconnection, and the lifeblood of the people.

In his 1995 book The Manitous: The Spiritual World of the Ojibway, Basil Johnston shares a story about Nanaboozhoo being trapped by Windigo. Hiding behind a grove of trees, Nanaboozhoo trembled and Windigo revelled in his fear. “The Weendigo had never experienced such pleasure before. It watched and listened as Nana’b’oozhoo quaked, wondering what people saw in him and how he could continue to assume the role of people’s champion,” writes Johnston.

A mouse was the only relative who had compassion for the sometimes boastful and foolish Nanaboozhoo. The mouse told Nanaboozhoo to find “a long, dry stave, hard and stiff with age, and thrust one end into the white-hot coals as a blacksmith does when he tempers metal.” While Windigo slept, Nanaboozhoo sank the stave into its stomach, awakening Windigo with a tremendous jolt and sending it running so far into the hills that it didn’t come back.

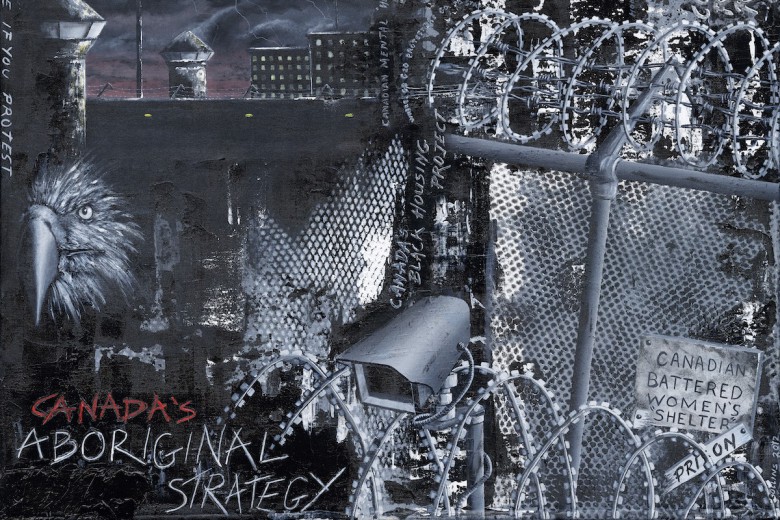

But Windigo is back. It never really left. It’s only that our stories have been interrupted by the theft of our languages, kinship, and fires. Windigo lives inside the black robes of residential schools, in the broken treaties, and behind genocidal institutions whose extractivist culture dominates Anishnaabek lives and lands. Upheld through racist policies like the Indian Act, Canada maintains space for Windigo to thrive and feed on the land, the water, and the people. Through stolen land and lives, Canada’s Windigo society has built its empire on a trail of death and destruction.

Windigo is back. It never really left. It’s only that our stories have been interrupted by the theft of our languages, kinship, and fires.

Nanaboozhoo defeated Windigo once, but only with the help of his fellow relations. We can tap into this power by living mino bimaadziwiin, the life-giving way of our ancestors. This is where we find our power: with the land and the water and living in accordance with our responsibility to protect life. Windigo is an intelligent design, not just a figurative illustration. And so we too must intelligently design the defeat of the Windigo spirit, so alive within Canada’s colonial violence. What better way to do so than on the anniversary of one of its official impositions on Indigenous lives?

This year, Canada celebrates 150 years of stolen land, broken treaties, and genocide. The ironic part is that Canadian society, blinded by greed and comfort, doesn’t realize that it’s stoking the fire meant for its own demise. How Windigo must be laughing.

Windigo society has become normalized through the colonization of minds, bodies, and relationships, in churches, governments, and corporations. Windigo wants to devour mino bimaadziwiin, the way of Nanaboozhoo and our ancestors. “The entire national culture becomes pervaded by myths, values and habits of action and thought conducive to the perpetuation of a [Windigo] society,” says Jack Forbes. Schools teach that settler colonialism is justified by a kind of manifest destiny, the opportunity for expansion made possible only by never-ending death.

At the height of his 2015 election campaign, Trudeau promised to allow First Nations veto over development projects like pipelines and resource extraction by implementing the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. He promised to increase funding for schools on First Nations reserves. He promised to implement all 94 calls to action of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission report. But instead of following through on those promises, he has approved Enbridge’s Line 3 replacement and the Kinder Morgan Trans Mountain expansion project. We receive apologies and promises while our waterways are poisoned and our women go missing. We shouldn’t be surprised by the lies, by the continued taunting, by our supposed rights held over our heads. It’s imperative that we acknowledge Windigo society for what it is and recognize the people who maintain it for who they are.

Where once Windigo was hideously terrifying, now it smiles, showing off its perfect teeth and glowing skin, which indicates the evolution and sophistication of the Windigo spirit. Johnston understood this transformation. “The Weendigoes did not die out or disappear; they have only been assimilated and reincarnated as corporations, conglomerates, and multinationals.” Political and corporate careers are dependent upon the expansion of this Windigo society, which requires the traumatic removal of Anishnaabek bodies from Anishnaabek land.

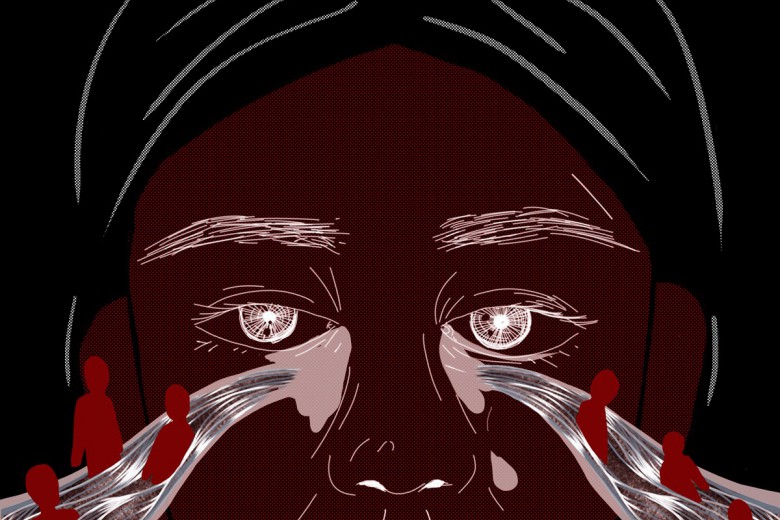

“Over the years, the Ojibwe experienced many traumas. That is the way of the Wiindigo,” storyteller Bezhigobinesikwe Elaine Fleming says in her retelling of relations between Nanaboozhoo and Windigo. Intergenerational trauma keeps Anishnaabek in a constant cycle of tragedy. Despite Canada’s promises to tell the truth and reconcile with Indigenous peoples, the cycle of tragedy continues.

As Mi’kmaq lawyer and activist Pam Palmater has pointed out, while Canada spends half a billion dollars on Canada 150, Indigenous communities face water, housing, and social crises. Almost a quarter of First Nation adults living on reserve are in over-crowded conditions as of 2013, and First Nations communities across the country, including in Attawapiskat, have declared suicide crises facing their young people in the past years. The narrative that patriotically characterizes Canada’s celebrations as honourable is the same one that silences ongoing violence against Indigenous peoples. How Windigo must be laughing.

Fleming warns, “Wiindigo wanders amongst our peoples, when we are weak and hungry.” By reclaiming mino bimaadziwiin, we can heal from past trauma and have enough strength to resist all that continues to harm Indigenous peoples and territory. We can confidently identify Canada’s 150th as a celebration of death, displacement, and cultural genocide. We can begin to reclaim our lives and our land by identifying the source of our trauma and our continued fears. Then we can begin to heal and live in the ways of our ancestors, in the ways of Nanaboozhoo, again.

“Nanaboozhoo represents our ancestors – those who gave us our rituals and ceremonies, our culture and language. These same things are what we are now, what we are picking up again,” says Fleming. Actively decolonizing our minds by relearning our languages and interrogating the Canadian narrative that lives in many of our hearts – n’mino bimaadziwiin – is one way to reclaim our power.

We are also a people of intergenerational power. Mino bimaadziwiin, instead. Grow your own food with heirloom seeds and then save the seeds and share that life with your neighbour. Sing your songs from the shorelines of the waters and live your ceremonies by re-creating loving relationships with yourself, others, the land, and water. Windigo has evolved; so we too must evolve.

We’ve battled Windigo for longer than 150 years. Mirroring Windigo society’s malevolent and gruesome truths with our art, our stories, and relationships is one way to expose Canada for what it is: a gruesome, cannibalistic design that, when coupled with capitalism, becomes the latest manifestation of Windigo. We are creatively exposing Canada’s true identity as Windigo. Through ceremony and kinship, we’re relighting our fires and creating stories once again.

We are also a people of intergenerational power. Mino bimaadziwiin, instead. Sing your songs from the shorelines of the waters and live your ceremonies.

We’re becoming the people that our descendants will tell stories about by living in our power once again.

It’s always been the places in which we’ve stood in ceremony, harmony, and balance that have ensured Anishnaabek survival. Nanaboozhoo lives in the small places inside all of us. We can all be champions of the people by living courageously, by exposing Canada’s intrepid Windigo design, by confronting Windigo and interrupting its narrative with our laughter, our love, our actions, and our nationhood.