We Interrupt This Program is a hopeful title for a timely book.

Focusing on the past 10 years, authors Miranda Brady and John Kelly examine how Indigenous media-makers of various forms are disrupting the neocolonial Canadian media terrain to assert Indigenous priorities, cultures, and aesthetics. Both authors are professors at Carleton University; Brady is a settler who studies Indigenous identities and media; Kelly is Haida from Skidegate, and worked in journalism prior to academia.

The authors chose to look primarily at interventions within dominant (non-Indigenous) media spaces, particularly established institutional frameworks. One perspective they present – referencing Taiaiake Alfred, Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, and Glen Coulthard – argues that Indigenous priorities of reasserting sovereignty and nationhood are incompatible with working within settler-controlled institutions. But the authors explain that they’re interested in interventions that combine acceptance with refusal, and tactics of media-making that “may not lead to a radical transformation […but] can elicit results.”

Most of the chapters centre around case studies. The first two cases, of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) and IsumaTV, discuss residential school testimonies, methods of documentation, and archives. The authors contrast the short “wrongdoing-focused” public testimonies of the TRC with IsumaTV’s hour-plus online recordings of Inuit residential school survivors. In the latter, testifiers were encouraged to discuss in depth the impacts of the schools on collective life. In contrast, the TRC testimonies had strict time limits – causing one commissioner to remark, “We’re starting to pick up the habits of our white brothers.” The IsumaTV testimonies were an external method for Inuit people to assert their needs within the framework of the TRC, and helped get an Inuit sub-commission in the TRC. These chapters also discuss the uncertain futures of the archives, in part due to challenges with funding.

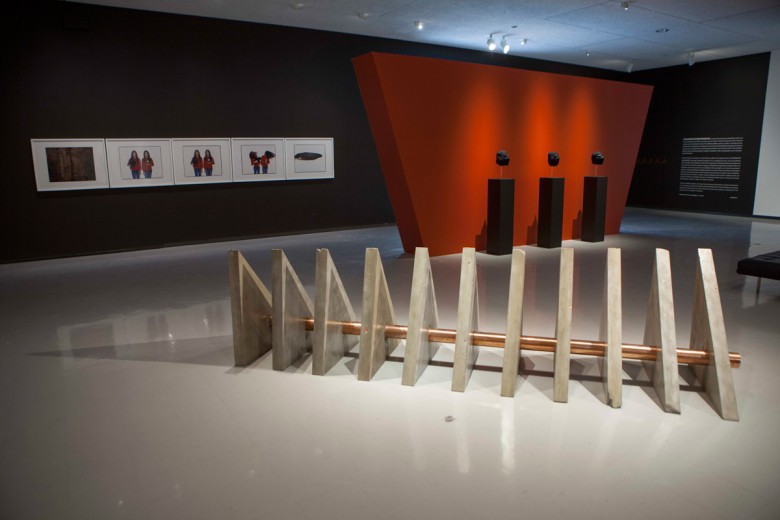

The third chapter highlights three Indigenous artists who are challenging non-Native representations of Indigenous peoples: Dana Claxton, Jackson 2bears, and Kent Monkman. Their work acts to remediate existing media norms and historical art, exposing the mechanics behind settlers’ stereotypical representations of Indigenous peoples.

The fourth chapter focuses on the imagineNATIVE Film & Media Arts Festival in Toronto and filmmakers Jeff Barnaby, Terril Calder, and Shane Belcourt. The festival’s success is attributed to its ability to build community and supportive, inclusive networks, and to provide essential exposure for diverse media-makers. The festival helps Indigenous filmmakers confront their main barriers within the film industry: financing, cultural misconceptions, access to industry partners and networks, and distribution.

The final chapter looks at mainstream journalism, via the perspective of Duncan McCue, a long-time CBC reporter and a journalism professor at the University of British Columbia. McCue discusses the under- and misrepresentation of Indigenous peoples in mainstream journalism, and the need to move beyond reporting that evokes pity, or pits Indigenous people against settlers. For journalists covering Indigenous issues, McCue advises, “If you could boil down my whole course down to one thing, it’s to act with respect.”

The book doesn’t explore social media, though it was conceived and grew rapidly in the decade this book covers. Without it, the book has less sense of the real-time implications of Indigenous media-making, including its role in facilitating social movements like Idle No More and #NoDAPL.

As the authors note, Indigenous peoples’ relationships to media have evolved as “colonization happened synchronously with the development of a number of media technologies, including photography and motion pictures.” The recent and dramatic collective shift in our relationships to media has occurred alongside a significant shift in Indigenous relations with settler society – during an age of so-called “reconciliation” and increased visibility of Indigenous perspectives, including dissent. The book provides an analytical perspective to help readers reflect on what types of new interruptions may be brewing – or to plan the interventions themselves.