On June 18, 2012, the Harper government passed a 431-page omnibus budget bill. Buried in the text was a plan to scrap the Office of the Inspector General, one of two oversight bodies that scrutinizes Canada’s most prominent spy agency, the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS). Critics fear that without strong layers of oversight, CSIS will be left to operate in the shadows with vast abilities to abuse its powers and breach the public’s civil liberties.

Although the office will no longer exist, and its role of entering CSIS facilities to review records and monitor the agency’s compliance with law and policy will no longer be performed, a separate oversight body, the Security Intelligence Review Committee (SIRC), will continue to deal with public complaints and conduct reviews of selected elements of the service’s activities.

According to a Jean Paul Duval, spokes-person for the Department of Public Safety, the Security Intelligence Review Committee will take over and preserve the inspector general’s key functions.

“Consolidating review has eliminated the duplication that currently exists between SIRC and the inspector general, while ensuring that the review of CSIS activities remains as effective as it was before,” Duval told Briarpatch in an email, adding that “approximately $785,000 per year” would be saved by the inspector general’s elimination.

However, Paul Kennedy, chief legal counsel for CSIS between 1988 and 1994 and the former head of the Commission for Public Complaints Against the RCMP (the Mounties’ oversight body) from 2005 to 2009, spoke out publicly against cutting the inspector general before the budget bill was passed.

In a May 2012 op-ed on the website iPolitics, he wrote that the move was akin to the minister cutting off his “eyes and ears,” a term sometime used to describe the Office of the Inspector General.

Kennedy challenged the idea that last summer’s rewriting of the oversight laws was simply a matter of eliminating redundancy. He told Briarpatch: “Rather than being a combining of functions, there was a reduction, overall, of oversight of the intelligence agency. The powers that were transferred do not mirror the powers which were [previously] performed by the inspector general.”

Kennedy pointed out that the inspector general used to visit CSIS facilities and review records.

“SIRC doesn’t do that monitoring. It will do complaints and it will do strategic reviews but it isn’t monitoring the files the same way that the inspector general did,” explained Kennedy. “These things were complementary. They were designed as complementary tools.”

While the Security Intelligence Review Committee deals with public complaints against CSIS and conducts reviews of its activities on behalf of Parliament, the inspector general’s role had been to monitor CSIS to make sure it was acting in compliance with policy and the law. The office reported directly to the minister of public safety. This behind-the-scenes reporting was designed to ensure that any problems or potential scandals could be addressed without sensitive information being exposed to public scrutiny. Only a portion of the inspector general’s reports were ever made public.

The Security Intelligence Review Committee is composed of five members, political appointees who are often prominent business people and former politicians. By convention, it usually includes retired representatives from three of Canada’s major political parties: the Conservatives, the Liberals, and the NDP. Those appointed to fill the post of the inspector general, on the other hand, tended to be bureaucrats with national security experience.

Yavar Hameed, a lawyer who works on national security-related cases, considers the change “a loss.” He noted that so many of CSIS’s activities are secret that reports by oversight bodies are some of the only outside windows on the service’s activities.

For example, sections of a report from the Office of the Inspector General were useful in defending one of Hameed’s clients, Mohammed Mahjoub, who was detained for years without criminal charges. The allegations CSIS made against him were based on secret evidence that neither the public, Mahjoub, nor his lawyers ever saw.

Hameed told Briarpatch that the inspector general’s report “was one of the only tools that we had for going from the broad to the specific,” in a case where CSIS was allowed to not disclose any evidence it claimed compromised national security. “Through the court process, where we are only able to see the tip of the iceberg, we have to infer the stuff that’s not there.”

Both the Security Intelligence Review Committee and the Office of the Inspector General were created in 1984 with an eye to preventing the sort of scandalous activities that had plagued the precursor to CSIS: the RCMP’s security service.

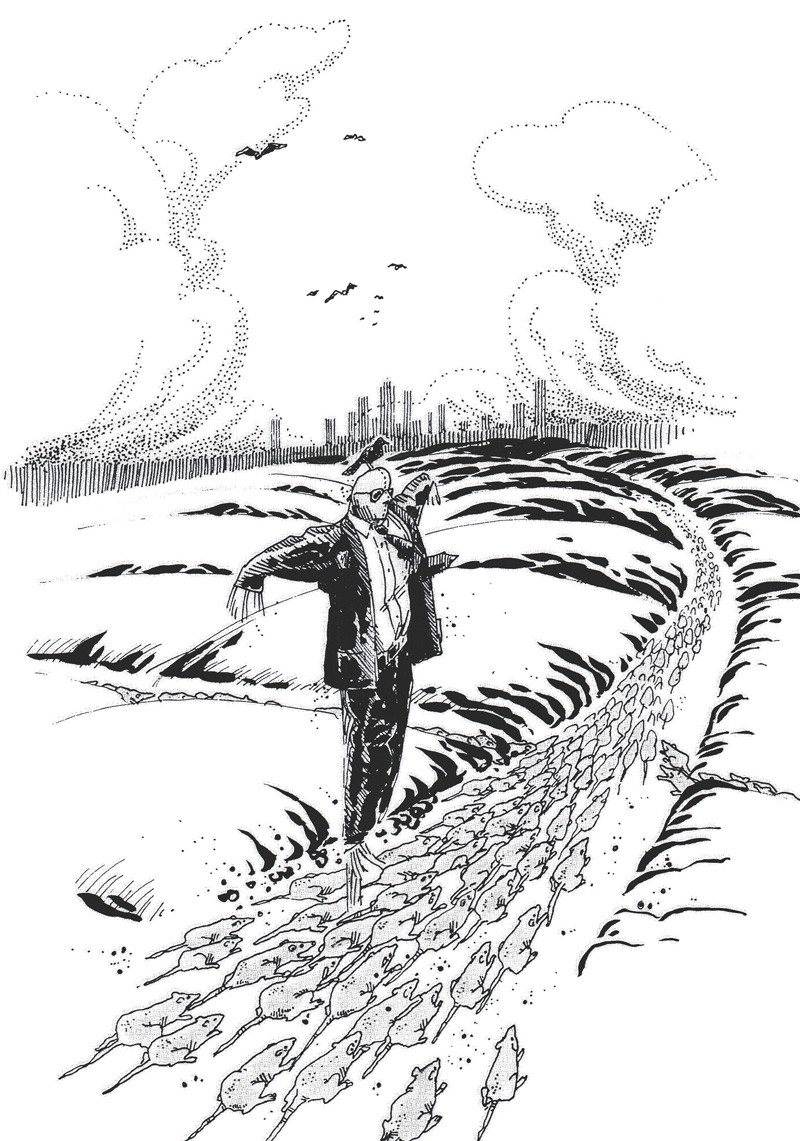

In the 1970s, journalists exposed numerous illegal activities undertaken by the Mounties to target leftist and separatist groups. These included breaking into the offices of political parties and organizations to steal records, using kidnapping and intimidation to recruit informants, writing communiqués purported to be from the FLQ (a militant Quebec separatist group) and reporting them as genuine, burning down a barn to prevent the FLQ from meeting with the Black Panther Party, and illegally obtaining people’s mail and personal records.

When the Parti Québécois, one of the targets of these tricks, won the Quebec provincial election in 1976, it called an inquiry into the RCMP’s activities. The federal government responded by calling its own inquiry, the Royal Commission of Inquiry into Certain Activities of the RCMP, headed by Justice David McDonald.

“The key recommendation that he came up with was that there ought to be separation between the RCMP and the intelligence function, and this ought to be put into a separate agency,” explained Kennedy.

McDonald’s reports recommended a civilian agency that worked inside strict rules and under multiple layers of oversight. His recommendations led to the creation of CSIS, the Security Intelligence Review Committee, and the Office of the Inspector General when the CSIS Act was passed in 1984. The latter two bodies were granted unrestricted access to most CSIS records, far stronger powers of access than other oversight bodies that scrutinize Canadian intelligence agencies and police forces.

Even with the recommended oversight, however, CSIS has not proven immune to abuses of power and the law.

The Bristow affair

“Spy Unmasked: CSIS Informant ‘Founding Father’ of white racist group,” read the headline of an August 14, 1994, article that appeared in the Toronto Sun. The rare exposé of CSIS’s controversial use of informants, and the ensuing scandal, raised serious question about the service’s political role and accountability under the law.

The article by reporter Bill Dunphy revealed that informant Grant Bristow was working for CSIS when he “helped create and direct” the Heritage Front, Canada’s leading neo-Nazi group. According to the article, he used CSIS funds to support the group’s activities, and he orchestrated its campaign to harass anti-racists.

A story by CBC’s The Fifth Estate later revealed that Heritage Front members, including Bristow, joined and attempted to subvert the Reform Party, then a fledgling mainstream political party to the right of the then-ruling Progressive Conservative Party. During the 1993 election campaign, Bristow and other Heritage Front members volunteered to provide security for the party’s leader, Preston Manning. The presence of neo-Nazis within the Reform party was exposed during the campaign – and may have cost the party votes.

When it came to light that Bristow was working for CSIS at this time, the Reform Party accused the Progressive Conservative government of having the intelligence agency use its mole to discredit the ruling party’s political opponent.

The previous year, before the Sun’s exposé, and behind closed doors, the inspector general warned in a 1993 report to the minister that “the mere fact that a CSIS source is actively involved in a candidate’s election campaign . . . might ‘generate public controversy’ if it became public knowledge.”

In late 1994, the Security Intelligence Review Committee released its own review of the Bristow affair. SIRC found that Bristow was “overzealous” and did not always act appropriately but ultimately determined that he deserved “our thanks” for the valuable intelligence he provided on racist groups. The committee was dismissive of the notion that CSIS had been used as a partisan tool.

Reform Party responds with outrage

“Today’s SIRC report on the Bristow affair highlights the inadequacies of checks and balances on CSIS,” said Manning in the House of Commons on December 15, 1994. “It is also clear that the mechanisms for monitoring the activities of CSIS are ineffectual. They are open to political manipulation by virtue of the patronage appointments to the Security Intelligence Review Committee.”

When contacted by Briarpatch, a spokesperson for Manning said that “he doesn’t recall taking a position on the Security Intelligence Review Committee and … he’s not in a position to comment on it today.”

SIRC’s report also criticized journalists for their coverage of the Bristow affair, singling out the CBC for a report claiming that CSIS spied on postal workers, asserting the claim was “a terrible slur” against the service and not based in fact.

The CBC retracted the story. In 2002, however, Globe and Mail journalist Andrew Mitrovica raised new questions about CSIS’ spying on the postal system when he published Covert Entry, a book based on the revelations of John Farrell, a disgruntled former CSIS operative turned whistleblower.

Farrell provided details on being hired by CSIS to intercept people’s mail after working for Canada Post to spy on postal workers and their union. He also revealed to Mitrovica that intercepting people’s mail was part of an off-the-books CSIS program. He said he was paid through Canada Post and front companies.

Although the Security Intelligence Review Committee has access to almost all CSIS records, it would be oblivious to these alleged activities if it did not pursue rigorous investigations beyond reading the version of events presented to them by CSIS.

Farrell told Mitrovica that SIRC lacks the understanding of the culture and operations of CSIS necessary to provide effective oversight: “SIRC doesn’t know shit.”

In his book, Mitrovica paints a grim picture of the Security Intelligence Review Committee as uninterested in challenging the CSIS version of events. Farrell’s account, Mitrovica wrote, “lays bare the naïveté and ineptness of SIRC and its leaders, who still cling to the belief that since its tiny cadre of investigators enjoy access to the service’s files, they know precisely what’s going on at CSIS.”

Today, Hameed is less scathing than Mitrovica in his assessment of the Security Intelligence Review Committee’s ability to provide effective oversight of CSIS. But he also questions the committee’s effectiveness.

“SIRC is a complaints-driven process, with many part-time members who are generally overworked in their ability to investigate public-interest-type issues,” said Hameed. “I think it is asking a tremendous amount of an institution that is already beleaguered by all sort of problems.”

While the Security Intelligence Review Committee has much stronger powers to compel evidence from CSIS than the courts, Hameed says that SIRC lacks the courts’ power to force changes on CSIS. Without the adversarial nature that is found in the courts, he isn’t convinced that SIRC is rigorously testing the agency’s account of its activities.

“We don’t really know the extent to which SIRC is pushing the envelope on some of these criticisms,” says Hameed. “Do they even necessarily ask the more probing questions?”

He notes that the Security Intelligence Review Committee can have a normalizing effect on CSIS, giving legitimacy to the agency rather than pushing for reform and restrictions on the group’s intrusive powers. “It has the potential to act as a rubber stamp on national security claims.”

Oversight alone, however, may not be enough, Hameed suggests. CSIS may simply be too powerful an entity for oversight to be effective. In the absence of any method for curtailing CSIS’ powers, there is a “need to greatly enhance the powers of SIRC.”

“But in the end that is not really my opinion,” he explains, “because I would say that we should only be using the oversight mechanisms that are put in place as a stopgap to what I think should be done, which is seriously curtailing the role of the service.”