Across Canada, long-term care homes have become the epicentre of deaths during the COVID-19 pandemic. In Saskatchewan, 33 per cent of all COVID deaths happened in long-term care facilities, and more than half of those occurred in private facilities. Although the numbers are devastating, the subject of long-term care loomed large in the provincial consciousness long before the pandemic started.

Some of the homes that have had the deadliest outbreaks – Santa Maria, Extendicare Parkside, and Regina Pioneer Village – have previously made headlines for violence against residents, infrastructure that is literally crumbling, and death due to neglect. Less than six weeks before the province enacted a state of emergency due to COVID-19, it issued layoff notices to workers at Pioneer Village, closing beds and moving some residents to private care homes. For years, the health region has been delivering reports of public and private homes that are understaffed, overcrowded, dilapidated, and lacking appropriate infection-control protocols, some of which – like the Luther Special Care Home in Saskatoon – would become the sites of deadly outbreaks.

Beverley Hartnell, whose father, Bernard, was one of 13 people to die in a COVID-19 outbreak at Regina’s Santa Maria Senior Citizens Home, says she was both “surprised and not surprised” when the pandemic struck the home, primarily because there were simply not enough workers, even in the best of times. “I always wished there was more staff,” she recalls. “I never thought they had an adequate staffing number because there was always somebody crying in the corner or something. There needs to be more staff and the staff need to be paid well because it’s a very, very challenging yet important job.” When asked whether she thinks the workers in the care home where her father lived and died had all the resources needed to meet the challenges of the pandemic, Hartnell says, “Oh God, no. Obviously, we see that now.”

“I never thought they had an adequate staffing number because there was always somebody crying in the corner or something. There needs to be more staff and the staff need to be paid well because it’s a very, very challenging yet important job.”

The problem of understaffing and under-resourcing in long-term care isn’t a new one – 20 years ago, Saskatchewan workers unionized with CUPE, including those working in long-term care, went on strike for six days in protest of “crushing” workloads. And although they won that particular battle, they lost – and continue to lose – the war. Over the past decade, the provincial government has continued to remove staffing requirements, making working conditions worse and eroding the quality of care. Workers in these homes also face alarming amounts of violence. According to Pat Armstrong, a Canadian sociologist who has been researching long-term care in Canada for decades, staff in long-term care homes are more likely than police officers to be injured on the job and they are also more likely to be on sick leave.

Hartnell’s story is devastating, as are the conditions faced by many workers in long-term care. Still, Saskatchewan has fared better than the Canadian average, where people living in long-term care homes account for 80 per cent of COVID deaths. This is, in part, because Saskatchewan has managed to retain a relatively robust system of public care homes: three quarters of long-term care facilities in the province are publicly owned, the highest proportion outside of Quebec, Newfoundland and Labrador, and the Territories. There are only five private, for-profit special care homes (sometimes called “nursing homes”) operating in the province, all of them owned by Extendicare. Dr. Susan Braedley, a Carleton professor who co-authored a 2019 report on long-term care in Saskatchewan for CUPE, says that this is, at least in part, for the same reason that the province has managed to maintain more Crown corporations than many other provinces: our sparse, widely dispersed population makes it unappealing for those who would seek to profit off long-term care. “Saskatchewan is not very enticing to some of the big providers,” Braedley says. “It’s hard to make money when the population is so scattered, so small.”

So, while Extendicare operates in the province, long-term care privatization in Saskatchewan tends to be more insidious than the massive for-profit homes in Ontario and Quebec. It takes the form of public-private partnerships (P3s): The Meadows in Swift Current, which was built in conjunction with Plenary Health Swift Current Ltd. from 2014 to 2016; the contracting out of certain services, like laundry, food services, and cleaning; or, most substantially, so-called “personal care homes,” which are privately run homes that set their own fees and are given licences and monitored by the Saskatchewan Health Authority (SHA). They are typically – but not always – licensed and operated by people with direct ties to the community in which they operate, including individuals and couples who operate homes with as little as one bed. While the five largest personal care homes have more than 100 beds, the vast majority are far smaller. There are 136 with 10 beds or fewer and more than 200 have 20 beds or fewer. They operate in Saskatchewan’s largest cities and in places as small as Smeaton, a village of 182 located 80 kilometres northeast of Prince Albert.

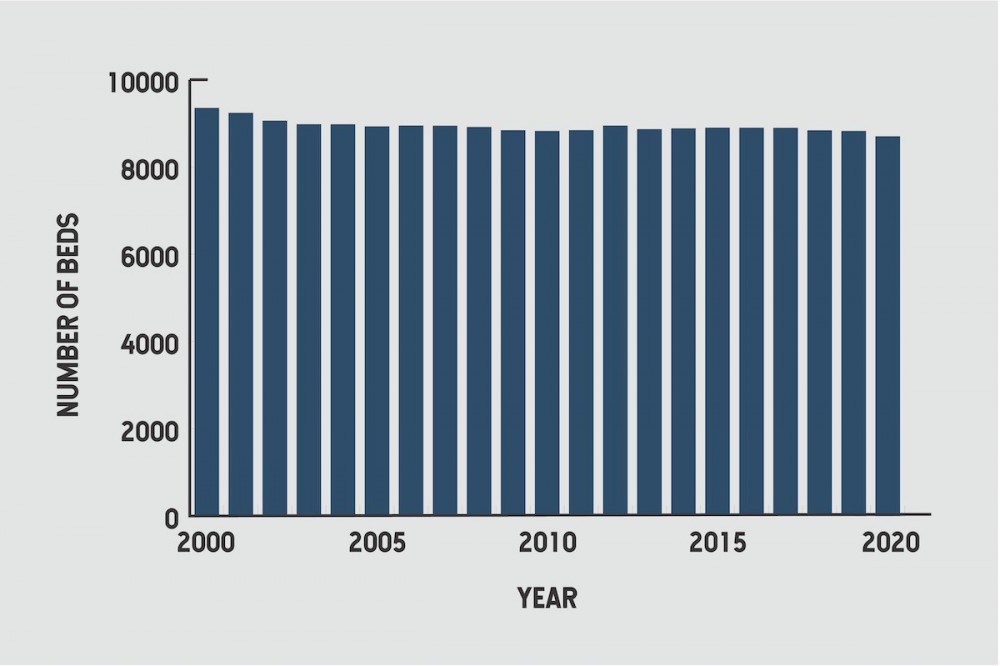

“Personal care homes have been the major initiatives in Saskatchewan, so the support to personal care homes from the government has increased building capacity in that sector,” Braedley says. There’s been a steady increase in the number of beds in personal care homes in the province, even as the number of beds in long-term care overall has fallen. There were 1,464 personal care home beds in 1991. By 2020, that number had more than tripled, to 4,840 beds in 253 homes. By comparison, in 2001, the year CUPE workers went on strike for six days, there were 9,240 beds in long-term care. By 2020, there were 8,704.

Here’s how private personal care homes differ from public long-term care homes. In the former, the monthly expense – which ranges in cost from $1,000 per person per month to more than $4,000 – is typically paid in full by the resident, although the government has been working for more than a decade to subsidize more residents to live in these private homes instead of in public care homes. Residents are also not required to “demonstrate need” to move into a personal care home – this allows people who need more care to access it, even when they don’t meet the stringent requirements that the government has imposed, as the number of available beds in special care homes has declined. Many personal care homes provide far less intensive care than public special care homes, in which nursing oversight of all care is mandatory – but some personal care homes provide level three and four care, right up to palliative care. So while personal care homes are not actually considered to be “long-term care” in the strictest sense of the term, for all intents and purposes, that’s what they are.

Personal care homes are not required to provide a bathroom for every resident, and in fact they are only required to provide one toilet and one sink for every five residents. While all personal care homes are required to have staff on site 24 hours a day, those staff don’t have to be awake at night in homes with 10 or fewer residents. Some have stipulations that they can’t house residents who are at risk for wandering or who can’t manage stairs independently, but for the most part, licensees are responsible for determining the level of care they are willing and able to provide. In some cases, that care is excellent, beyond what even the public special care homes can provide. In others, operators are completely overwhelmed by the demands of the job.

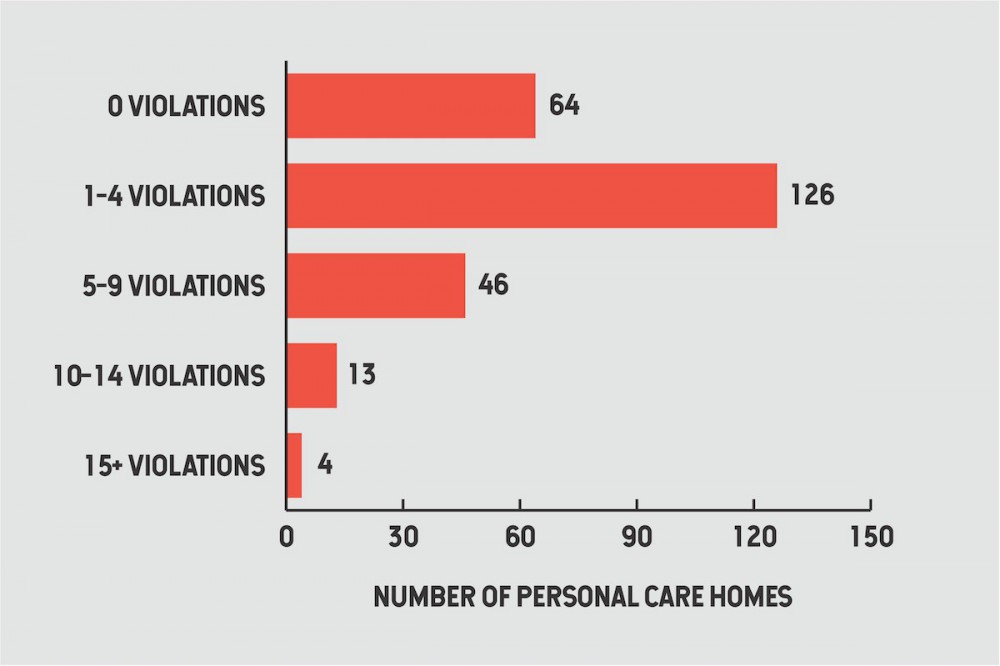

Personal care homes are inspected, on average, once every two years. Of the 253 homes listed on the Government of Saskatchewan Personal Care Home Inspection list, 144 have not been inspected since the pandemic began and 12 have not been inspected since 2018. Many have been found to be in violation of one or more regulations, most often fire safety violations, improper storage and preparation of food, and a failure to administer medications according to the 6 Rs (right resident, right time, right route, right medication, right amount, and right documentation). There were 126 personal care homes with between one and four citations on their last inspection, 46 had between five and nine citations, 13 had between 10 and 14 citations and four homes had more than 15 citations. The worst offenders, Emina and Goran Jelisavac’s 10-bed home in Saskatoon and Nikki Elliott’s six-bed home in Christopher Lake, had 23 and 25 violations, respectively. Five of the homes, including Elliott’s, were flagged for using physical restraints on residents beyond what might reasonably be required to assist the resident in daily living.

While five of the 17 homes charging between $1,000-$1,499 per month – the lowest fees in the province – are among those with 10 or more violations on their last inspection, paying more doesn’t necessarily ensure a home is fully compliant with regulations. Of the 12 homes charging residents $4,000 or more per month for a room, six had five or more violations and one, College Park II in Regina, received nine citations, including failure to administer medication according to the 6 Rs, failure to safely store and prepare food, and for using physical restraints on residents. At their previous inspection, they had received 16 citations. Green Falls Landing, another private care home in Regina that charges upwards of $4,000 per month, also had nine violations, including failing to ensure the “home is operated in a manner that provides safety for the well being of the residents, staff, and visitors of the home” and Hill Top Manor in Weyburn, which charges between $2,800 to $3,499 for a room, had 12 violations at their last inspection, including failure to have basic or standard first aid.

“Personal care homes have been the major initiatives in Saskatchewan, so the support to personal care homes from the government has increased building capacity in that sector,” Braedley says. There’s been a steady increase in the number of beds in personal care homes in the province, even as the number of beds in long-term care overall has fallen.

Quality can vary widely, even within a group of care homes owned by the same licensee. At one Quality Care Home location on Konihowski Road in Saskatoon, there were no violations reported at their August 12, 2019 inspection. Just next door on the exact same day, in another Quality Care Home location, inspectors recorded nine violations. The SHA says that it works with homes that are not in compliance with regulations to “facilitate compliance.” Sometimes this is effective. Cayden’s Premier Care Home, a 15-bed facility in Saskatoon, had 18 citations, some of them quite serious, at its 2019 inspection. Two years later, it recorded two. Other homes have not fared as well. Elliott’s has averaged 10 violations per inspection, with the fewest violations when inspections were announced beforehand. The Jelisavacs’ home has averaged 12 violations per inspection.

It’s tempting to dwell on the problems of private facilities and for-profits, but the issues with long-term care don’t end with personal care homes, and indeed, many of the problems of long-term care have been happening in public care homes and in affiliate homes (affiliate homes have a contract with, and receive most of their funding from, the government). Hartnell says that one of the things she hopes people take away from her father’s death is that “government facilities are having a horrible time. The media and the public are looking at for-profit homes, but it’s not just them.” Indeed, prior to the pandemic, it was public and affiliate care homes that were making headlines for their substandard conditions, generally due to understaffing and failing infrastructure. Pioneer Village, Saskatchewan’s largest long-term care home, is one of the most notorious. Braedley’s 2019 report, Crumbling Away, was named so in part because of the conditions of the building, which already needed tens of millions of dollars in infrastructure upgrades, even before a water main break caused tens of thousands of dollars in damage in 2018. It’s also no stranger to outbreaks: it was the site of a Norwalk virus outbreak in 2006 and a bedbug outbreak in 2010.

The provincial NDP under Roy Romanow and later Lorne Calvert began hiking fees for long-term care and shuttering beds in the early 2000s, opening the door for more privatization. The Sask Party accelerated the privatization and marketization of the sector after their election in 2007. In 2009, they released the Patient First Review Commissioner’s Report on the status of health care and health-care infrastructure in Saskatchewan. The report describes an “insatiable appetite for replacement of health care infrastructure” and recommends, as a solution, “alternative funding mechanisms” – privatization, by any other name. In 2011, they eliminated the Housing and Special-care Homes Regulations instituted by the Calvert government in 2004, which had set a requirement for a minimum of two hours of care per patient, per day, and replaced them with nothing. The number of care home beds has also fallen, and an increasing number of buildings are falling into states of disrepair that will cost millions to fix. Braedley says that these are deliberate choices, intended to undermine trust in the long-term care system. “This is a sector that many governments have doomed to fail. I mean, this is about getting out of this business [of long-term care], and one of the ways to do that is to erode it, so that there’s no longer public confidence. That’s a strategy. That’s a plan, not an accident.”

Meanwhile, public money is making its way into the private sector. Extendicare received $40,071,000 from the SHA in 2019-20, including a payment of $112,229 “for the provision of goods and services, including office supplies, communications, contracts and equipment,” as well as a transfer of 39,956,108. And licensees of at least 11 personal care homes received transfers from the SHA in 2019-20 for services totalling more than $9 million. Goran Jelisavac alone received $106,698 for personal services from the SHA in 2020. Affiliate homes – private, not-for-profit residences like Santa Maria in Regina, Providence Place in Moose Jaw, and LutherCare Communities in Saskatoon – received $215,602,000 from the SHA last year.

“This is a sector that many governments have doomed to fail. I mean, this is about getting out of this business [of long-term care], and one of the ways to do that is to erode it, so that there’s no longer public confidence. That’s a strategy. That’s a plan, not an accident.”

So, what is to be done? The answer is complicated. Capital investment for infrastructure and a four-hour minimum of care per resident, per day are necessities, but that’s not the whole solution. The problems of long-term care go deeper than a lack of money and staff. We need to think about why that money and those staff are able to go missing from the equation in the first place, and that’s largely a cultural problem, not a problem of any one government.

“In North America we see nursing homes as a last and worst option,” says sociologist Pat Armstrong. She says we see them “as an indicator of failure. You failed to look after yourself. Your family failed to look after you. The doctors failed to fix you. Rather than seeing this as one stage in our lives that is still worth living.” Viewed in this way – as a symptom of personal, familial, and medical failure – it is unsurprising and even natural that many people’s experience of long-term care, often the final experience of their lives, would verge on being punitive. It also explains the abysmal conditions that many care workers, especially those who are not unionized, experience on the job. They are, according to this belief system, doing work that anyone could do, but no one wants to do so.

But the work that staff in long-term care homes do is highly specialized. Although it’s true that the rise of the nuclear family has led to outsourcing care work that used to be done in the home, that work has also moved out of the home for medical reasons. People, even those with complex health issues, are living longer than ever before, and by the time an individual moves to a care home, they’re often very frail and medically fragile, requiring far more support than can be provided by their families. Care work has moved out of the home by necessity. “It’s a population with much more complex needs than in the past [and] it’s not being treated as [being] as complicated as it is, even as it’s growing more and more complicated,” Armstrong says.

“It takes a lot of skill to get someone who has dementia and some other complex health issues to eat dinner or get up and get dressed in the morning,” Armstrong continues. “We have to start recognizing that this is skilled labour. And that includes everything you do in the home that is skilled labour, in terms of cleaning, for example, and it’s skilled labour in terms of preparing the food.” Armstrong says one of the major hurdles to accepting that care work is highly skilled and needs to be treated as such is the fact that it’s perceived as “women’s work.” “So much of this is associated with what women do on a daily basis that we think it’s just something that comes naturally to women,” she adds.

“It’s a population with much more complex needs than in the past [and] it’s not being treated as [being] as complicated as it is, even as it’s growing more and more complicated.”

But this isn’t work that just anyone can do, as Quebec found out early in the pandemic when they set out to hire 10,000 people to work in care homes, telling them they would pay for their training and increase wages. “While they certainly did increase the numbers quickly, they also found that a lot of the people took the training and realized ‘this isn’t for me’ or realized that the conditions of work hadn’t been changed significantly,” Armstrong says. Recognizing and appreciating the specialized nature of care work will go a long way toward improving conditions for both workers and residents.

Braedley says that another approach to improving the quality of life for residents and workers beyond simply throwing money at the problem is to change where care homes are located. Right now they exist, both physically and psychologically, on the periphery of society. “Some of the most promising examples of improved care we have are simply where [care homes] were attached to a shopping mall, to recreation centres, to places where everybody in the community goes once a week, and they’re connected,” Braedley says, offering up the possibility of long-term care as something that is central to our society. “If you can push a wheelchair from the long-term care home into the shopping mall, all of a sudden, that nursing home becomes central to the life of the community in a different way. If you can go and grab Grandma and push her down the hallway while your child has a swimming lesson, that changes everything.”

In Saskatchewan, there has been a call for major, systemic reform for years. In May 2013, the Law Reform Commission of Saskatchewan published a report on civil rights in long-term care. They urged a mandatory bill of rights for people living in long-term care and the creation of an independent advocate. The province never acted on it. Nor has the provincial government developed, implemented, and made public a strategy to meet the needs of long-term care residents and to address the factors affecting the quality of long-term care in Saskatchewan, as was recommended in an ombudsman’s report following the death of 74-year-old Margaret Warholm in Santa Maria in 2015.

“If you can push a wheelchair from the long-term care home into the shopping mall, all of a sudden, that nursing home becomes central to the life of the community in a different way. If you can go and grab Grandma and push her down the hallway while your child has a swimming lesson, that changes everything.”

If long-term care reform is to happen, the story we tell ourselves about nursing homes has to change, shifting them from being places where people are perceived to have been banished to die, to places where they are mindfully and lovingly welcomed to live the rest of their lives. Hartnell’s father lived in Santa Maria for four and a half years before his death in January 2021. She says “that was exactly where Dad needed to be.”

There’s been increased attention paid to long-term care over the past year, but Armstrong is worried that once the vaccine is rolled out, “the death rates will go down and then we’ll say ‘well, we don’t have to deal with that anymore.’” It’s not a misplaced fear. The social, cultural, and political shifts that need to occur in the long-term care sector are massive and expensive ones, and societal memories are as short as the government’s purse strings. “What happens in the wake of a scandal is more regulations and primarily regulation of the staff, and more paperwork for the staff, rather than addressing major structural issues, like the staffing levels, like the wages and working conditions,” she says. This means that when the focus turns on long-term care, it almost inevitably means that staff end up spending even more time on paperwork and less time on actual patient care, including social care. But one thing everyone – from those who study long-term care to those whose loved ones have lived and died there – is clear on is that the staff are, with very few exceptions, already doing the best they can with what they have. Armstrong says, “A lot of the change models have talked about resident-focused care, but what we’ve been arguing forever is that you can’t focus on the resident if you don’t have the conditions of work.”