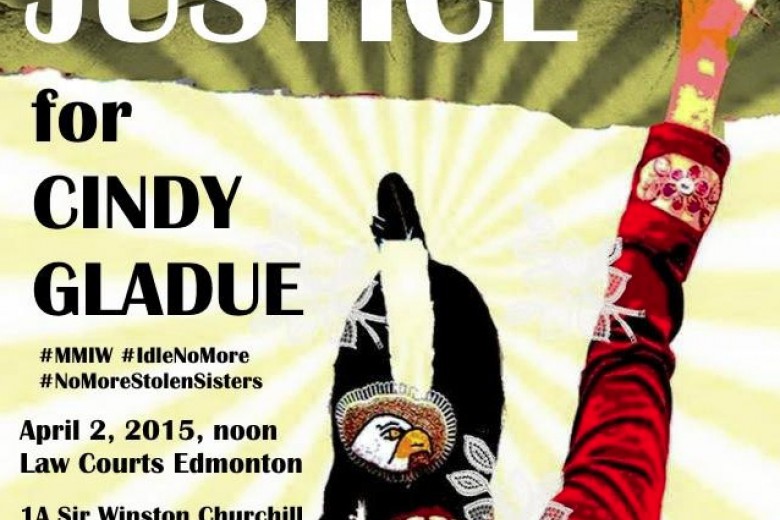

When the Truth and Reconciliation Commission wrapped up its six-year investigation into the horrors of Canada’s Indian residential school system this spring, it released a nearly 400-page summary of its findings and 94 recommendations for improving relations with Indigenous peoples.

Among the recommendations – which call for everything from restoring Indigenous languages to demanding an apology from the Pope – was a call for Canada to adopt and implement the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP).

For many, the adoption of the declaration represents a key step toward genuine reconciliation between Canada and Indigenous peoples.

The 2014 UNDRIP implementation guide for parliamentarians highlights “toxic contamination of Indigenous peoples’ lands” among the systemic forms of oppression governments are obligated to address under the declaration. Indigenous leaders in northern Manitoba would certainly welcome this measure.

According to federal government figures, the bulk of Manitoba’s most highly contaminated sites are in First Nations communities, and people in these areas are concerned it’s making them sick.

The Treasury Board of Canada keeps a database of contaminated sites across Canada called the Contaminated Sites Inventory. According to the inventory, of the 77 “high priority” contaminated sites in Manitoba, 70 are situated in First Nations communities.

Sites are categorized as “high priority for action,” “medium priority,” “low priority,” “insufficient information,” “not a priority for action,” or as a “site not yet classified.”

Fifty-nine of those 70 sites are the responsibility of the federal department of Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development. The other 11 sites fall under the functioning of Health Canada and Environment Canada.

A total of 37 sites are listed as “closed,” meaning no further action is required; however, 33 are still listed as “active,” which means the sites are confirmed to be contaminated and remedial action is or may be required.

The 77 high-priority sites are merely the ones in which the government knows what has caused the contamination. A further 196 sites in Manitoba are listed as “suspected” or “active” in the inventory. It is unknown how many of these sites are in First Nation communities.

But of those 70 known high-priority sites in Manitoba, two northern First Nation communities – the Shamattawa and Sayisi Dene First Nations – are the most contaminated.

Shamattawa First Nation is in the northeastern corner of the province, some 745 kilometres from Winnipeg by air. In a community facing numerous hardships, including a string of youth suicides in January and March of this year, there are contaminated land areas with over 11,000 tonnes of petroleum hydrocarbons (PHCs) in the groundwater and soil.

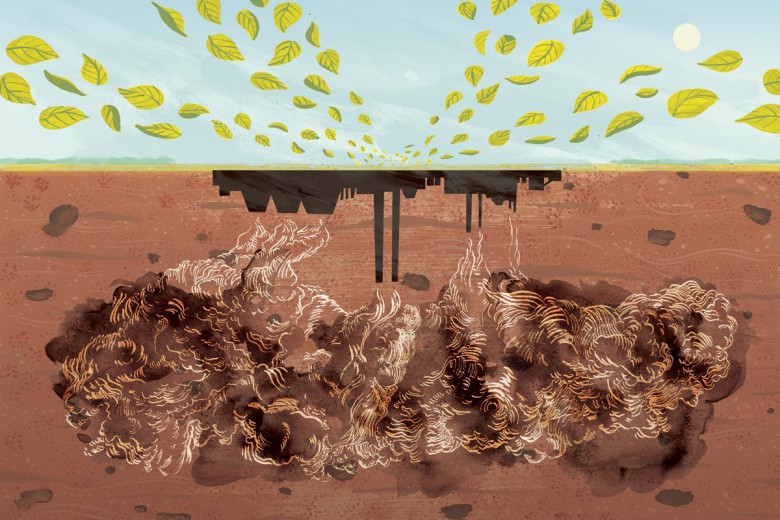

Petroleum hydrocarbons are chemical compounds that are found in oil, gas, diesel, and other petroleum-based fuels. Some of these compounds are believed to be carcinogenic or to affect the central nervous system in humans.

PHCs are among the most common soil contaminants in Canada and are often caused by fuel spills.

The federal government is taking steps to clean up these sites through a process called remediation. There are three sites in Shamattawa First Nation, which range from step four to step seven in the 10-step management process (the federal government uses a 10-step process for addressing a contaminated site).

According to the Contaminated Sites Inventory, there are approximately 138 people living within a one-kilometre radius of the contaminated sites in Shamattawa First Nation, with 1,094 people living within a five-kilometre radius, and 1,205 people living within 10-50 kilometres.

Chief Jeff Napoakesik of Shamattawa First Nation says some remediation projects have been underway since 2008, but he knows there are other areas in the community that still need to be cleaned up. Napoakesik isn’t sure exactly how the federal government is cleaning up the sites. In one instance, he said large pumps seemed to be forcing air into the ground.

“We think that’s not proper,” he says. “In order to do a proper cleanup you have to take out the soil, the contaminated soil.”

Napoakesik also says the federal government is only cleaning up the most recent spills, but there have been many spills in the past.

For instance, the RCMP facilities alone have had several fuel spills over the years, while other spills have caused the community’s school to close and contaminated their sewage system. And, Napoakesik adds, “there’s probably still traces of fuel in there.”

Napoakesik also recalls an old nursing station that was powered by a diesel generator, which resulted in multiple fuel spills. “Nobody has properly investigated how or what the extent of the contamination is,” he says.

When asked whether he thinks people have ever been made sick because of contaminants, Napoakesik says he is positive that community members have been in direct physical contact with the contaminated soil on their lands. “People had died of cancer,” he says. “Those people were nearby, a couple hundred feet from the sites, contaminated sites.”

Northwest of Shamattawa First Nation, Sayisi Dene First Nation is listed as the second highest priority contaminated area in the province; it is likewise at step seven of the federal 10-step process.

Two sites in the Sayisi Dene First Nation are each contaminated with 3,205 to 5,310 tonnes of PHCs, and a third site is polluted with polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), another toxic, petroleum-based substance.

Sayisi Dene First Nation is not connected to Manitoba’s power grid, so diesel generators provide electricity for some buildings. The diesel for the community is stored in a series of large containers called tank farms.

Aboriginal Affairs says a former storage tank that provided fuel to the school was the source of one of Sayisi Dene’s contaminated sites. The department says the spill resulted from a faulty pipe and improper handling during storage tank refilling over the years.

Another leaky tank farm – which provided fuel for a band building – was the source of the other contaminated site.

According to the Treasury Board inventory, as many as 184 people live within a one-kilometre radius of the two contaminated sites in Sayisi Dene First Nation, and a further 319 people within 5-50 kilometres.

The elected leader of Sayisi Dene says soil remediation projects have been underway in the community. “The project is in its final stages, as far as I can recall,” says Chief Ernie Bussidor. “I think the last step is to turn the contaminated sites into a waste disposal site and that’s supposed to happen this fall.”

Bussidor says he continues to be concerned, though, about the long-term effects of contaminants in the soil. “We can’t just get up and move anymore; this is probably the oldest permanent settlement of our band in history.”

With a long and disastrous history of forced relocation by the Canadian state, the people of Sayisi Dene have only been living in their current location since 1973. For the first 10 years there, the community lived without electricity.

According to Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada, remediation work has been underway since 2010. More than 7,397 cubic metres of PHC-impacted soil was excavated from both sites and hauled to the community landfarm for treatment. Another 18 cubic metres of soil was removed in 2011. Landfarming involves a process of tilling the soil in order to break down contaminants. Once landfarming is complete, the soil will be tested. If it’s found that the levels of contaminates are safe, the landfarm will be converted into a landfill.

SAYISI DENE FIRST NATIONIn 1956 the governments of Canada and Manitoba conspired to relocate the Sayisi Dene First Nation from their traditional lands near Duck Lake in the far north to the shores of Hudson Bay. The results were catastrophic. There was no access to fresh water and the nation’s capacity for traditional hunting and gathering was shattered, with the people relegated to living in shacks next to the Churchill graveyard. Children foraged for food in the dump and one third of the relocated population had died by 1973, when the Sayisi Dene were able to move back to their traditional lands, this time near Tadoule Lake. Today, Sayisi Dene First Nation is home to several thousand tonnes of leaked, toxic petroleum hydrocarbons (PHCs) and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) caused by the diesel tank farms that serve community generators.

However, Sayisi Dene faced years of exposure prior to remediation. “We lost a lot of Elders in the last 30 years, but it’s hard to say whether it was attributed to any kind of contaminants,” says Bussidor. He also notes that there was an old hydroelectricity generating plant that was removed from their community in the 1990s because of leaking transformers, which he had raised as an issue with the plant supervisor at the time.

“They then smashed up the concrete patch of leaking chemicals when they took the plant down,” says Bussidor. “A lot of Elders who lived around the perimeter of the plant passed away in a relatively short time. I was told not to worry about the leaking transformers as they contained only ‘honey oil.’”

Like Shamattawa, the community of Sayisi Dene has dealt with its fair share of fuel spills. “There were diesel spills everywhere in the community in the first 20 years that we lived here,” says Bussidor.

As for addressing all other high-priority contaminated sites that fall under their jurisdiction, the department said only 19 sites have been identified as requiring remediation activities for the fiscal year of 2015-2016.

The communities of Nisichawayasihk Cree Nation, Bunibonibee Cree Nation, and Lake St. Martin First Nation have also been found to have large amounts of contaminants in their lands and waters, including metals, metalloids, and organometallics in their groundwater. The highest step completed for these communities to date is step 4, which means the government is in process of classifying the contaminated sites.

The Manitoba Keewatinowi Okimakanak, a political advocacy organization representing 30 First Nation communities in the far north, would like to see a timely cleanup of these contaminated sites. They are also concerned about the contaminants left behind by the numerous abandoned mineral mines in the region, as well as by Manitoba Hydro operations.

The process for cleanup in northern communities has been slow, and some people question whether remediation activities are being done properly and whether all contaminants are actually being removed.

If ever adopted by Canada, the UNDRIP would compel the government – at least on paper – to uphold Indigenous peoples’ rights to their lands and territories, and to protect them from toxic contamination.

But with a further 196 sites still waiting to simply be assessed, it seems Indigenous communities in Manitoba will be dealing with this toxic problem for years to come.

This investigative feature is a collaboration co-published with Ricochet Media.