A young man in his 20s broke the news to his friends while they were eating in a park in Srinagar. “Burhan is dead,” he whispered.

It was July 7, 2016. Over the preceding five years, 22-year-old Burhan Wani had become the face of militant opposition to the Indian occupation of the Himalayan region of Kashmir. Burhan was the commander of Hizbul Mujahideen, a pro-Pakistan Kashmiri separatist organization. He’d left home and taken up arms against Indian rule in 2010, at the age of 15.

“This must be fake news. He’s not dead,” his friends replied, shocked. But their denial receded quickly. “If Burhan is dead, how many more will be killed?”

In the next six months of protest, their question would be answered: around 100 people would die, and close to 15,000 would be injured.

The death of a militant

Burhan was shot by Indian security forces in the village of Bumdoora in a counter-insurgency military operation, along with two other militants. His rise to fame marked a new type of militant leader in Kashmir: the social media recruiter. He posted photos of himself surrounded by other militants, clad in camo and toting an assault rifle, his face boldly unmasked. His viral videos called for “freedom from Indian rule,” and openly condemned the police brutality and military occupation that mark life in Kashmir, encouraging other young people to take up arms against the Indian occupiers. Like much of the young generation of separatist militants, he came from a well-educated family – his father is a school principal.

“Burhan! Your blood will bring revolution. The more Burhans you kill the more will rise from every single household!”

Soon after the state police confirmed his death, a picture of his dead body went viral on social media. The streets of Kashmir erupted. Angry demonstrators burned tires and hurled rocks. The air filled with the smoke of thousands of canisters of tear gas and pepper spray. Security forces fired steel pellets, which embedded themselves in the skin and eyes of protesters, partially or fully blinding over 150 people.

Cries for “azaadi” – freedom – rang in the streets. Young men swung on the backs of trucks, shouting anti-India slogans. “Burhan! Tere khoon se inqelaab ayega. Tum kitnay Burhan maro gai ghar-ghar se Burhan niklay gaa! [Burhan! Your blood will bring revolution. The more Burhans you kill the more will rise from every single household!]”

Many of them began hurling stones at the nearby military bunkers that have mushroomed across the southern part of Kashmir. An estimated 700,000 soldiers, paramilitary, and police are stationed in the conflict-ridden state, making the area the most densely militarized place in the entire world.

Often it takes a single incident in Kashmir – the killing of a civilian by a paramilitary trooper, or a social issue like frequent power cuts, lack of drinking water, or crumbling roads – to spark months of protest and, in turn, violent repression.

However, in the summer of 2016, with the killing of Burhan, the state plunged further into crisis. What followed was six months of unrest – mass mourning and wailing, day and night demonstrations, and massive clashes between protesters and government forces. Authorities imposed 53 consecutive days of curfews. Schools were closed for months, and public transit halted. Hartals (strikes) continued for several months. The Srinagar-based newspaper Rising Kashmir compared it to the six-month general strike in Palestine against the British colonial government in 1936.

The politics of Kashmir

Since the partition of India and Pakistan in 1947, Kashmir has been claimed in its entirety by both countries. India administers around 45 per cent of the region, which makes up the Indian state of Jammu and Kashmir (J&K). The region has seen three decades of armed insurgency, with militants seeking to separate from India or merge with Pakistan. Today, there are a few hundred militants reportedly operating in the Indian-administered Kashmir Valley – though there were thousands during the height of the movement in the 1990s.

In the late 1980s, a series of rigged and fraudulent elections saw Kashmiri youth losing faith in the legitimacy of Kashmiri politicians. The two major political parties in Kashmir – the Jammu and Kashmir National Conference (JKNC), and the People’s Democratic Party (PDP) – are both pro-India and have, again and again, formed coalitions with India’s ruling parties.

In 1989, Kashmiris began to revolt against a visibly corrupt political system that continued to offer them a series of politicians sympathetic to their Indian occupiers. It was the start of a long and violent period of political unrest and militancy, which continued through the ’90s. The Valley flooded with Indian military and paramilitary forces, which remain to this day. There were no general elections held in Kashmir for seven years, between 1989 and 1996.

As of 2017, there have been at least 2,000 unmarked mass graves discovered in border areas of Kashmir, and human rights groups have accused government forces of staging gun battles to hide mass killings and “disappearances.” Women who are believed to be militant sympathizers are subject to sexual violence – like when Indian soldiers allegedly raped more than 30 women in the Kashmiri villages of Kunan and Poshpora in 1991. Militants, too, have been accused of kidnappings, sexual violence, and killing civilians.

Since the 1978 Public Safety Act, Indian security forces have enjoyed near-total impunity. The act allows government forces to “preventatively” detain people – including minors – who pose a threat to the state’s security. It’s often used to detain people who have not committed any criminal offence, and to delay the release of a person acquitted by a court.

Since 2015, J&K has been ruled by a coalition of the PDP and the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), India’s ruling right-wing Hindu-nationalist party led by Narendra Modi. The PDP and BJP’s relationship was always tense, worsened by differences in handling the renewed insurgency ignited by Burhan’s death. The BJP cracked down on separatists, while the PDP ordered the release of separatist leaders and granted amnesty to first-time stone-throwers. Then, in February 2018, BJP ministers publicly supported the alleged Hindu rapists of an eight-year-old Muslim girl in Jammu region, and the PDP’s leader, Mehbooba Mufti, forced the BJP to fire two of its ministers. The rift was out in the daylight. In June 2018, the BJP withdrew its support for the PDP, and Mufti resigned in protest. Her resignation led to governor’s rule being imposed, meaning that the BJP’s representative has since directly ruled the state.

As of 2017, there have been at least 2,000 unmarked mass graves discovered in border areas of Kashmir.

Then, in November, Mufti announced that she had the support of the JKNC and India’s National Congress party, which would allow the three parties to create a “grand alliance” and form government. Days later, J&K’s governor, Satya Pal Malik, dissolved the legislative assembly, which means a fresh round of elections are likely within the next six months.

As India’s general elections loom in April–May, the BJP has seen its public support dwindle. Many Kashmiris believe that the government has increased Indian military operations in order to escalate tensions in the Valley, with the aim of whipping up Hindu-nationalist fervour. Over 500 people were killed in 2018, the bloodiest year in Kashmir in a decade. Half of those were separatist fighters. “The body bags of Kashmiris sell in Indian elections, unfortunately,” Khurram Parvez, a human rights activist, explained to Al Jazeera.

The missing plebiscite

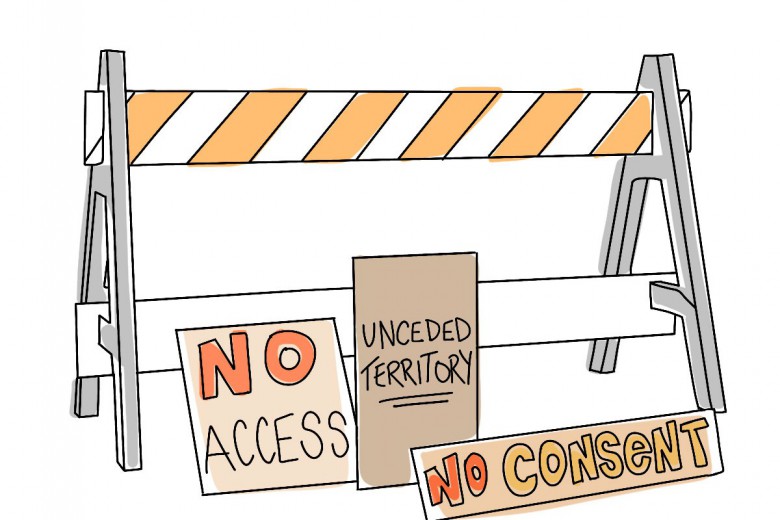

This year marks 71 years since the UN adopted Security Council Resolution 47. Recognizing India and Pakistan’s competing claims for Kashmir, the resolution recommended that India facilitate a plebiscite that would allow the people of J&K to decide whether the region would join India or Pakistan. And although India initially agreed to the plebiscite, it has since refused to hold the referendum.

Today, Kashmir is a patchwork of different regions with diverse populations: it’s assumed that the mostly Buddhist region of Ladakh in the east and the majority-Hindu population of Jammu in the southwest would vote to join India, while the majority-Muslim population of the Kashmir Valley in the south and of Pakistan-administered Azad Kashmir in the north would support allegiance to Pakistan.

But the proposed referendum never allowed for a third option, beyond joining India or Pakistan: an independent country.

Although Kashmir is a well-worn topic of jingoism in Indian media – so much so that most Indians and Pakistanis alike have lost interest in the occupation – Western media coverage of the occupation has been sparse. It’s largely because India’s reputation as a rising economic superpower, a liberal democracy, and a strong ally of the U.S. endears it to Western media. The Kashmiri people’s aspiration for freedom and self-determination has not sparked the kind of international attention or solidarity that, for example, Palestinian liberation struggles have received – despite the obvious parallels between the occupations.

Under Modi and Benjamin Netanyahu, India and Israel share a cozy relationship. In 2017, India – the world’s largest importer of arms – confirmed a deal to buy over $1.6 billion in missiles from Israel, making it one of Israel’s largest clients. Hundreds of Indian military and police forces have also been trained in Israel for counter-insurgency and “antiterror” operations, and Israeli-made drones are used in Kashmir to surveil mass protests and pinpoint the locations of militants.

The shared spectre of “Islamist terrorism” allows India and Israel to sanitize their brutal occupations.

In 2015, the BJP announced plans to resettle tens of thousands of Kashmiri Pandits – Hindus who fled during the insurgency of the ’90s – in new townships in Kashmir. The BJP is borrowing from Israel’s tactic of creating self-contained, heavily guarded settlements in occupied territory. Many Kashmiri Pandits opposed the government’s plan, worried they would become targets in Kashmir.

And there are similarities between the religious nationalisms of Hindutva and Zionism – both endear themselves to the West by posturing as neutral states fending off hostile Muslim neighbours. J&K is the only Indian state with a majority-Muslim population, similar to Palestine. The shared spectre of “Islamist terrorism” allows India and Israel to sanitize their brutal occupations.

Even when the occupation of Kashmir is discussed in Western media, it’s typically framed as a bilateral territorial conflict between India and Pakistan. And each time fighting breaks out in the Valley, the response from the two states is the same: India blames Pakistan for inciting the conflict, and Pakistan denies the accusation, saying that India instigated it. The fact that Pakistan has previously supplied arms, stationed proxies in the region, and recruited Kashmiri civilians into pro-Pakistan militias makes it easy for India to dismiss the azaadi movement as foreign-funded agitation rather than a legitimate struggle for freedom.

The reality on the ground is that the people who are fighting the hardest against Indian occupation aren’t necessarily fighting to join Pakistan. Though most of the largest militant groups are pro-Pakistan, there is a section of the younger generation who claim that Pakistan’s involvement in the conflict is informed by little more than self-interest. Fundamentally – as in Palestine – Kashmiris are fighting for an end to the violent occupation under which they live.

“A symbolic referendum”

When Burhan’s body reached his hometown of Dadasara in southern Kashmir on the morning of July 8, a sea of people turned out to attend his funeral. Defying a curfew, the gathering was estimated at 200,000 people. Teenagers perched on tree branches, and young men sat on tin roofs of houses to get a glimpse of the historic moment.

“The crowd of mourners was so dense and so immense that it took me an hour to walk a few kilometres,” says Shams Irfan, a journalist with Kashmir Life. According to Irfan, around 50,000 people packed inside Eidgah, an open-air prayer hall where Burhan’s funeral was held. After each round of funeral prayers, new mourners would fill the same ground again. They continued to gather for nearly a week.

“The funeral was a symbolic referendum in favor of [the] larger struggle for self-determination,” explained Zubair Ahmad, a scholar from Islamabad, who attended the funeral. “Referendum, otherwise, is a larger, informed democratic exercise – and this funeral was the best symbolic representation of what could happen if a referendum in Kashmir [took] place.”

The trend of funerals as political referendums in Kashmir dates back to at least October 2015, when the funeral of Abu Qasim, chief of the Pakistan-based militant group Lashkar-e-Taiba who was killed in a gunfight with police, saw a turnout of thousands of people.

“When my son left the family in 2010, I never expected that he [would] be able to garner such huge support,” 62-year-old Muzaffar Wani, Burhan’s father, told Briarpatch. “Hundreds of thousands showed up for his funeral, showing their support. My only concern, then, was [that] people should not get indulged in stone-throwing to nearby army barricades, as it would have inflicted more casualties and bloodshed.”

In its first report on human rights abuses in Kashmir, released last year, the UN concluded that Indian security forces had used “excessive force,” resulting in unlawful killings during crackdowns on protests in the summer of 2016, and called for an investigation.

“Recently, on his second death anniversary, many [asked] me how I feel,” says Muzaffar. “I told them that I have died every day, every moment, waiting in anticipation ever since he took up [a] gun, until his dead body was finally brought home wrapped in a shroud. For me, for my family, every day is an anniversary.”

Of guns and pens

In both life and death, Burhan sparked a resurgence in militancy in Kashmiri youth. Since his death, around 300 youth have joined militant groups. Police sources confirm that most of them have since been killed in different counter-insurgency operations.

“Militant killings anywhere trigger emotions across the Valley but in most cases, there is a strong correlation between the area of recruitment and number of militants killed from that area,” a 2018 report by police forces in J&K concluded. The report found that nearly half of all new recruits into militant ranks come from within 10 kilometres of the homes of slain militants.

One new militant was 26-year-old Mannan Wani, who was pursuing his PhD at Aligarh Muslim University, and joined Hizbul Mujahideen in 2018. Months after taking up arms, he penned two open letters in which he explains why he decided to join the militancy.

“Resistance is resistance; it can neither be peaceful nor violent. In fact, [the] violence is not that we have picked up gun[s] to fight occupation but violence is the presence of more than 12 lakh [1.2 million] Indian armed men in Kashmir, violence is the presence of fortified army garrisons, bunkers and pickets, and occupation in itself is [the] biggest violence,” he writes.

“I have died every day, every moment, waiting in anticipation ever since he took up [a] gun, until his dead body was finally brought home wrapped in a shroud.”

On October 11, 2018, during a gun battle that took place in Kupwara in northern Kashmir, Mannan was shot dead by security forces. But this time, when news of his death was announced, Indian authorities were already prepared to clamp down to prevent mass gatherings. The Internet was suspended in parts of north Kashmir, blocking the spread of information about Mannan’s death. Rumours circulated that other militants had been killed or had surrendered.

Police refused to confirm the news of Mannan’s death to reporters for hours. Journalists were barred from entering the village leading to his hometown of Takipora, which is heavily surrounded by military cantonments. Most of the reporters were asked to wait for hours, and hardly any photojournalists were allowed to cover the scene of the funeral prayers.

But despite the clampdowns, almost 50,000 people managed to attend his funeral. Mourners walked barefoot for dozens of kilometres from the neighbouring village of Palhalan to bid a final farewell to their hero.

“Mannan’s funeral could have been another symbolic referendum, given his popularity across the social classes, had the Indian state not done the kind of preventive management that it did,” says Latief, a law graduate from Tata Institute of Social Sciences, who requested that only her last name be used.

Amid a year of escalating political tensions, the Kashmiri diaspora living in Canada organized a silent protest in Toronto in August. The protesters carried placards with messages like “India, stop killing Kashmiris,” and “Justice not bullets.”

“The aim of [the] protest was to create awareness and remind [the] Indian state that they have promised [the] world community that they will conduct a plebiscite in Kashmir, which is yet to be held,” Womic Baba, who took part in the protest, tells Briarpatch.

Muzaffar Wani stresses, “Had killing been the solution, Kashmir should have been resolved by now. What will [the] state of India achieve [by] killing so many people here? Does their religion allow them [to] kill young men who are only seeking their dispute should be resolved?”

Without the promised referendum, street protests and mass funerals are one of the few remaining ways for the Kashmiri people to voice their desire for freedom. But as India’s general election looms, Indian forces will likely become more repressive toward public displays of resistance. Without uproar and condemnation from the international community, the Kashmiri people’s cries for azaadi will remain unheeded.