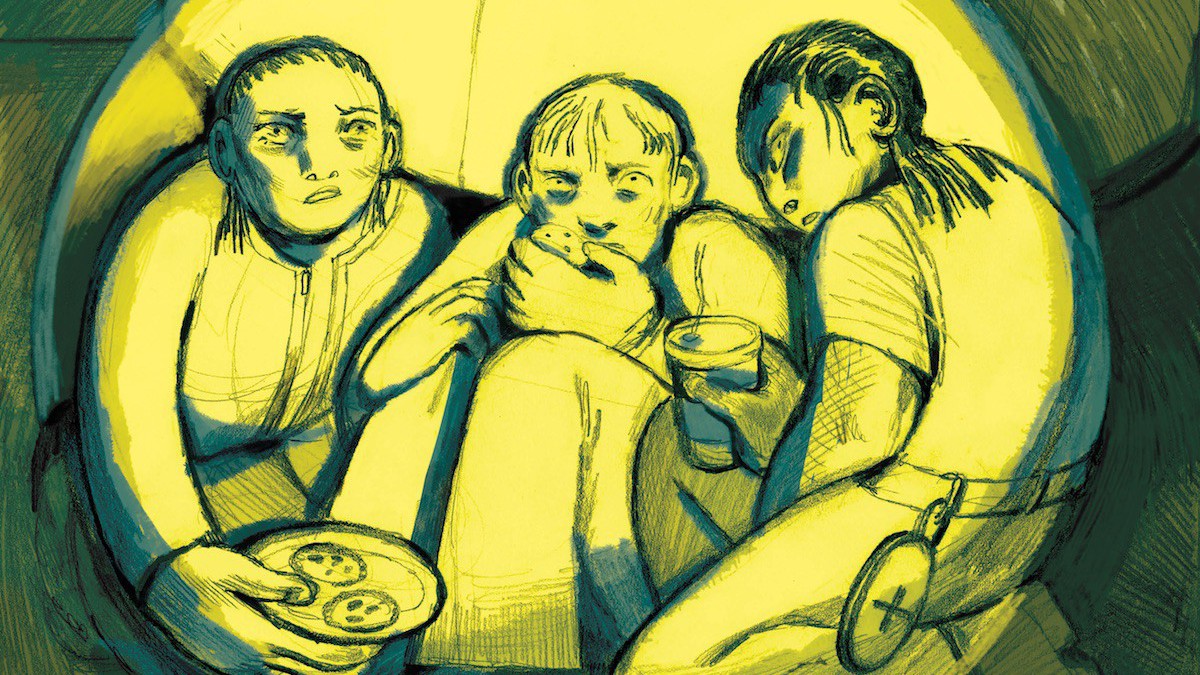

On a sunny Friday afternoon in March, outside the ground-floor office window at the shelter where I work, a man stumbles sideways into the glass and slides down to the sidewalk. My co-worker, Charles, and I go outside with naloxone, chocolate chip cookies, and a cup of coffee. The man tells us his name is Alan. We ask what substances he used this morning and evaluate him for risk of overdose. A bottle of pills spills on the sidewalk and he picks them up, one by one. We ask if we can walk him down the street to the safer injection site. He refuses.

The cops pull up behind us and wave Charles over. They explain that they were called because Alan was walking through traffic. Charles tells them that they can leave and we’ll call if we need them. We sit outside with Alan, eating cookies and talking about the weather, the upcoming long weekend. We ask if he’ll go to the safer injection site now. With more familiarity between us, he agrees to go if we’ll walk him there. In the lobby, I introduce Alan to the reception staff and they welcome him in.

In January 2021, CTV News published an article titled “Montreal homeless shelter lays off front-line workers, hires security guards.” The article described how Accueil Bonneau, one of the city’s largest service providers for people who are unhoused, had reduced their front-line staff by 17 per cent and hired security guards from a private company. Although the article presented it as an isolated incident, it is part of a city-wide move over the last year toward increasing the presence of security guards within front-line organizations, under the guise that their presence is necessary to enforce the hygiene measures that reduce the spread of COVID-19.

When the police showed up, if they had waved over security staff, what would have happened? At the end of the afternoon, would Alan have ended up in jail – or worse – instead of in a space equipped to care for him in case of an overdose?

The presence of security guards marks a change in front-line work and social service work more broadly, characterized by two key elements. The first is a shift in focus from care toward control. The second is an increase in police presence in and around front-line services, because, as service users will explain, security guards often call 911. These shifts have been visible to me during my own time working in the Montreal shelter system.

The integration of security guards into front-line services must be understood within the fraught history of social work. Throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, social work was dominated by efforts to assert control over the poor and those otherwise not contributing sufficiently to capitalist production. In the late 1800s, Canadian politicians began mimicking England’s system, setting up government-run poorhouses or workhouses where poor people laboured in exchange for shelter, meagre food, and basic clothing. The practice caught on across Ontario, Quebec, and the Maritimes, and in 1903 Ontario even passed legislation that required every county to have a poorhouse. These institutions upheld the idea that the “deserving” poor could be saved or redeemed through work.

When the psychiatric deinstitutionalization movement gained ground in the 1950s and 1960s, services began to shift toward a focus on relationships. This flipped the narrative, positioning individuals as the experts on their own experiences and valuing a sense of belonging, community, social integration, and supportive relationships. Consequently, priority was placed on building a therapeutic relationship, and inequalities like poverty became understood as structural issues rather than as individual failures.

“Guards are everywhere, everywhere, everywhere”

At Grand Quai, the day shelter run by Accueil Bonneau in Old Montreal, the walkway leading up to the building is lined by no fewer than five security guards. “It’s like that everywhere now,” Simon, who has lived on the streets for the past two years, tells me. (As with all the service users and front-line staff I spoke to, I chose to omit Simon’s last name to protect his privacy.)

“Like there’s guards in all the shelters?” I ask him. “No, like everywhere I go right now. Guards are everywhere, everywhere, everywhere,” he replies.

It’s difficult to reconcile Accueil Bonneau’s securitized exterior with the “values” section of their website, where they write, “Our warm hospitality is unconditional.”

Gregory, who has accessed Accueil Bonneau services for over five years, has watched the change happen before his eyes. Telling me how it was before the Grand Quai was dominated by security guards, he recalls, “We would say hi, things like that. We were able to socialize here.”

Stefan, who has been unhoused for the past 10 years, tells me, “I don’t like coming here. I feel like a nobody.”

Carolyne Grimard, a social work professor at the Université de Montréal, says the increase in security guards marks “a crisis of care.” By replacing front-line workers, organizations are “putting security ahead of social intervention [and] not recognizing the importance of relationships,” she adds. Research shows that relationships between social workers and the people they support are necessary for cultivating a sense of community and positive changes in service users’ lives. Without a focus on supportive relationships, services play a drastically different role in the lives of service users.

Stefan, who has been unhoused for the past 10 years, tells me, “I don’t like coming here. I feel like a nobody.” Stefan says he comes to Grand Quai mostly for the internet and to have somewhere to go when the weather is bad. He doesn’t come for social connection or support.

For someone to “feel like a nobody” in the places created to offer support means that these spaces are not fulfilling their purpose. In the same way that jails are used simply to warehouse people who are deemed difficult or dangerous, community organizations devoid of social support become a way to keep unhoused people controlled and out of public sight.

As Grimard says, “It’s about the image it sends. It sends the image that people who are homeless are too complicated, take too much time and resources – that we cannot do anything [for them], but we can control them.”

“Two separate worlds”

Front-line workers who are now forced to work alongside security guards – rather than other front-line staff – are also facing challenges. I spoke with Chloe, who works 12-hour night shifts in a Montreal shelter alongside security guards. Her shelter staffs one front-line worker and one security guard per shift; they work collaboratively on the floor. Talking about the challenges of this set-up, Chloe tells me, “They [security guards] don’t have the same training. So sometimes they find our [front-line workers’] decisions too soft, or too laissez-faire.”

What Chloe points to is the reality that security guards are neither prepared nor trained to respond to complex, messy, human-centred situations with anything besides force. If security guards have any role here – and that is a big if – it should be solely to enforce COVID-related hygiene precautions and building-related safety. But working at a shelter that employed security guards, I often saw a conflation of roles. Security staff frequently involved themselves in interventions or, as Chloe notes, they questioned the judgment of front-line staff when service users were not immediately asked to leave after failing to adhere to rules. Security guards, as a profession, work to protect the people who hire them and those people’s property. They are, as Grimard explains, “two separate worlds: security and social work.”

Service users feel this contradiction, too. As Simon explains, “They [Acceuil Bonneau] hired them too fast. They weren’t prepared for these spaces. Really too fast.” Complicating this is the reality that, as Chloe notes, “Often people follow security guards’ [orders] more because it’s like a police figure […] without being exactly a police figure. […] It’s more intimidating to have security guards than front-line staff.” Chloe’s comment also begs the question of whether front-line staff themselves defer to security guards’ orders, whether or not they realize that they’re doing so.

Security guards are neither prepared nor trained to respond to complex, messy, human-centred situations with anything besides force.

It would be easy to read these comments as referring to a few problematic security guards, simply unprepared for their contracts within the shelter system. Rather, it’s necessary to understand this as a systemic issue: security guards, as professionals, exist to maintain control over a space.

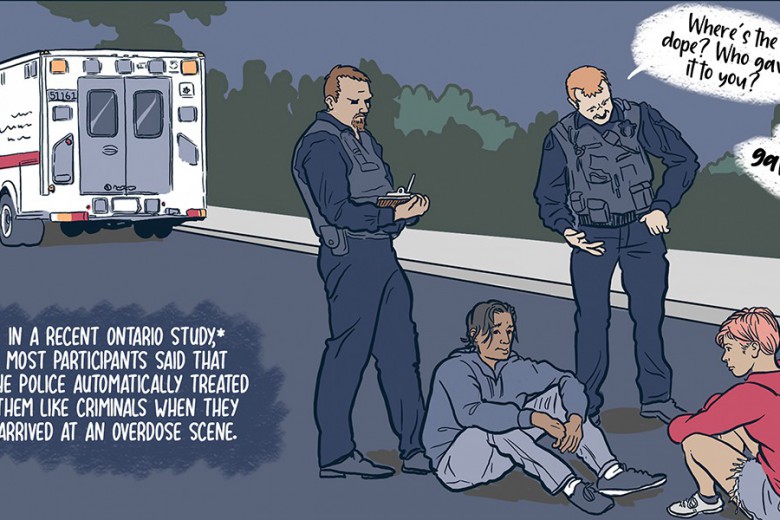

As service users, Simon and Stefan speak openly about the way security guards insert themselves in interventions. “Before you got here, this morning, there was a fight,” Stefan tells me. “The front-line workers were there, then security, who called the police. The guy was taken to jail. I don’t like that.”

I ask again to make sure I’m hearing correctly: “So when there’s a fight, who usually calls the police?”

“The majority of the time, it’s the security guards,” Simon confirms.

Police are already statistically over-involved in the lives of people who are unhoused or street-involved. If security guards increase the possibility that service users will come into contact with police, services become increasingly unsafe for marginalized people to access.

Montreal, like much of Canada, is in the midst of an overdose crisis: in the last two years overdose deaths more than doubled, from 28 deaths in 2019 to 64 deaths in 2020. If people are kicked out of front-line service centres – especially those that work with people who use substances – it puts substance users at risk of overdosing out of sight of people who might be able to facilitate medical care.

In the same way that jails are used simply to warehouse people who are deemed difficult or dangerous, community organizations devoid of social support become a way to keep unhoused people controlled and out of public sight.

Simon emphasizes how quickly security guards remove people who are deemed to be disorderly or disruptive. “And you can’t argue with them. They just kick you out and you’re on the street again.”

When he says this, I think, of course, of Alan. If he had stumbled against the window of Grand Quai instead, his demeanour would have alerted security staff, who would likely have prevented him from entering the building. When the police showed up, if they had waved over security staff, what would have happened? At the end of the afternoon, would Alan have ended up in jail – or worse – instead of in a space equipped to care for him in case of an overdose?

On April 12, 2021, the Tribunal administratif du travail ruled that Accueil Bonneau’s abrupt dismissal of front-line staff was illegal because it violated their collective agreement. Consequently, front-line staff will be offered back their positions. This ruling, however, does not mean there will be a reduction in security guards at Accueil Bonneau, nor does it speak to a change in approach. In all likelihood, when front-line staff rejoin the workplace, they will bump up against some of the same issues that Chloe talked about.

Of course, the people most impacted by this ruling – and by all decisions made about services – are the people who use the shelter system. Decisions about staffing directly impact their lives in a real and tangible way. Front-line social services are not a final solution to systemic inequalities and should never be framed as such. However, while we work to end poverty, racism, and the criminalization of drug use, these services can still have a profound impact on people’s lives. People accessing and using these services deserve to be in genuinely safe, welcoming environments that are focused on building supportive relationships and cultivating a sense of belonging. Organizations must not forget their mandates, nor the lives of the people they aim to serve.

Accueil Bonneau did not respond to requests for comment.